New research from York University in Toronto challenges the prevailing view of how our muscles age, identifying a specific “garbage disposal” failure that exercise can reverse. For years, longevity science focused on mitophagy—the tagging of damaged mitochondria for removal—as the primary bottleneck in muscle aging. However, a comprehensive review published in Experimental Physiology by Anastasiya Kuznyetsova and Dr. David A. Hood suggests the problem isn’t identifying the trash, but destroying it.

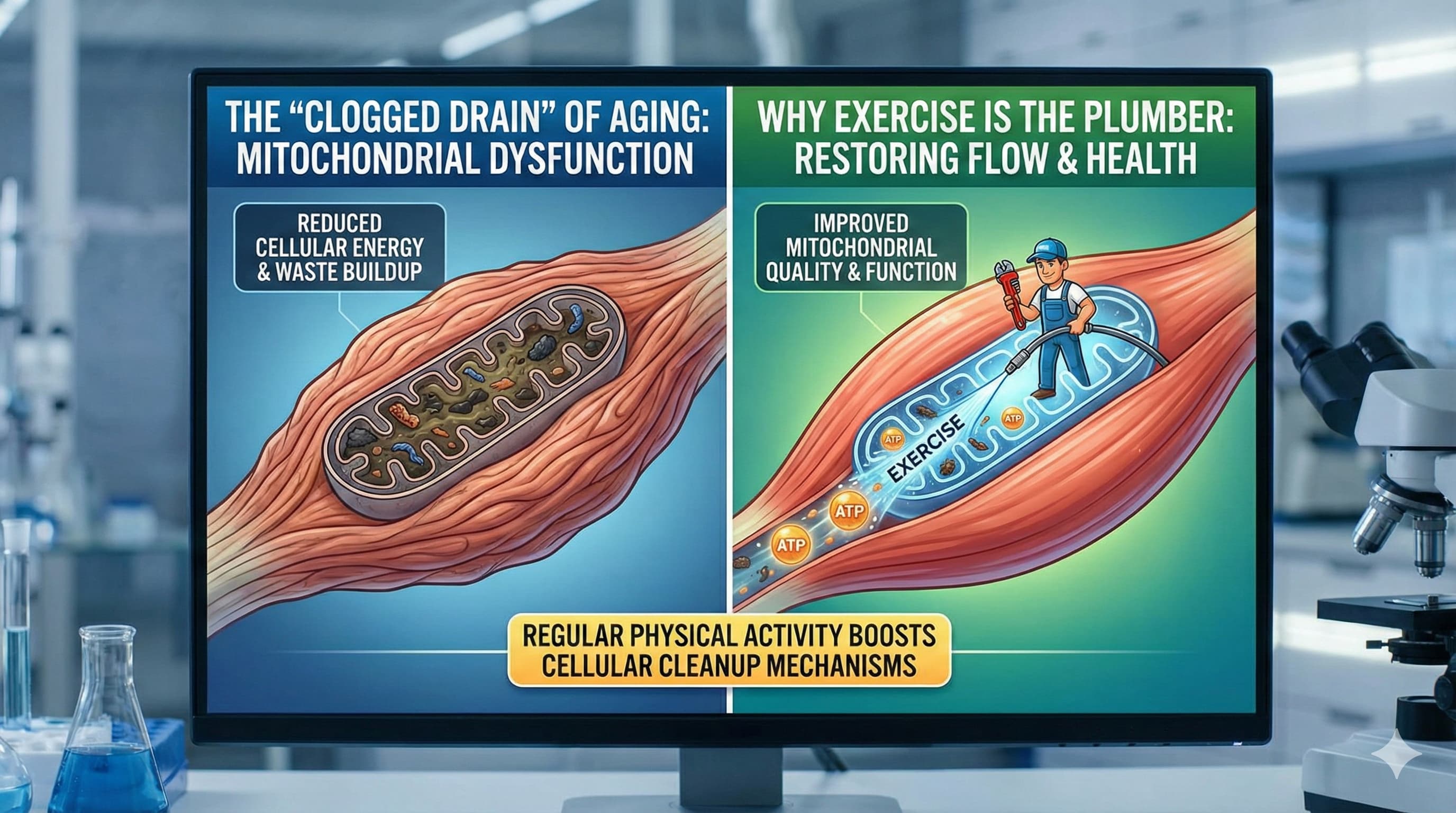

The study highlights that aging skeletal muscle is not starved of mitophagy signals; in fact, it is often overflowing with them. Aged muscle cells show a paradoxical increase in lysosomal proteins (the cellular incinerators) and mitophagy markers. The critical failure occurs at the terminal step: the lysosomes themselves become “clogged” with undigested cellular debris (lipofuscin) and lose their proteolytic (protein-chopping) acidity. This effectively turns the muscle cell into a hoarding situation where marked trash accumulates because the incinerator is broken.

Crucially, the researchers detail how specific forms of exercise—specifically chronic endurance-style contractile activity—act as a lysosomal “reboot.” Exercise doesn’t just stimulate the creation of new mitochondria (biogenesis); it restores the acidity and enzymatic efficiency of lysosomes, allowing them to finally clear the backlog of dysfunctional organelles. This finding shifts the target for longevity interventions from simply “triggering autophagy” to “restoring lysosomal acidity,” offering a more precise roadmap for preventing sarcopenia and maintaining metabolic flexibility into late life.

Mechanistic Interpretation

- The Bottleneck is Downstream: The paper argues that upstream signaling (AMPK activating ULK1, or PINK1/Parkin tagging mitochondria) often remains intact or even hyperactive in aging as a compensatory mechanism.

- Lysosomal dysfunction: The core pathology is a loss of lysosomal proteolytic capacity (likely due to rising pH or enzyme deactivation) and the accumulation of lipofuscin (indigestible protein aggregates), which physically blocks further degradation.

- TFEB Regulation: Exercise activates Transcription Factor EB (TFEB), the master driver of lysosome biogenesis, which not only builds more lysosomes but “refreshes” the enzymatic pool, restoring the ability to degrade cargo.

Novelty

- Paradigm Shift: Contradicts the idea that aging is purely a “deficiency” of autophagy signals. Instead, it frames aging as a “traffic jam” or “indigestion” where the cell tags waste faster than it can degrade it.

- Hyper-accumulation: The finding that lysosomal proteins (like LAMP1) and mitophagy markers increase with age (2-fold in some models) represents a failed compensatory response, not a successful adaptation.

Actionable Insights for Biohackers

-

Prioritize Lysosomal pH: Interventions should focus on acidifying lysosomes, not just “boosting autophagy.”

- Stack: Consider Spermidine (a possible lysosomal activator) alongside exercise.

- Mimetics: Urolithin A is highly relevant here for its specific ability to stimulate mitophagy, but it must be paired with lysosomal support to prevent “trash accumulation.”

-

Exercise Dosing:

- Modality: The study emphasizes chronic endurance/aerobic work (Zone 2) as the primary driver of lysosomal remodeling. Resistance training drives hypertrophy but is less effective at this specific “cleaning” mechanism.

- Volume: Consistency is key. The “clogged drain” clears slowly; sporadic high-intensity bouts may not be sufficient to restore enzymatic pools.

-

Biomarkers to Watch:

- Lipofuscin: Hard to measure directly in vivo without biopsy, but skin accumulation (age spots) can be a proxy for systemic lysosomal health.

Cost-Effectiveness

- ROI: High. Zone 2 cardio is free. The mechanistic benefit (clearing cellular junk) prevents downstream metabolic collapse, which is far more expensive to treat.

- Supplementation: Low-to-Moderate. Basic lysosomal support (fasting/Zone 2) is free. Advanced mimetics (Urolithin A) are expensive ($100+/month) and should only be added if the “free” foundation is solid.

Critical Limitations

- Model Reliance: Much of the mechanistic “clogging” data is derived from rodent models (e.g., specific mouse strains). Human lysosomal kinetics are slower and harder to measure.

- Translation Gap: The “dose” of exercise required to reverse lysosomal pH drift in an 80-year-old human is currently unknown.

- Invasiveness: The gold-standard metrics (lysosomal pH, lipofuscin load) require muscle biopsies, making n=1 tracking difficult for biohackers.

Publication Details:

- Institution: Muscle Health Research Centre, York University, Toronto, Canada.

- Journal: Experimental Physiology (Q2 rank, Impact Factor ~2.8).

- Source: Mitophagy in skeletal muscle: Impact of ageing, exercise and disuse