Prior to 2009 the consensus of scholars was that aging could not be treated or if it could be it must be a youth factor (e.g., growth hormone). Numerous advertised non-scientific approaches that absconded with a lot of folk’s money mostly confused people and were counterproductive for the field. However, there were two scientific settings in which aging could be reproducibly delayed. Unfortunately, neither was optimal for use in people. They were restrictions of diet and/or growth factors by genetic means. Since people do not like restricting anything, especially food, progress toward a deeper understanding of aging and potential ways to delay its effects was slow.

In recognition of this bottleneck, the National Institute of Aging did a smart thing. It established a program to identify compounds that could be tested for aging effects under rigorous and standard conditions. The goal was to determine drug effects on lifespan of genetically heterogeneous mice of both sexes. A major advantage of this new Intervention Testing Program is that the three test sites are geographically separated, the test mice are by design genetically heterogeneous and included both sexes and importantly, the site directors are recognized experts in aging studies in rodents but had no stake in the outcomes. More information about the ITP can be found here.1

It has been exceptionally successful. To date, the ITP website indicates they have tested or in the process of testing 64 different compounds, some at varied doses and in combination. Twenty publications from the ITP have reported increases in lifespan from ten compounds. Importantly, the ITP also reports compounds that do not extend lifespan.

In this section, we focus of the ITP 2009 test of what was then an unlikely candidate drug called rapamycin. Results showing increased median and maximum lifespan in advanced aged males and females in this paper reset the paradigm for aging studies. It suggested that pharmacological agents can prevent, delay and/or reduced the severity of age-caused morbidities. In this lifespan, we will first briefly remind readers about the biology of the cell systems affected by rapamycin, better known as the targets of rapamycin or TOR. Next, we will review the results of several studies on the effects chronic rapamycin has on lifespan in both sexes including our recollection of the first study (Harrison et al., 2009). Following that, we will relate selected examples of the effects chronic rapamycin has on age-caused diseases. We conclude with our view of what rapamycin effects are telling us about aging and how it might be working. We confess at the outset that we have only a faint picture of rapamycin’s function as an anti-aging agent and suggest that it will be as complicated and mysterious as the studies to determine how restriction of food and growth factors work, which after half a century still have a way to go.

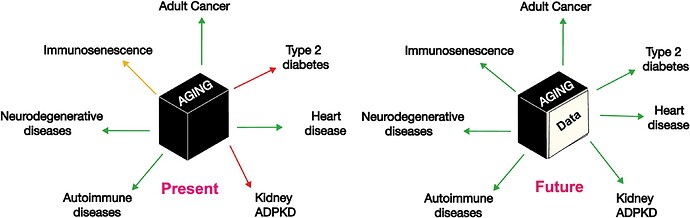

Rapamycin Today and in the Future:

Rapamycin has variable effects on these diseases. The left panel shows some that it helps (green arrows) and others it hurts (red arrows). It appears to have both good and (not so) bad effects on the immune system (gold arrow) and might be better termed an immune modulator (Kolosova et al., 2013). This indicates that, while rapamycin might be an effective approach for translational gerontology, each patient will need to be evaluated considering these differential effects.