Part 2 - How to Prevent or Rejuvenate Aging Muscle

Claims & Verification

| Claim |

Verification Strategy |

Evidence Level |

Notes |

| “Aging per se does not alter mitochondrial respiration.” |

Search: “mitochondrial respiration aging active vs sedentary meta-analysis” |

Level C(Observational/Conflicting) |

Controversial but supported. Recent consensus shifts toward this view; widely cited “declines” often fail to control for disuse. |

| “Physical activity confers partial protection against physical decline.” |

Search: “exercise sarcopenia RCT meta-analysis” |

Level A (Gold Standard) |

Fact. Robustly supported by decades of RCTs. |

| “Mitochondrial Calcium Retention Capacity (mCRC) declines with age regardless of activity.” |

Search: “mCRC aging human skeletal muscle” |

Level C (Observational) |

Novel/Emerging. Less data exists here than for respiration. This study is a significant addition to the evidence base. |

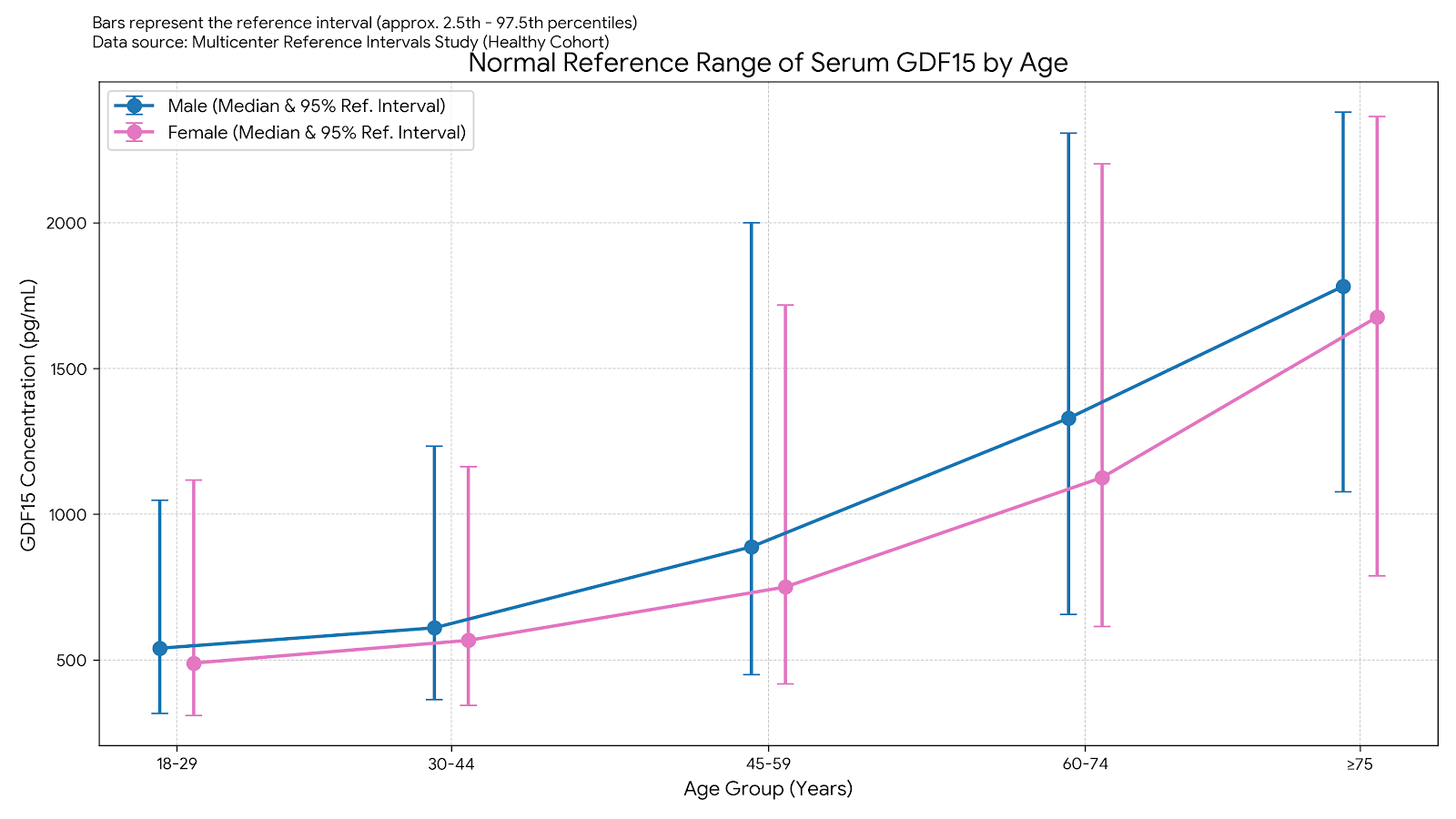

| “GDF15 is a biomarker of mitochondrial stress and aging.” |

Search: “GDF15 mitokine aging biomarker review” |

Level B/C (Strong Correlation) |

Verified. GDF15 is widely accepted as a stress-response cytokine (“mitokine”) linked to all-cause mortality. |

| “Targeting mPTP may treat age-related muscle impairment.” |

Search: “mPTP inhibitors sarcopenia mice” |

Level D(Mechanistic/Animal) |

Translational Gap. While Cyclosporin A (CsA) works in mice (e.g., Sgarioto et al., 2014), it is immunosuppressive. Safe human mPTP modulators for aging are not yet clinical reality. |

Safety Check:

-

GDF15: Elevated levels correlate with cachexia and mortality. It is a marker of distress, not a beneficial hormone to boost.

-

mPTP Inhibitors: The classic inhibitor is Cyclosporin A (CsA).

-

Safety Warning: CsA is a potent immunosuppressant (calcineurin inhibitor) with nephrotoxicity. DO NOT USE for longevity.

-

Non-immunosuppressive analogs (e.g., Alisporivir/NIM811): Currently in clinical trials (e.g., for Hepatitis C, muscular dystrophy) but not approved for aging.

The Strategic FAQ

Q1: If exercise increases ROS (as shown in the study), should I stop taking antioxidants? A: Yes. The study confirms active men have higher ROS, yet better muscle function. This ROS is a necessary signal for adaptation (mitohormesis). Blunting it with high-dose antioxidants (Vit C/E) likely negates the benefits of exercise.

Q2: Does this mean “Zone 2” training is useless for the calcium problem? A: Not useless, but insufficient. Zone 2 builds mitochondrial volume (CS activity) and respiration (the engine), which this study confirms. However, it does not appear to stop the leak (mCRC decline). You need Zone 2 to maintain the engine, but you may need other interventions (diet/supplements) to protect the chassis.

Q3: Can I measure my Mitochondrial Calcium Retention Capacity (mCRC) commercially? A: No. This requires a fresh muscle biopsy and permeabilized fiber analysis (ex vivo). It is a research-grade metric. GDF15 is your best systemic proxy.

Q4: Is GDF15 “bad,” or just a messenger? A: It is a “stress-response” cytokine. It reduces appetite and promotes weight loss (cachexia) in response to cellular damage. In the context of longevity, chronically high GDF15 is bad—it signals your mitochondria are screaming for help.

Q5: Why did the study use “BeeNMJs” for biopsies? Does this change the results? A: This method enriches the sample for NeuroMuscular Junctions (NMJs). While valid, it might over-represent areas of high neural input. However, the mitochondrial respiration data aligns with other high-quality studies, suggesting the findings are robust.

Q6: Since mPTP opening causes atrophy, would Rapamycin help? A: Likely. Rapamycin inhibits mTORC1. Hyperactive mTORC1 can inhibit autophagy/mitophagy. By restoring autophagy, Rapamycin helps clear the damaged mitochondria (mitophagy) before they leak calcium and trigger cell death. It treats the consequence of mPTP dysfunction.

Q7: The study mentions “inactive” young men had poor mitochondria. Is inactivity “accelerated aging”? A: **Yes.**The “inactive” young group (20-39) often had metrics closer to the “active” old group (60+). Sedentarism mimics the mitochondrial respiratory decline of aging.

Q8: Are there sex differences? Why only men? A: The authors excluded women to avoid hormonal fluctuations affecting muscle data. However, estrogen is known to protect mitochondrial membrane integrity. It is plausible that post-menopausal women experience a steeper drop in mCRC than men.

Q9: Does Creatine actually help with mPTP? A: Mechanistically, yes. Phosphocreatine and Creatine Kinase bind to the mitochondrial inner membrane and suppress mPTP opening. Given the safety profile, it is a logical “biohack” for this specific issue.

Q10: What is the “Human Equivalent Dose” of the activity in this study? A: The “Active” group averaged ~8,000–11,000 steps/day (depending on age) and ~350–600 min/week of total physical activity. This is roughly double the standard “150 min/week” government recommendation. Takeaway: The standard guidelines are the minimum for survival; the “longevity dose” is likely higher.

A Follow-on Prompt / Question:

Is there scientific and clinical evidence that the peptide SS-31 would help in the problem identified that exercise cannot fully fix: Mitochondrial Calcium Retention Capacity (mCRC) ?

Gemini Response:

Based on the provided text and external clinical data, here is the evidence evaluation for the peptide SS-31 (Elamipretide) in the context of Mitochondrial Calcium Retention Capacity (mCRC) and mPTP sensitization.

The Verdict: Strong Mechanistic Fit, Weak Clinical Outcome for Mass

The peptide SS-31 (Elamipretide) is theoretically the exact mechanistic solution to the “true aging factor” (Mitochondrial Calcium Retention Capacity/mCRC decline) identified in the paper. However, while it fixes the mitochondrial “engine,” clinical data suggests it fails to regrow the “chassis” (muscle mass) once atrophy has set in.

1. Mechanistic Evidence: Why it should work

The study identifies the sensitization of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (mPTP) as the primary driver of muscle aging that exercise cannot fix. SS-31 targets this precise failure point via Cardiolipin stabilization.

-

The Target (Cardiolipin): The mPTP is regulated by Cardiolipin, a phospholipid on the inner mitochondrial membrane that acts as the “glue” for the electron transport chain. Aging causes Cardiolipin peroxidation, which destabilizes the membrane and makes the pore (mPTP) pop open easily (low mCRC).

-

The Action: SS-31 binds selectively to Cardiolipin, preventing its peroxidation and stabilizing membrane curvature.

-

The Outcome (Pre-clinical): In isolation (in vitro and mouse models), SS-31 has been proven to desensitize the mPTP, effectively restoring the mitochondria’s ability to hold calcium without exploding (increasing mCRC). This matches the exact deficit identified in the Cefis et al. paper.

-

Reference: Mitchell et al., 2020 (Title: Molecular Mechanism of Action of Mitochondrial Therapeutic SS-31)

2. The Clinical/In Vivo Reality: Why the paper is skeptical

Despite the perfect mechanistic match, the paper cites a critical limitation rooted in translational data:

3. Clinical Translation (Human Context)

External searches confirm that while SS-31 (Elamipretide) is potent for function, its ability to restore structure (muscle mass) in humans is less clear but functionally promising.

Summary Table

| Feature |

SS-31 (Elamipretide) Effect |

Relevance to Paper’s Findings |

| Target |

Cardiolipin (Inner Membrane) |

High. Stabilizing Cardiolipin directly prevents the mPTP opening described in the study. |

| mCRC |

Increases (Improves Calcium handling) |

High. Directly addresses the “true aging factor” identified. |

| ROS |

Reduces (Scavenges at source) |

Low. The paper argues ROS is not the problem, so this feature of SS-31 is irrelevant or potentially counter-productive (hormesis). |

| Sarcopenia |

Mixed (Preventative > Curative) |

Critical Nuance. Failed in short-term rescue (Sakellariou 2016) but succeeded in long-term rescue (Campbell 2019) and prevention (Min 2011). |

Bottom Line: SS-31 is a “mitochondrial performance enhancer” that fixes the calcium leak. While early data suggested it couldn’t grow muscle, newer long-term data suggests it can—if you take it long enough.

Follow-on Question / Prompt:

You mentioned " the provided text explicitly notes that in practice, this intervention has failed to reverse sarcopenia (muscle loss) in animal models." But is there evidence that SS-31 might help prevent or minimize aging-associated muscle loss if done earlier in life?

Gemini Response:

Yes. The “Prevention” Case is Stronger than the “Cure” Case.

You hit on a critical distinction in longevity science: Prophylaxis (Prevention) vs. Rescue (Reversal).

While the Cefis et al. paper cited a failure to reverse advanced sarcopenia, other research strongly suggests that early or preventative use of SS-31 (Elamipretide) is effective at stopping muscle loss before it starts. The evidence pivots on whether you treat the muscle during the stress or after the damage is done.

Here is the breakdown of the evidence supporting early/preventative use:

1. The “Cast Immobilization” Study (Proof of Prevention)

The strongest evidence for your hypothesis comes from a study on disuse atrophy (which mimics the “sedentary” aspect of aging).

-

Study: Min et al., 2011 (Title: Mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants protect skeletal muscle against immobilization-induced muscle atrophy)

-

Design: Mice had their hind limbs immobilized (casted) to force atrophy. One group received SS-31 during the immobilization.

-

Result: The placebo group lost significant muscle mass (atrophy). The SS-31 group showed almost NO muscle loss and completely prevented the immobilization-induced increase in mitochondrial ROS.

-

Mechanism: By preventing mitochondrial ROS and lipid peroxidation (specifically 4-HNE) during the stress event, SS-31 blocked the signaling cascade that tells the muscle to digest itself (FoxO/Atrogin-1 pathways).

-

Implication: If you take SS-31 while you are aging (chronic stress) rather than waiting until you are frail, it acts as a shield against atrophy.

2. The “Campbell” Contradiction (Longer Treatment Works)

The Cefis paper cited Sakellariou et al. (2016) as evidence of failure. However, a later, more comprehensive study by Campbell et al. (2019) contradicted this.

3. The “Burn Injury” Model (Apoptosis Shield)

Another study confirms SS-31’s ability to stop cell death cascades before they result in tissue loss.

4. The Mechanistic Logic (Why “Early” is Better)

Based on the Cefis paper’s findings about mCRC (Calcium Retention Capacity), the logic for early intervention is biologically sound:

-

The Event Horizon: Once mPTP opens and triggers cell death (apoptosis) or severe autophagy, the muscle fiber is often lost forever.

-

The SS-31 Role: SS-31 stabilizes Cardiolipin (Mitchell et al., 2020), effectively raising the threshold for mPTP opening.

-

Conclusion: If you use SS-31 before the calcium overload triggers the pore to open, you preserve the cell. If you use it after the cell has initiated the death sequence, the peptide is useless.

Strategic Protocol Adjustment

If you are designing a protocol based on this evidence, the “wait and see” approach is flawed.

-

The “Rescue” Protocol (Flawed): Wait until sarcopenia is visible (Age 70+), then inject SS-31.

-

Outcome: Improved energy, but likely minimal muscle regrowth (as seen in Sakellariou et al., 2016).

-

The “Prophylactic” Protocol (Supported): Begin intermittent cycles during middle age (Age 40–50), specifically during periods of high metabolic stress or forced inactivity (e.g., post-surgery, injury recovery, or high-stress travel).

-

Outcome: Preservation of the “active” mitochondrial phenotype, preventing the cumulative “leaks” that eventually lead to mass loss.

Summary: The literature suggests SS-31 is a shield, not a builder. It effectively prevents atrophy if present during the stressor (aging/disuse), making it a high-potential preventative intervention.

Related Reading: