This is an interesting area:

Researchers have identified a new form of dementia that is often mistaken for Alzheimers but is less severe and doesn’t have the signature amyloid protein. Called LATE, for Limbic-predominant age-related encephalopathy, it affects about a third of people over 85. A mild condition on its own, when combined with Alzheimers it ravages the brain.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/28/health/late-dementia-alzheimers.html

@adssx , you’ve probably already looked at this, but it seems like this might have potential in Parkinson’s also…

The Effect of Exogenous Ketone Bodies on Cognition in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease and in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Open access Paper:

The owner of KetoneAid had me excited about this a couple of years ago. Their KE4 product is a great source of exogenous ketones. Their “Hard Ketones” can be a beer substitute (doesn’t taste that great though).

He has lots of reports of individuals with dementia symptoms who reportedly had marked improvement with this product.

As with many other things I’ve tried utilizing, my patient population didn’t seem to have any response to this treatment - however, I was utilizing it on individuals with a vague sense of mental sharpness decline, often in the setting of having an ApoE4 and being older.

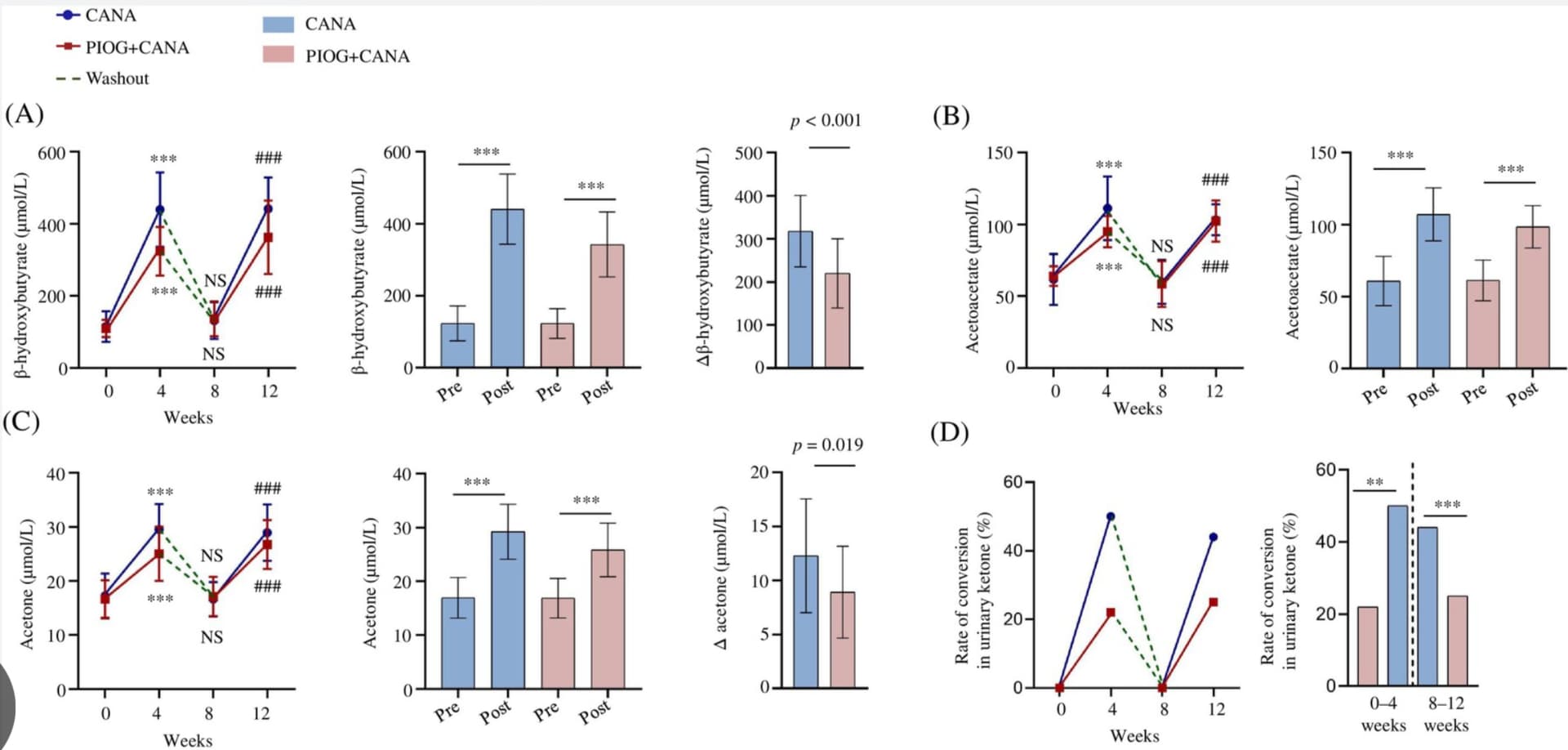

Yes ketone drinks look interesting. There’s an ongoing trial in PD in the UK. I wonder if SGLT2i could achieve the same result as they shift the brain metabolism towards ketone use: Empagliflozin Induced Ketosis, Upregulated IGF-1/Insulin Receptors and the Canonical Insulin Signaling Pathway in Neurons, and Decreased the Excitatory Neurotransmitter Glutamate in the Brain of Non-Diabetics 2022

Effects of Ketone Bodies on Brain Metabolism and Function in Neurodegenerative Diseases

CAUTION: Chinese paper.

Pioglitazone reduces serum ketone bodies in sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor-treated non-obese type 2 diabetes: A single-centre, randomized, crossover trial

From New Scientist:

Your brain undergoes four dramatic periods of change from age 0 to 90

Our brain wiring seems to undergo four major turning points at ages 9, 32, 66 and 83, which could influence our capacity to learn and our risk of certain

The brain has distinct regions that exchange information via white matter tracts – wiry structures made of spindly projections, called axons, that project from neurons, or brain cells. These connections influence our cognition, such as our memory. But it was unknown whether major shifts in this wiring occur throughout life. “No one has combined multiple metrics together to characterise phases of brain wiring,” says Alexa Mousley at the University of Cambridge.

To fill this knowledge gap, Mousley and her colleagues analysed MRI brain scans from around 3800 people in the UK and US, who were mostly white, and ranged in age from newborns to 90. These scans were previously taken as part of various brain imaging projects, most of which excluded people with neurodegenerative or mental health conditions.

The researchers found that among people who reach 90, the brain’s wiring has generally undergone five main phases, separated by four key turning points.

In the first phase, which occurs between birth and 9 years old, white matter tracts between brain regions seem to become longer, or more convoluted, making them less efficient. “It takes longer for information to pass between regions,” says Mousley.

This could be because our brain is packed with lots of connections as infants, but as we grow and experience things, the ones we don’t use are gradually pruned away. The brain seems to prioritise making a broad range of connections that are useful for things like learning to play the piano, at the cost of them being less efficient, says Mousley.

But during the second phase, between 9 and 32 years old, this pattern seems to flip, which is potentially driven by the onset of puberty and its hormonal changes influencing brain development, says Mousley. “Suddenly, the brain is increasing the efficiency of the connections – they become shorter, so information gets from one place to another more quickly.” This may support the development of skills like planning and decision-making, and improvements in cognitive performance, such as working memory, says Mousley.

Read full story: Your brain undergoes four dramatic periods of change from age 0 to 90

Open access paper:

Topological turning points across the human lifespan

Liraglutide might have succeeded where semaglutide failed?

Liraglutide in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a phase 2b clinical trial 2025

Liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist and antidiabetic drug, has shown neuroprotective effects in animal models. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of liraglutide in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease syndrome. ‘Evaluating liraglutide in Alzheimer’s disease’ (ELAD) is a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 204 participants with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease syndrome with no diabetes. Participants received daily injections of liraglutide or placebo for 52 weeks. They underwent fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and detailed neuropsychometric evaluations. The primary outcome was a change in cerebral glucose metabolic rate. Secondary outcomes were safety and tolerability and cognitive changes. The primary outcome showed no significant differences in cerebral glucose metabolism (difference = −0.17; 95% confidence interval: −0.39 to 0.06; P = 0.14) between the two groups. The secondary outcome—score on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Executive domain (ADAS-Exec)—performed better in liraglutide-treated patients compared to placebo (0.15; 95% confidence interval: 0.03−0.28; unadjusted P = 0.01). No significant differences were observed in Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL) (−0.58; 95% confidence interval: −3.13 to 1.97; unadjusted P = 0.65) or Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SoB) (−0.06; 95% confidence interval: −0.57 to 0.44; unadjusted P = 0.81) scores. Liraglutide was generally safe and well tolerated in non-diabetic patients with Alzheimer’s disease. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01843075.

Liraglutide crosses the BBB better than semaglutide.

Not sure if discussed already, if not might be worth a discussion

Looks promising?

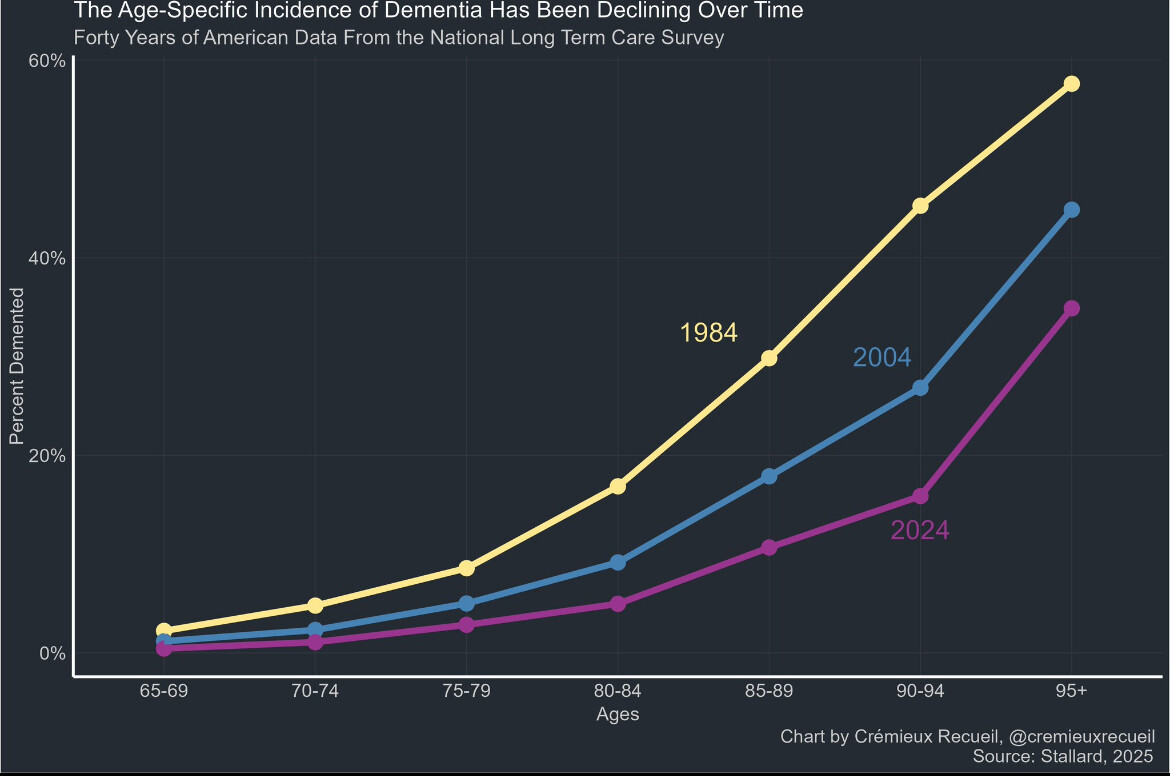

The age-specific incidence of dementia has dropped sizably over the last few decades:

Today’s 90-year-olds have less than half the risk of dementia that ones in 1980s did!

I think it’s the same reason why people are not dying from CVD in their 50’s anymore (see CVD mortality graph over the past 100 yrs), better fat consumption of more unsaturated fats compared to saturated, even if it’s from processed food, better and more treatment, awareness of risk factors for CVD.

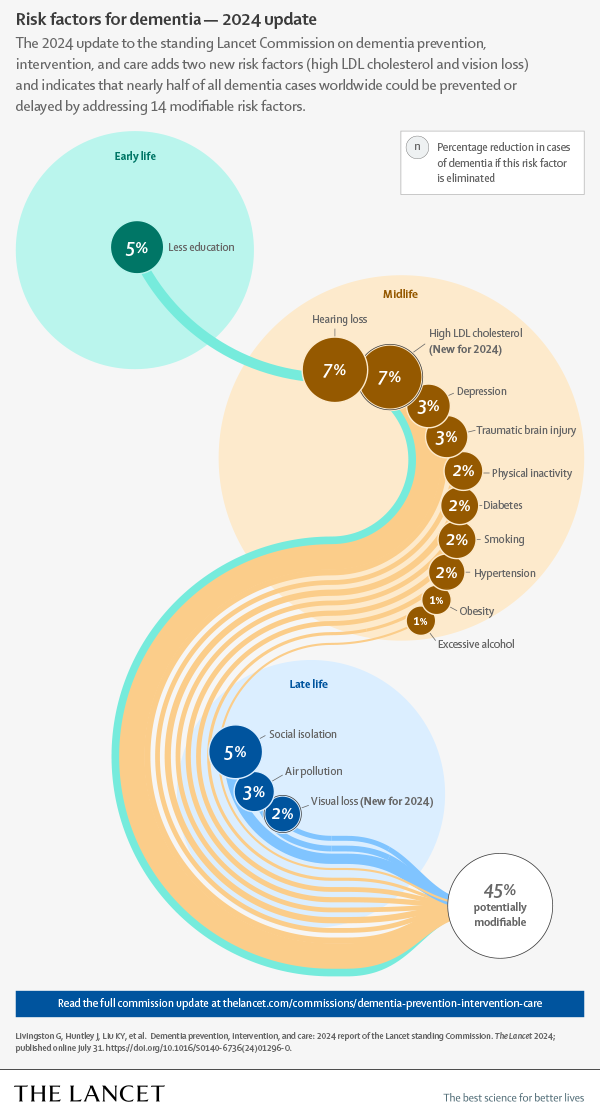

We know about half of the risk factors for dementia:

Most have improved over time (better education, earlier and better treatments for hearing loss, cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity), people drink and smoke less and air pollution has improved. So the lower incidence is expected. But how low can it go with those preventive measures only?

More playing video games associated with slower brain aging.

The brains of experienced gamers looked an estimated four years younger

On gaming and brain health:

Gaming expertise induces meso‑scale brain plasticity and efficiency mechanisms:

https://www.sciencedirect.com:5037/science/article/pii/S1053811924001289

Gaming and broader of creative activities:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-64173-9

@DrFraser @adssx @AlexKChen and others - any aspects of this part of your protocols?

Play novel games, play ones that are RTS, play ones that are mildly uncomfortable, play 1v1’s multiplayer so you can’t count on allies, play games that are shorter rather than longer, and play from a variety of input modalities you havent hard-learned

play games with adaptive rulesets!!

play games that older people don’t prefer playing (don’t just do city-builders or total war). play games that force you to be mindful rather than rote-based

most of all, play games that get you in touch with younger generations (b/c being robust friends with younger generations really is the best bulwark against cognitive aging). But make sure these communities last [the era of online forums was so much better, now discord/reddit/steam communities don’t last as long]. Don’t use gaming as a substitute for social interaction. Don’t play WoW more than a few hours.

play games where you can measure changes in plasticity/probabilistic response over time

Idk if the effects really last (if you only play occasionally, natural aging will wash out any benefits)

But yea, go do HOMEWORLD, XCOM2 [go 1v1 Ramses Alcaide if you can], or Sins of a Solar Empire II, supreme commander, or Ashes of the Singularity 2 once in a while. Get gaming buddies. Starcraft works too but there are so many new games with learning curves. and try a flight-combat game

as petard_rusher once said, “I own at all RTS” [we all played SWGB demo the first time it came out]

and hell, vibe-code an advanced keystrokes=>entropy/complexity analysis visualizer

Try AOE3 [cuz it’s free]

there was a spanish study on how expert gamers had slower-aging brains (selection-effect-maybe)

and track how well TheViper and DauT and TaToH are doing over time [they don’t have great diets]…

and maybe try microdosing psilocybin while you’re at it

if the first 13 minutes weren’t always the same, AOE2 could be ideal, but the first 13 minutes is so repetitive and no one wants to play empire wars/deathmatch, but if you want that game and have any value for time, go for DM]. AI will soon get as better as human players do.

if ur going to do AOE2 DM, don’t do it post-imperial age (tho even post-imperial age is better than RM). at least watch some T90Official regicide rumble games [regicide is way better than RM b/c the start is faster so the first 10 minutes isn’t always the same]. NONSTANDARD SETTINGS [even RM high resources] is way better

I remember when my smart friend [david feldman] used to play Sins of a Solar Empire LAN parties, and even played AI wars [a lot of novel games]. Another friend from UW EEP liked Ark: Combat Evolved…

and go try new kinect or body-aware games. VR/AR games still suck but this will change.

even some UW pathology profs like gaming…

[also try to make the screen flicker subtly at 40hz if u can]

[and don’t spend your youth playing so many games that you don’t adapt to other environments]. for older people who aren’t prone to gaming addiction or escapism, the downside risk is very low

as one ages, it’s way easier to give up on “high-competence” rather than “adaptive competence” fields, so some games can be more robust for this effect

According to Ray Perez, a program officer in the ONR’s warfighter performance department who discussed the findings in the Pentagon Web Radio Webcast, gamers perform “10 [percent] to 20 percent higher, in terms of perceptual and cognitive ability, than normal people that are non-game players.”

2010

I’m playing off and on a game called The Witness right now, it’s a puzzle game with some spiritual elements and unique game engine mechanics involving the player’s viewport. Looking forward to the designer’s new game Order of the Sinking Star, he also created a new programming language with it.

I played way too much FPS games as a kid – I think that made me permanently good at them

Different games for different types cognitive skills. It uses up a lot of time though. VR games might be good for movement and Quest 3 is really good.

Higher SHBG levels in women probably reduce lifelong LBD, stroke risk, and increase lifespan:

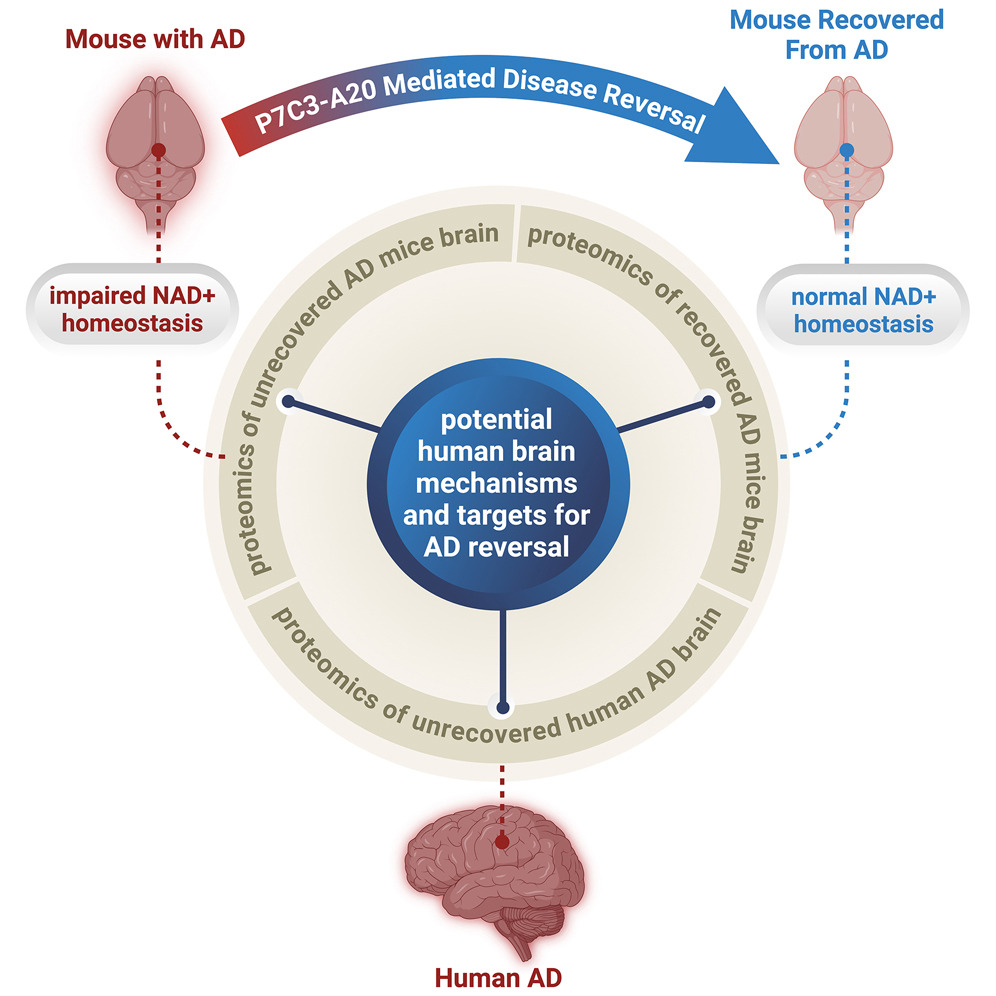

Some good news, but most Alzheimer mouse models have been really useless and don’t transfer to humans well… so we’ll see where this goes:

New Study Shows Alzheimer’s Disease Can Be Reversed in Animal Models to Achieve Full Neurological Recovery, Not Just Prevented or Slowed

Graphical abstract:

They used P7C3-A20: “a neuroprotective compound that restores NAD+ homeostasis without producing supraphysiologic NAD+ levels”. They got it from “Andrew A. Pieper”.

Where can one source that compound @Steve_Combi?

I will check on that.

In the mean time check this out. There may be a better SMC in the same P7C3- family. P7C3-S243

Also one would want to understand,

Human studies - none

LD50 - none established - well tolerated at high doses in mouse studies

Half-life - none established in humans

Dosing per use - none established for humans

Method of dosing - IP, subQ and oral - in vivo

Dosing schedule - 1 week to 38 weeks

HED - For a 70‑kg human, that is ~225 mg/day , often rounded to ~200–250 mg/day as a theoretical equivalent to the primate neurogenesis study.

This would get quite expensive from most research chemical suppliers, due to the dose size.

Major research suppliers

- Focus Biomolecules: Markets P7C3-A20 as a NAMPT activator/proneurogenic agent (5–25 mg sizes), explicitly labeled “for laboratory research use only; not for human or veterinary applications.”

- Aobious: Offers high‑purity (≈98%) P7C3-A20 under CAS 1235481‑90‑9 in multiple mg quantities with typical storage at 0 to −20 °C and DMSO solubility.

- Other catalog vendors: MedChemExpress, Selleck, MedKoo, LKT Labs, Abbexa, TargetMol, and similar companies list P7C3-A20 as a neuroprotective NAMPT activator for in vitro/in vivo research, again strictly labeled research‑only and not for diagnostic or therapeutic use.

mechanistic comparison vs. other NAD boosters (2).pdf (1.1 MB)