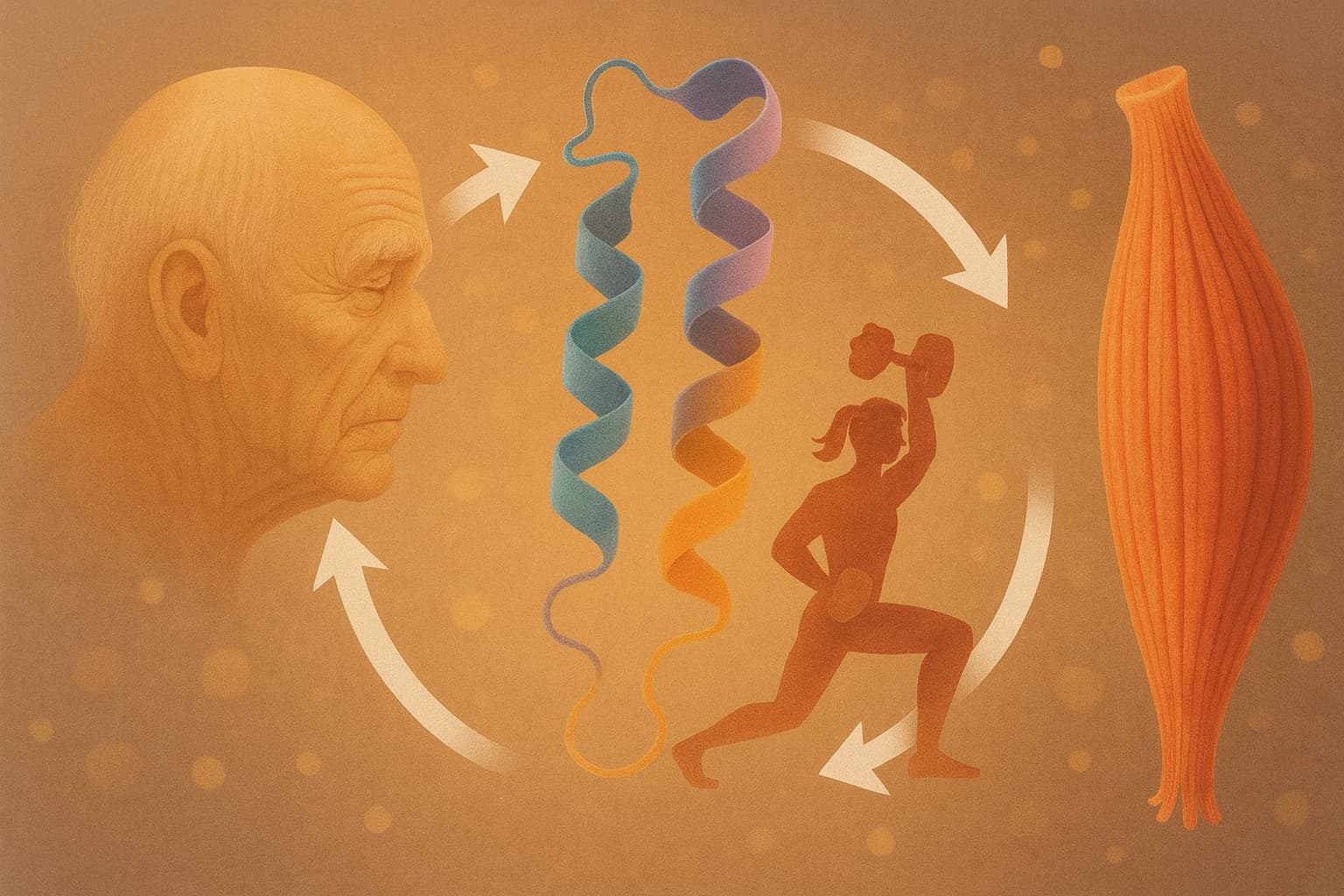

A new comprehensive review in Nutrients (Pérez-Castillo et al., 2025) delivers one of the clearest syntheses to date on why aging muscle becomes harder to maintain, why even lifelong athletes are not fully protected, and which nutrition–exercise strategies have the strongest mechanistic support for preserving muscle function across the lifespan. The paper focuses on “anabolic resistance”—the age-associated reduction in the muscle’s ability to build new protein in response to food and training—and reframes it as a preventable and modifiable hallmark of musculoskeletal aging rather than an unavoidable decline.

The central finding is blunt: most people over 40 experience a “right-shifted” response curve, meaning they need higher doses of anabolic stimuli—protein, essential amino acids, leucine, and training intensity—to achieve the same muscle-building signals that younger adults achieve with less. Stable-isotope tracer studies show that when older adults ingest small or moderate doses of protein, muscle protein synthesis rises less and rises more slowly. Even after resistance exercise, the synthetic response is blunted unless sufficient high-quality protein is consumed.

The review examines whether lifelong exercisers—so-called master athletes—escape this decline. The answer is more nuanced than commonly assumed. Lifelong endurance athletes exhibit superior insulin sensitivity, lower body fat, and better metabolic health than age-matched controls. Yet direct tracer studies show that their muscle protein synthesis response to exercise remains lower than in young athletes, and in some cases is no better than in untrained older adults. Lifelong fitness reduces secondary aging (inactivity, adiposity, poor glucose control), but does not eliminate the intrinsic age-related changes in muscle signaling.

Several modifiable drivers emerge as the most important accelerators of anabolic resistance: episodic inactivity, even for a few days; insulin resistance, which restricts amino acid delivery into muscle; and excess adiposity, which interferes with anabolic signaling pathways. These factors are common, cumulative, and fully amenable to lifestyle intervention.

On the nutritional side, the strongest evidence supports higher daily protein intakes—1.2 to 1.6 g/kg/day for active adults, up to ~2.0 g/kg/day during high training loads or recovery periods. Per-meal targets matter: older muscle requires 30–50 g of high-quality protein delivering at least 2.5–3 g leucine to reliably trigger robust synthesis. Leucine or essential-amino-acid enrichment can rescue sub-optimal meals, though long-term superiority over simply increasing total protein is unproven.

The review highlights EPA/DHA omega-3 fatty acids (~2–3 g/day) as a plausible enhancer of muscle protein synthesis and mitochondrial function, particularly in older women, though results vary across studies. HMB (3 g/day) shows protective effects in situations of immobilization or very high training stress, functioning more as an anti-catabolic buffer than a true anabolic signal.

For healthspan and longevity, the implications are direct. Maintaining muscle mass and strength is one of the strongest predictors of survival, independence, metabolic resilience, and late-life physical capability. This review reinforces a practical formula: combine progressive resistance training, vigilant avoidance of inactivity, optimized protein dosing, and targeted supplements when appropriate. Muscle aging is not inevitable; it is responsive to inputs. The biology of anabolic resistance may shift with age, but the pathway to preserving muscular longevity remains highly actionable.

Open Access Research (review) Paper: Age-Related Anabolic Resistance: Nutritional and Exercise Strategies, and Potential Relevance to Life-Long Exercisers

Note - Conflicts of Interest: Several authors are affiliated with Abbott Nutrition; the review leans heavily into protein supplements, leucine/HMB, and medical nutrition products.

Detailed ChatGPT5.1 Analysis of paper:

Related discussion thread: Are we wrong about the perfect protein intake?