Angiotensin Receptor Blockers Do Not Reduce Risk of Myocardial Infarction, Cardiovascular Death, or Total Mortality: Further Evidence for the ARB-MI Paradox

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/circulationaha.117.026112

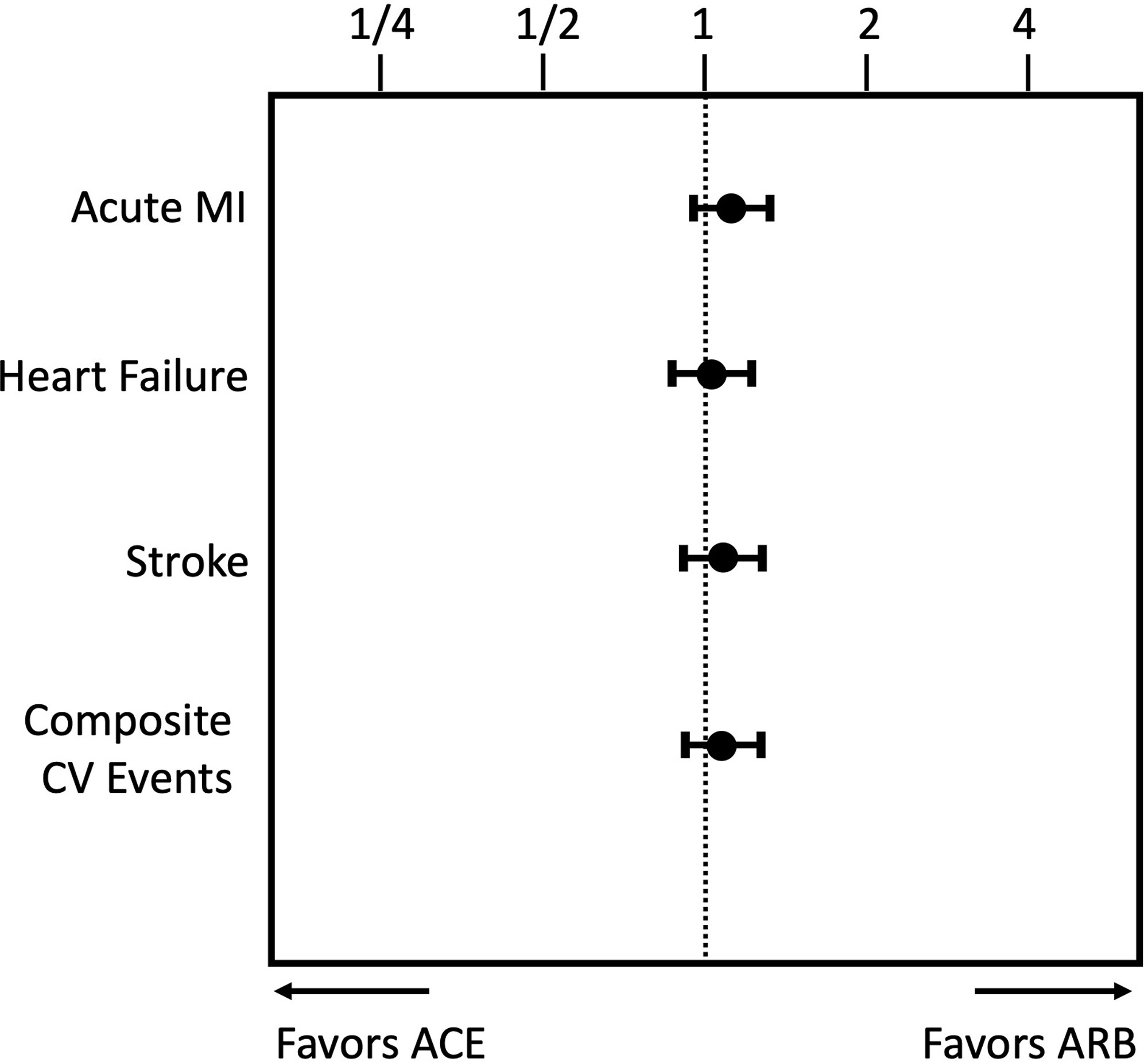

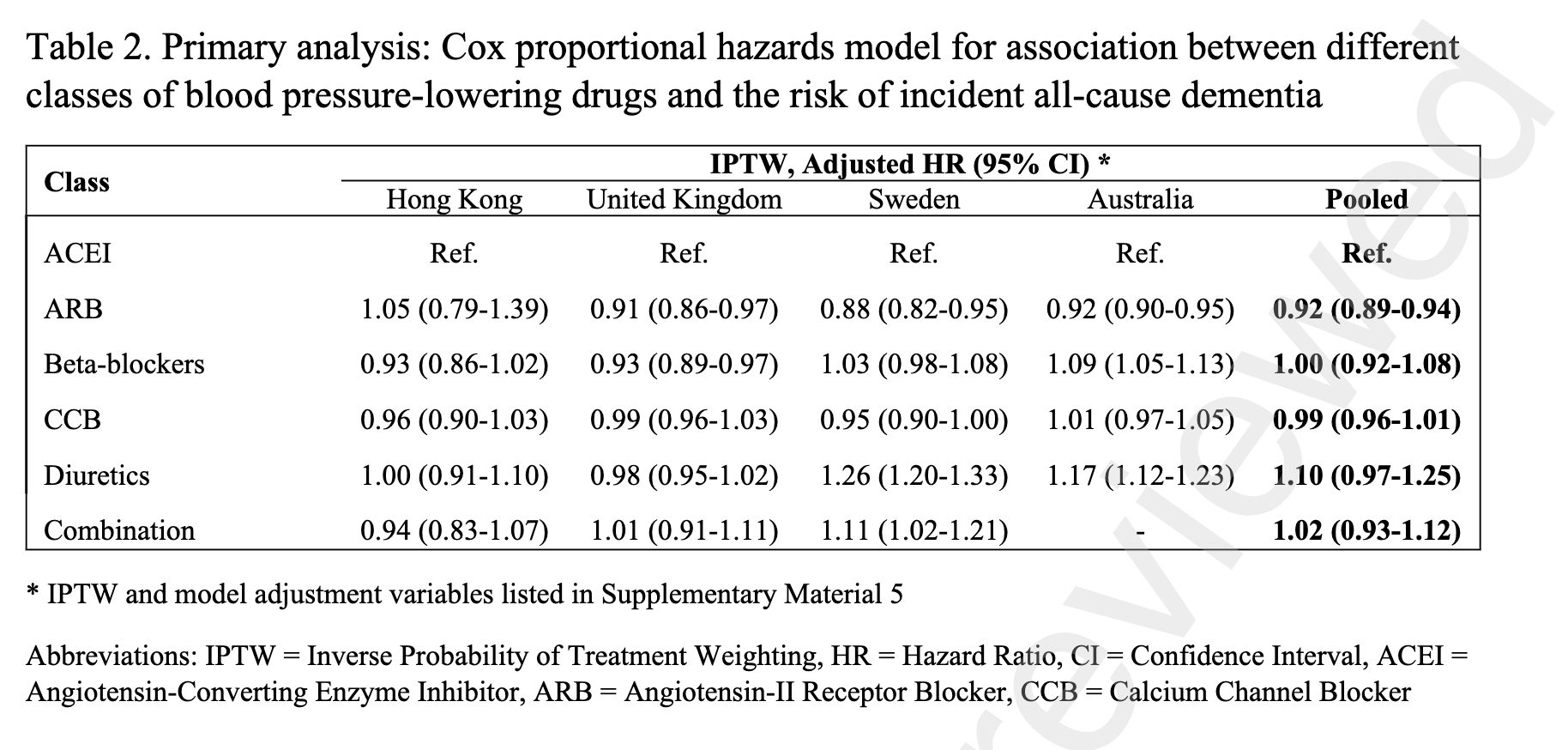

Individual trials of angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and systematic meta-analyses have repeatedly demonstrated the ARB class to significantly reduce systemic blood pressure, stroke, and the subsequent development of heart failure and diabetes mellitus.1 However, no individual trial or meta-analysis has observed an impact of ARB treatment on the incidence of myocardial infarction (MI), cardiovascular mortality, or all-cause mortality (Table). All-cause mortality is the most comprehensive summary indicator of cardiovascular benefit of treatment2 and, consequently, it is surprising that ARBs have no impact given the other clinical benefits we have just acknowledged.

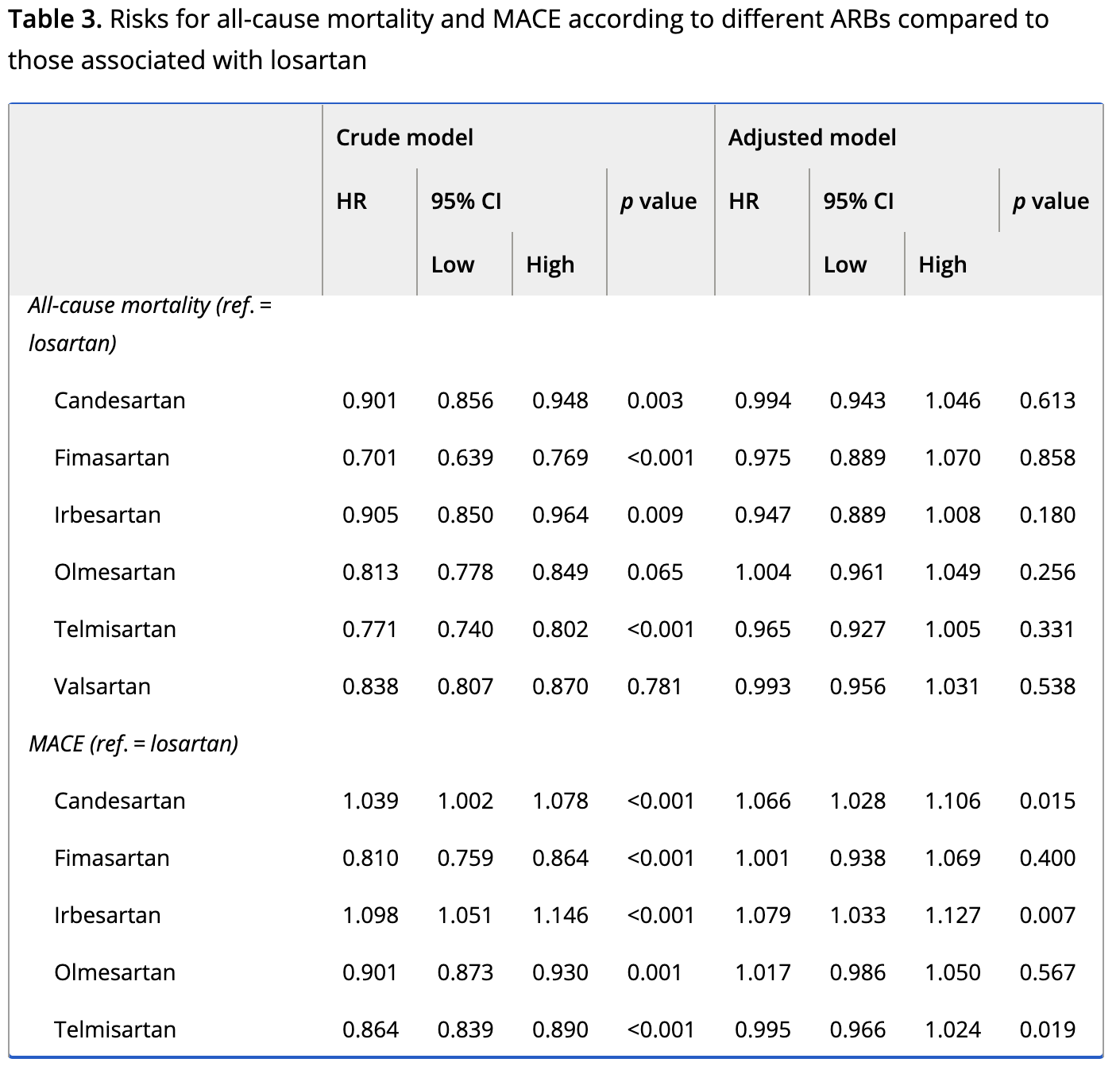

A systematic review/meta-analysis conducted by Bangalore et al3 demonstrated that in 20 trials of ARB versus placebo (n=66 282) and 21 trials of ARB versus active comparator (n=39 738), ARB in no individual trial improved all-cause mortality. Furthermore, when the trials were analyzed in combination, the impact of ARB on mortality was precisely zero compared with placebo (odds ratio, 1.01; 95% confidence limit, 0.96–1.06) and virtually zero compared with an active comparator (odds ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence limit, 0.95–1.03). Placebo-controlled trials are the most rigorous method of assessing treatment efficacy (as well as harm), and, consequently, it is concerning that other meta-analyses of ARBs versus placebo-controlled trials have also reported a lack of mortality reduction in patients with high risk (Savarese),4 those with diabetes mellitus (Cheng),5 and patients with hypertension (Thomopoulos et al),6 as well as no reduction in MI or cardiovascular mortality (Table).

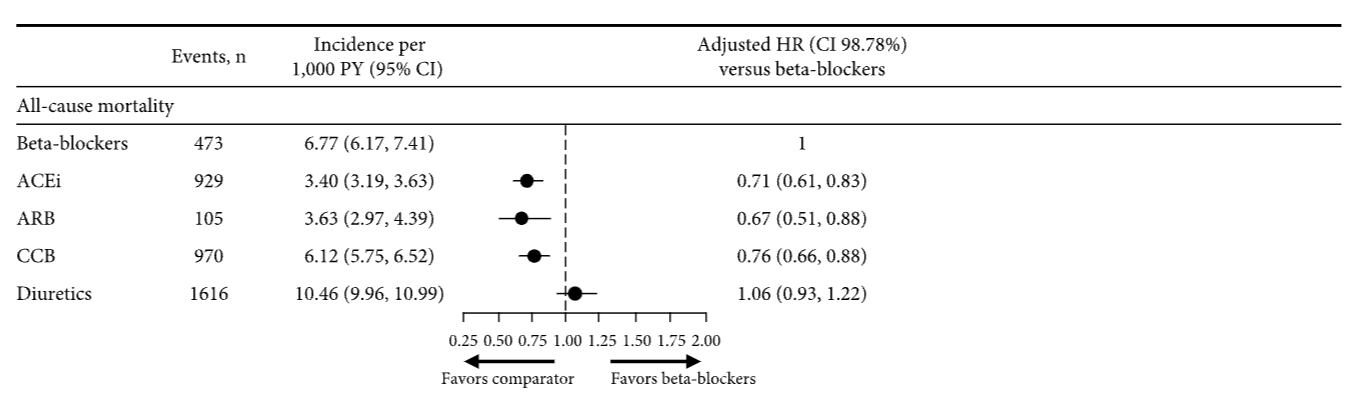

Thomopoulos et al6 also reported the impact of different drug classes compared with placebo in the treatment of systemic hypertension. Indapamide, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) all statistically significantly reduced mortality, whereas 4 other drug classes reduced mortality but not to a degree that was of statistical significance. ARB was the only drug class that failed to reduce death compared with placebo, despite representing the largest group of patients studied (n=65 256) and despite an average blood pressure reduction of 3.7/2.0 mm Hg. Because stroke was reduced by ARBs, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality must have been driven by an excess risk of fatal MI and sudden death. ACEIs but not ARBs reduced coronary heart disease (including nonfatal MI) and cardiovascular death (including fatal MI6), despite both being inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

ACEIs suppress angiotensin II, thereby preventing pathological effects, but they also prevent the breakdown of bradykinin, thereby inducing additional cardioprotective effects. This profile is distinct from the one achieved by use of an ARB that induces selective antagonism of the AT1 angiotensin II receptor, inhibiting a negative feedback loop and consequently increasing angiotensin II levels by 200% to 300%. This may lead to MI as a result of stimulation of the AT2 receptors, which are markedly upregulated and active in atheromatous plaques.1 ACEIs in meta-analyses of placebo-controlled trials conducted in parallel to the ARB meta-analyses discussed above (Thomopoulos et al,6 Savarese,4 Cheng,5 Bangalore et al3) demonstrated a robust 9% to 11% risk reduction in all-cause mortality, 10% to 17% risk reduction in cardiovascular mortality, and 17% to 19% risk reduction in MI (all P<0.05; Table). The divergent effects of ACEI and ARB on both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality are despite their comparator arms having similar risks of both (7.8% versus 9%, 4.7% versus 5.2%, respectively).3

These observations are consistent with an earlier meta-analysis1 that reported that ARBs versus all comparators (11 trials, n=55 050) did not reduce mortality (odds ratio, 1.01; 95% confidence interval, 0.96–1.06, P=0.8) and the risk of MI actually increased 8% (odds ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.01–1.16; P=0.03), with that increase qualitatively apparent in 9 of the trials and statistically significant in 2. This article also included a parallel meta-analysis of ACEI trials. ACEIs versus all comparators (39 trials, n=150 943) reduced the relative risk of total mortality 9% (P<0.0001) and MI by 14% (P<0.0001). The divergent effects in the parallel ACEI and ARB meta-analyses on MI and death were marked, despite their comparator arms having similar cardiovascular risks; rates of global death, MI, and stroke (cerebrovascular accident) were essentially no different (13% versus 14%, 5.8% versus 6.3%, and 4.2% versus 4.4%, respectively). In addition, blood pressure lowering comparable to the risk reduction in stroke, a blood pressure–dependent phenomenon, was also similar.

Divergent cardiovascular effects of ACEIs and ARBs were also confirmed in a meta-regression analysis (n=146 838) by the BPLTTC (Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration), as well as being independent of blood pressure lowering.1 For any given blood pressure reduction, ACEIs also reduce the risk of coronary heart disease by an additional 9% (P=0.002), independently of the effects of blood pressure lowering. In contrast, ARBs had no blood pressure–independent effects on coronary heart disease; rather, there was a small, nonsignificant increase in the risk of harm of 7% (–7%: 95% confidence interval, 7 to –24; P=NS), a phenomenon we have called the ARB MI paradox. Specifically, it is paradoxical that no net benefits are observed with ARBs. Furthermore, and most important, for any given blood pressure reduction, ACEIs reduced the risk of MI and death an additional 15% (P=0.002) above that of an ARB.

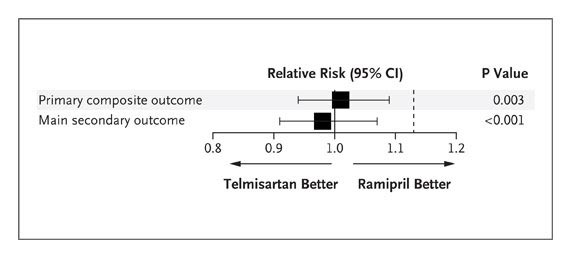

Head-to-head trials of ARB versus ACEI are of interest, but there is a paucity of data. In the ONTARGET trial (Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial),2 the largest ACEI versus ARB controlled trial reported to date (n=17 118), the ARB telmisartan was not statistically equivalent to the ACEI ramipril for a combined cardiovascular end point. The US Food and Drug Administration approved telmisartan as a second-line therapy for those high-risk patients who are ACEI intolerant (New Drug Application 20–850). This decision was influenced by a lack of superiority of telmisartan compared with placebo in the parallel TRANSCEND trial (Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease), consistent also with the HOPE-3 trial (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation-3) conducted in patients at intermediate risk (n=12 705; follow-up, 5.6 years)4 in whom candesartan combined with hydrochlorothiazide failed to reduce a combination of cardiovascular events despite a robust reduction in blood pressure of 6.0/3.0 mm Hg.

Angiotensin Receptor Blockers May Increase Risk of Myocardial Infarction

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594986