Mechanistic Deep Dive

-

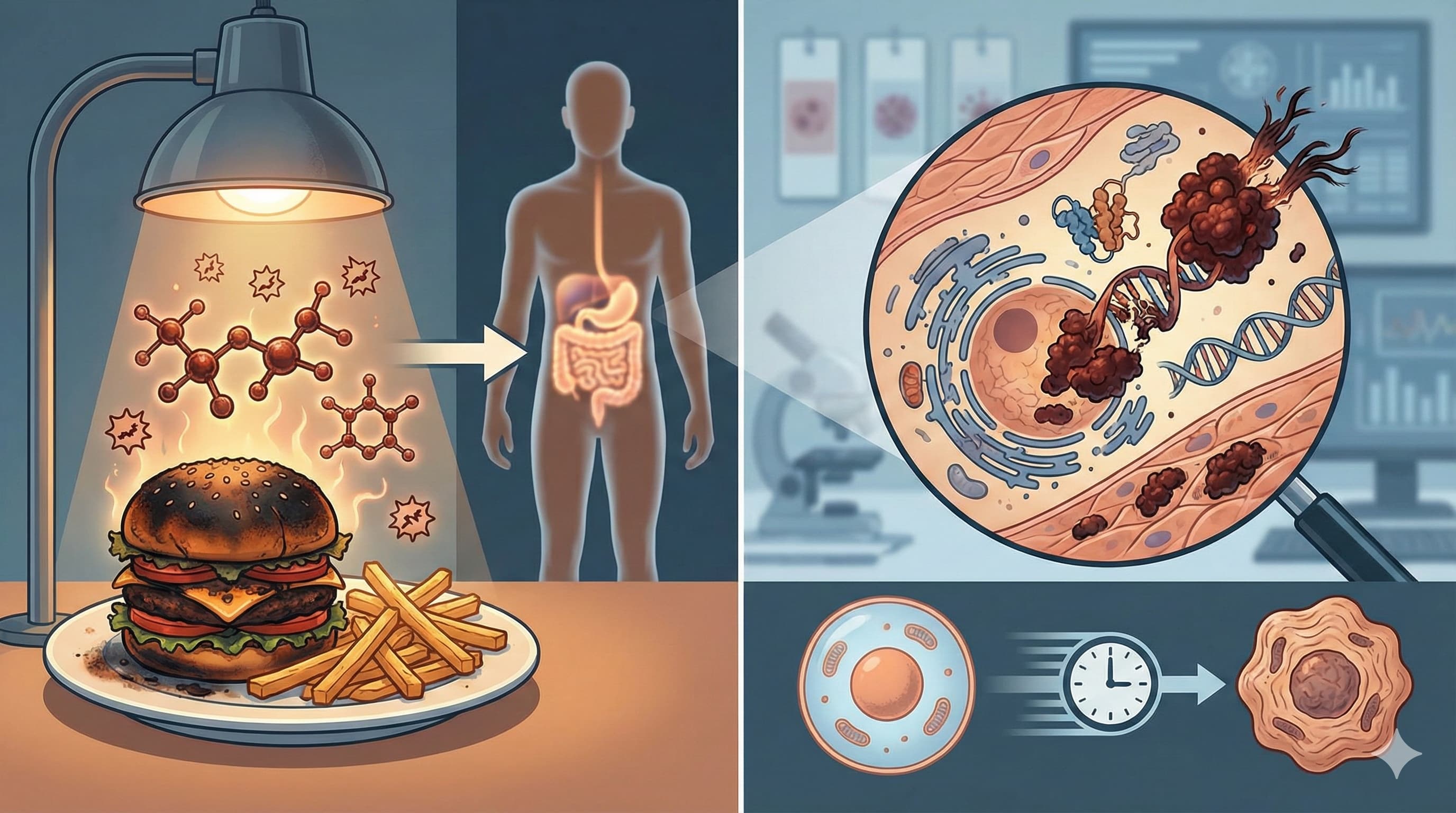

The AGE-RAGE-ROS Axis: RAGE is a multi-ligand receptor that, upon activation by AGEs, stimulates intracellular pathways including MAPKs, Erk 1/2, PI3K/JNK, and the Janus kinase. The convergence of these pathways results in NFkB activation, which promotes the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes and upregulates RAGE expression itself. [Confidence: High]

-

Vicious Cycle of Oxidative Stress: The AGE-RAGE interaction directly generates ROS via the activation of NADPH oxidase. This ROS accelerates the biochemical generation of new AGEs (glycoxidation), which then bind to RAGE, ensuring the sustained propagation of glycation and systemic “inflammaging”. [Confidence: High]

-

Neurodegenerative Protein Aggregation: In Alzheimer’s disease pathology, AGE modification triggers protein misfolding, enhancing the neurotoxicity and propensity of Amyloid-Beta and Tau to form pathological, protease-resistant inclusions. [Confidence: Medium]

-

Vascular Stiffening: AGE accumulation alters the content and arrangement of collagen and elastin in the extracellular matrix, directly contributing to arterial stiffness and Endothelial Dysfunction (EDD). [Confidence: High]

Novelty

-

The Protein Paradox: The paper highlights a critical clinical dilemma for older populations: seniors require high protein intake to prevent sarcopenia, yet animal proteins cooked via dry heat introduce massive dAGE loads. The proposed solution innovates by advising a shift in culinary techniques (e.g., substituting grilling with poaching) rather than dangerous macronutrient restriction.

-

Early Life Biomarkers: The authors introduce the novel utility of measuring fluorescent urinary AGEs as a rapid screening technique to identify subclinical inflammation in otherwise healthy children and adolescents, pushing AGE pathology surveillance earlier in the lifespan. [Confidence: Medium]

Critical Limitations

-

Lack of Definitive Human Trials: While short-term mechanistic data is compelling, the field completely lacks definitive, long-term human intervention trials rigorously quantifying the independent contribution of dAGE restriction to healthspan and lifespan. [Confidence: High]

-

Bioavailability and Fate Unknowns: The precise systemic bioavailability—the fraction of the ingested dose that reaches circulation—of protein-bound dAGEs remains a subject of intense scientific debate. Current evidence regarding their metabolic fate is insufficient, with recent data showing no significant association between dietary intake and urinary fluorescent AGE levels in a youth cohort. [Confidence: Medium]

The Strategic FAQ

1. Are dAGEs actually absorbed into systemic circulation, or do they just pass harmlessly through the gut? The precise bioavailability of protein-bound dAGEs is fiercely debated due to conflicting urinary excretion data. However, even unabsorbed dAGEs interact directly with the intestinal epithelium, actively altering gut barrier function and triggering localized chronic inflammation before excretion.

2. Does acidic marination break down the existing AGEs in animal protein? No. Acidic agents like lemon juice or vinegar inhibit the initial Schiff base formation (the very first step of the Maillard cascade), effectively preventing newdAGEs from forming during thermal processing. They do not possess the chemical capacity to cleave established crosslinks.

3. If I cook meat in a slow cooker (moist heat) for 8 hours, does the long duration negate the low-temperature benefit? Time is a factor, but moisture and temperature are the dominant rate-limiters. Prolonged moist, low-heat methods (like slow cooking or stewing) consistently generate substantially fewer dAGEs than short, high-heat, dry methods like broiling or frying.

4. Is there clinical utility in upregulating Fructosamine-3-Kinase (FN3K) to reverse glycation? While conceptually promising for anti-aging, clinical translation is moving in the exact opposite direction. Elevated FN3K protects cancer cells from oxidative stress by deglycating Nrf2; consequently, biotech pipelines are actively developing FN3K inhibitorsfor targeted oncology FN3K Mechanism (2025). Upregulation is currently too risky for human longevity protocols.

5. How does the “protein paradox” alter sarcopenia protocols for the elderly? High protein intake is strictly required to prevent sarcopenia, but animal proteins cooked at high heat deliver massive, pathogenic dAGE loads. The clinical solution is absolutely not macronutrient restriction, which would induce frailty; the solution is strictly mandating preparation modifications like poaching or steaming.

6. Do endogenous AGEs dwarf the dietary contribution anyway, making cooking methods irrelevant? Endogenous formation is the primary driver in metabolically compromised individuals facing chronic hyperglycemia. However, in metabolically healthy individuals, the modern Western diet provides a massive exogenous pool that acts as an independent, active etiological factor for systemic inflammation, making culinary mitigation highly relevant.

7. Can I rely on standard HbA1c blood tests to measure my total AGE load? No. HbA1c measures an early-stage, reversible Amadori product (fructosamine). It does not quantify irreversible, late-stage tissue cross-linking products like CML, CEL, or pentosidine, which require specialized LC-MS/MS assays or skin autofluorescence Glycation Biomarkers (2021).

8. Does endurance exercise clear existing AGE crosslinks from tissue? Exercise does not directly cleave established structural AGE crosslinks. It acts upstream by upregulating skeletal muscle AMPK and improving systemic insulin sensitivity. This lowers baseline circulating glucose, thereby starving the Maillard cascade of the substrate required for the endogenous formation of new AGEs.

9. Why do high-fat foods have high dAGEs if the Maillard reaction is strictly a sugar-protein reaction? Lipids undergo a parallel cascade to form advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs). Because ALEs are generated under the identical conditions of dry, high heat, and because they bind to and activate the exact same RAGE receptor to induce inflammation, they are analytically and pathologically grouped together with AGEs.