Balancing Nutrition and Inflammation: The Role of a Healthy Diet in NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

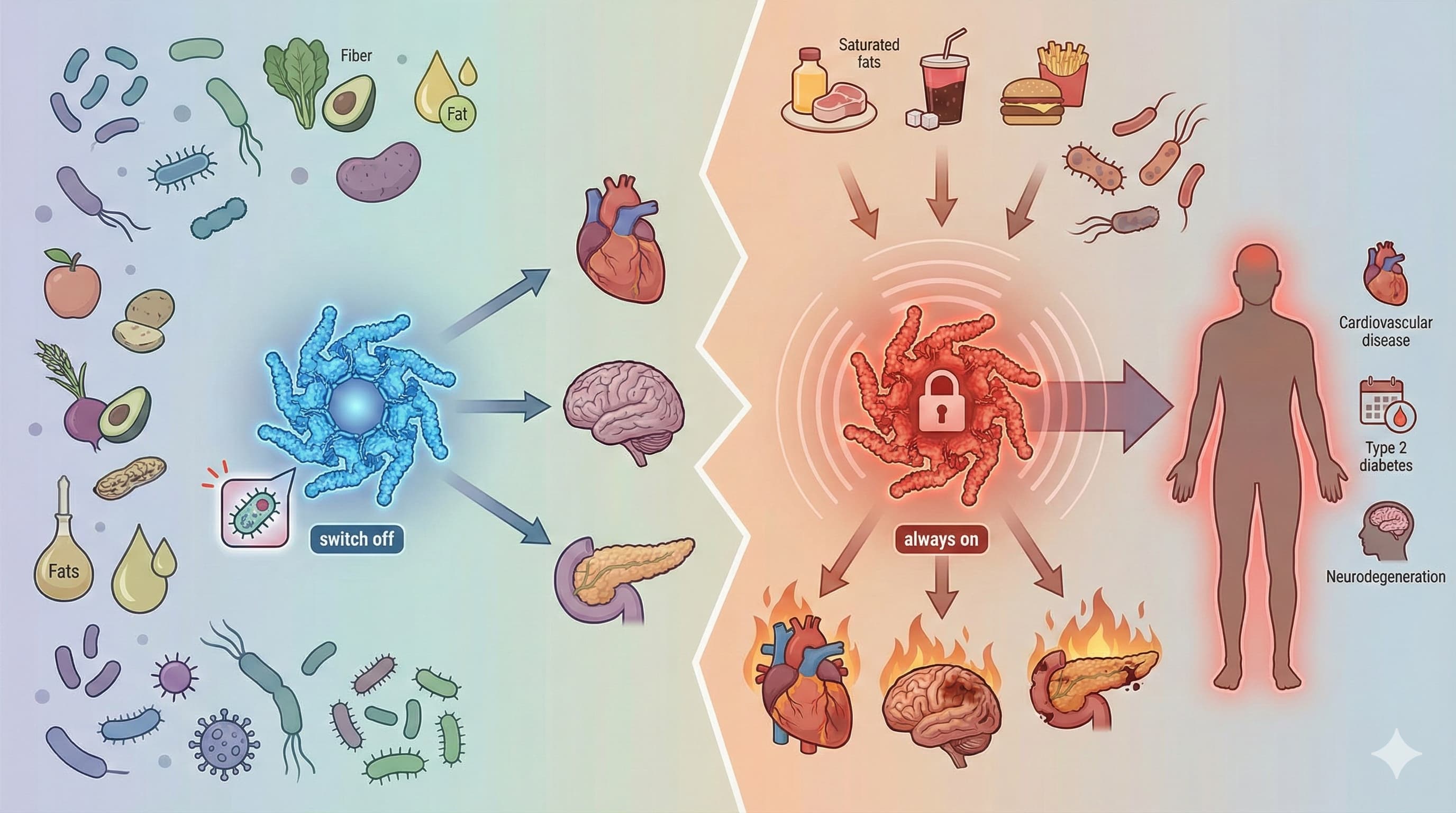

A new review from the Amsterdam UMC in The Netherlands, published in Immuno, frames the NLRP3 inflammasome not merely as an immune sensor, but as the central metabolic “pilot light” of chronic inflammation and aging. While the inflammasome is critical for defense against pathogens, this paper argues that modern dietary inputs—specifically the interplay between lipid saturation, sugar metabolism, and gut dysbiosis—keep this switch permanently flipped to “on” in metabolically compromised individuals. This chronic hyperactivation drives the low-grade systemic inflammation (inflammaging) that underpins cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and neurodegeneration.

The core narrative shifts away from viewing foods solely as “calories” or “macros” and reclassifies them as molecular signaling agents that directly modulate mitochondrial integrity and lysosomal stability. The authors synthesize evidence showing that Saturated Fatty Acids (SFAs) like palmitic acid do not just add adipose mass; they physically rigidify cell membranes and disrupt the Na+/K+ pump, causing potassium efflux—a direct trigger for NLRP3 assembly. Conversely, the review highlights a critical nuance often missed in biohacking circles: the context-dependent nature of “healthy” compounds. For instance, Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) like butyrate are generally anti-inflammatory, but in the presence of existing bowel inflammation, they can paradoxically enhance NLRP3 activation.

Ultimately, the paper champions the “Food Matrix” concept, suggesting that the reductionist isolation of nutrients (e.g., taking a curcumin supplement vs. eating turmeric in a meal) often fails because it ignores the synergistic signaling required to dampen the inflammasome. For the longevity enthusiast, the takeaway is clear: metabolic health is maintained by keeping the NLRP3 pilot light dim, achieved not just by avoiding sugar, but by rigorously balancing the Omega-6/3 ratio and leveraging specific polyphenols to enforce mitochondrial quality control (mitophagy).

Source:

Related Reading:

1 Like

Follow-on prompt:

What foods in the common USA diet have higher levels of palmitic acid?

Gemini Pro Response:

Palmitic acid (C16:0) is the most common saturated fatty acid in the standard American diet. It is ubiquitous because it is the primary solidifying fat used by the food industry to replace trans fats (partially hydrogenated oils), and it naturally occurs in high concentrations in animal products.

You can categorize foods high in palmitic acid into three main tiers: Industrial Ingredients (highest concentration), Animal Products (high natural occurrence), and Ultra-Processed Foods (hidden sources).

1. The “Big Three” Primary Sources

These are the ingredients that add the most palmitic acid to the American diet.

-

Palm Oil: Roughly 44% palmitic acid by weight. It is the single most concentrated source and is used in thousands of shelf-stable products.

-

Meat Fats (Beef Tallow & Lard): Palmitic acid makes up about 25–30% of the fat profile in beef, pork, and other red meats.

-

Dairy Fat (Butter & Cream): Palmitic acid constitutes roughly 25–30% of the fatty acids in milk fat.

2. High-Level Common Foods (Specific Examples)

Based on nutritional data, these common items contain significant amounts of palmitic acid per serving:

Dairy & Cheese

Full-fat dairy is a major contributor.

-

Hard Cheeses: Parmesan, Cheddar, Provolone, and Swiss.

-

Soft Dairy: Butter (one of the purest animal sources), heavy cream, and full-fat ice cream.

-

Pizza Cheese: The processed mozzarella used on commercial pizzas is a potent delivery vehicle for palmitic acid due to the volume consumed.

Red Meat & Processed Meats

The fattier the cut, the higher the palmitic acid load.

-

Processed Meats: Salami, pepperoni, sausage, and bacon.

-

High-Fat Cuts: Ribeye steaks, 80/20 ground beef, and pork belly.

-

Poultry Skin: While chicken fat is higher in unsaturated fats than beef, the skin still contains significant palmitic acid (approx. 20–22% of the fat profile).

Baked Goods & Sweets (The “Hidden” Sources)

These items often rely on palm oil or palm kernel oil for texture and shelf stability.

-

Commercial Baked Goods: Pie crusts (frozen or store-bought), donuts, cookies, and biscuits often list “Palm Oil” as the second or third ingredient.

-

Frosting & Icings: Canned frostings are almost entirely sugar and palm oil.

-

Chocolate Compounds: Candy bars, especially those with “chocolatey coatings” rather than pure cocoa butter, often use palm oil fractions.

-

Hazelnut Spreads: Popular brands (like Nutella) are primarily sugar and palm oil.

3. “Healthy” Fats with Palmitic Acid

Even foods considered healthy sources of fat contain palmitic acid, though in lower ratios compared to the sources above.

-

Cocoa Butter: High in stearic acid, but also contains ~25% palmitic acid. Dark chocolate is a source.

-

Olive Oil: Contains roughly 8–20% palmitic acid (mostly unsaturated fats, but the saturated portion is largely palmitic).

-

Avocado Oil: roughly 10–20% palmitic acid.

Summary Table: Palmitic Acid Content in Fats

| Fat Source |

Approx. % Palmitic Acid |

Primary Dietary Vehicle |

| Palm Oil |

~44% |

Processed foods, baked goods, snacks |

| Butter |

~29% |

Baking, spreads, sauces |

| Beef Tallow |

~26% |

Burgers, steaks, deep frying (sometimes) |

| Lard (Pork Fat) |

~24% |

Pastries, sausages, bacon |

| Chicken Fat |

~22% |

Poultry skin, fried chicken |

| Olive Oil |

~13% |

Dressings, cooking oil |

Why is it so common now?

In the 2010s, when the FDA moved to ban trans fats, the food industry needed a replacement fat that remained solid at room temperature (to keep cookies from melting and give crackers a “snap”). Palm oil—rich in palmitic acid—was the cheapest and most functional natural alternative, leading to a massive surge in its presence in the US food supply.