More than a decade ago, scientist Tony Wyss-Coray stitched together the blood vessels of two mice, allowing their blood to intermingle. The results of this gruesome and pioneering experiment facilitated a leap forward in our understanding of longevity: that younger blood can help the memory.

The blood of the younger mouse had a clear impact on the older one, Wyss-Coray said. “We found that there’s less inflammation in the brain [of the older mouse], there’s more stem cell activity, and most importantly, [the older mouse] was doing better in memory tests,” he explained.

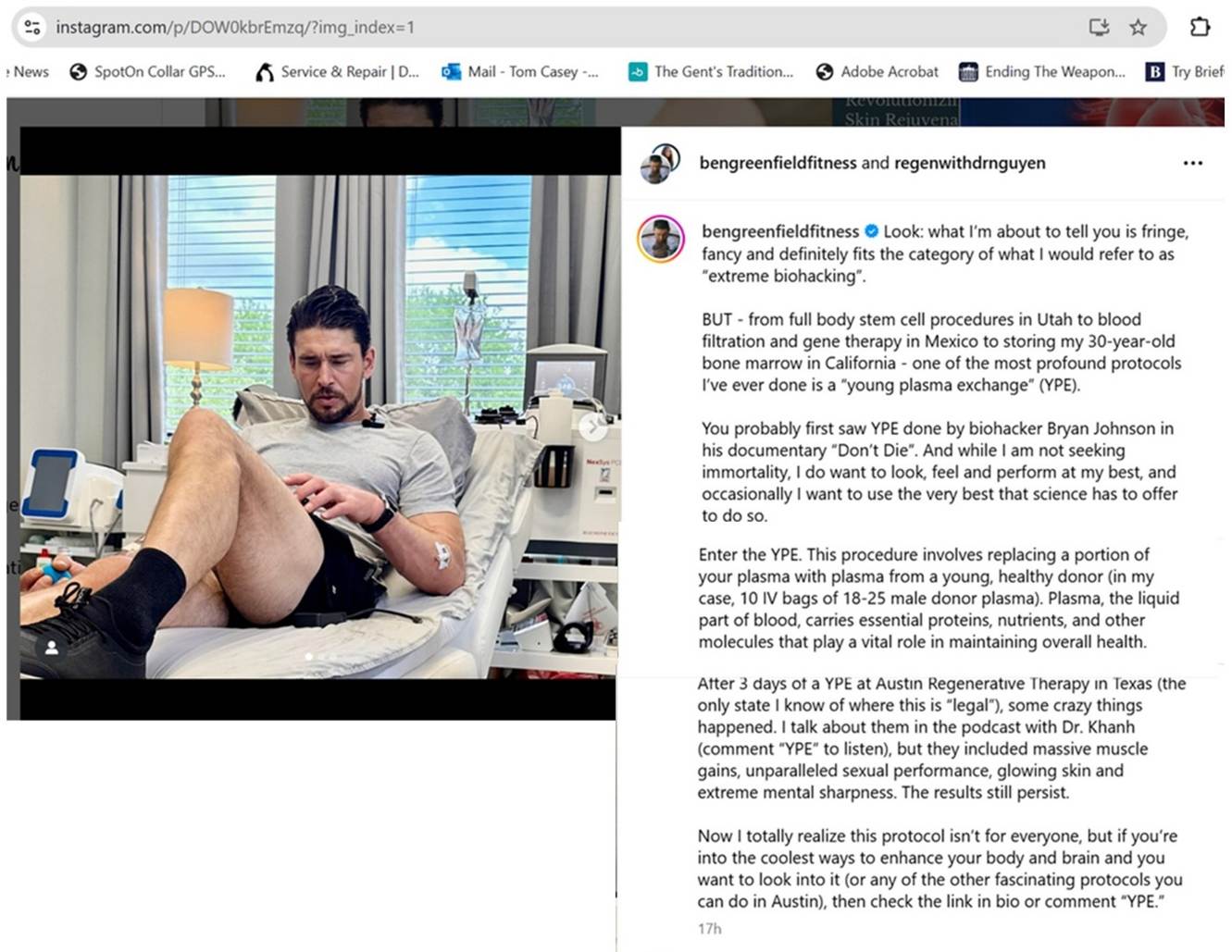

Even though the experiment was in mice, not humans, it kicked off a US West Coast craze for “young blood”. One tech billionaire — the longevity evangelist Bryan Johnston — tried out transfusions of plasma, the liquid component of blood that carries blood cells, from his teenage son.

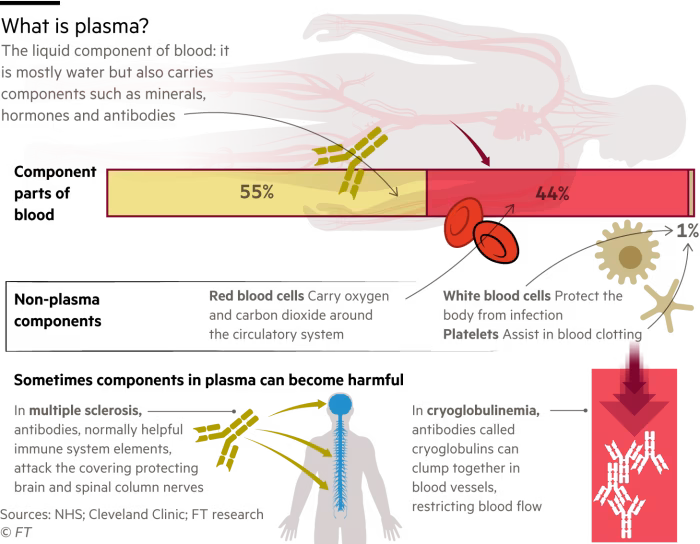

Jörg Schüttrumpf, chief scientific innovation officer of Grifols, said that because plasma was like the “internet of the organs”, carrying substances such as proteins, antibodies and hormones, studying it can be very helpful to gain a wider understanding of the body. “It plays a tremendous role in disease, development, ageing and all kinds of biological processes,” he said.

Wyss-Coray said the “biggest frustration” had been trying to identify the key components in blood that helped or harmed neurological function. There was now an acceptance, he added, that there were myriad factors. “It’s really almost like a cocktail that has these beneficial effects,” he said. “So an ideal drug would mimic both: neutralising some of the most prominent negative factors and then supplying you with the younger factors.”

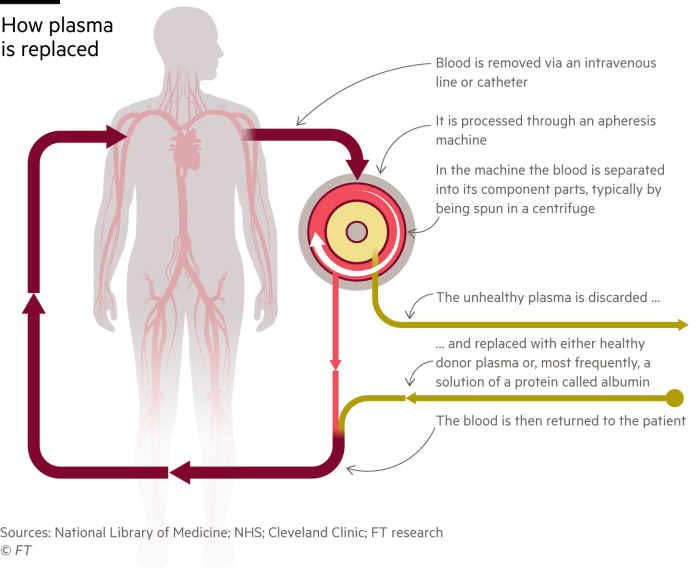

While Grifols invests in the long-term work of finding drug candidates, it is also running a pilot in Barcelona for treating Alzheimer’s disease with therapeutic plasma exchange: an hour-long process where a machine removes 2.5 litres of a patient’s plasma and replaces it with a solution containing the protein albumin.

Schüttrumpf said small studies had shown the treatment was as effective as current Alzheimer’s drugs, but without the risk of common side effects of swelling and small bleeds in the brain. Because the procedure is already used to treat other conditions, it does not need the same level of regulatory approval as a new drug. Grifols said that doctors can use it according to the recommendations of medical societies.

The company is also working with the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research to try to understand what triggers Parkinson’s disease. With a database that stretches back 15 years, Grifols can examine blood from before a person started to develop it. There are an average of 20,000 proteins in a sample that could lead to answers.

Wyss-Coray thinks that while early efforts to use therapeutic plasma exchange to slow ageing was “without any scientific basis”, this is changing. “Now I think there’s enough scientific evidence that . . . as a physician, if you do this, you don’t even have to feel bad.”

Read the full story: The quest to make young blood into a drug (FT)

This is the first part of a five-part FT series examining the business and science of longevity

Part one: Inside the billion-dollar quest to live forever

Part two: Start-up takes aim at ageing with drug to block cell death

Part three: The quest to make young blood into a drug

Part four: The supplement that promises youth but awaits full proof

Part five: US “wellness” industry scents opportunity to go mainstream