That article mentions losartan as reversing damage in mice. Here’s another comparison between losartan and telmisartan:

PAPER FROM INDIA ![]()

Blood pressure-lowering effect of telmisartan compared to losartan among mild to moderate essential hypertensive adult subjects: A meta-analysis

When I went to the hospital back in September they prescribed me Amlodipine (tiny little flat pills). My blood pressure fell to where a few times it was 110 over 68 or so (they prescribed it I think to prevent complications in the brain). That’s pretty good! Usually my bp is around 125 over 80 or a little more.

…

One thing that has occurred to me is how people talk about bp. They talk about it like people are being lazy or lacking in morals or something if it’s like 140 over 85 or so. In many cases, that might be the median BP in some parts of the world, or at least the upper third of the population. Who’s to say that isn’t the typical BP of our ancient ancestors that made it to that age?

What I’m getting at is that there’s a kind normative language about the right bp level. I think the more ethical way to talk about bp is that medicines are artificially keeping it low. What we’re doing is more akin to applying life-extension methods than being an upright, decent human being.

Untreated, my blood pressure is low. Every time I’ve tried a -flozin it has given me a headache and made me feel light headed and out of it for 1-2 days.

I’ve tried eating extra salt and drinking lots of water, but haven’t found a solution, so no -flozins for me.

Hunter gatherers had/have a diet low in salt and high in potassium, they were physically very active and lean. Their BP was most likely low.

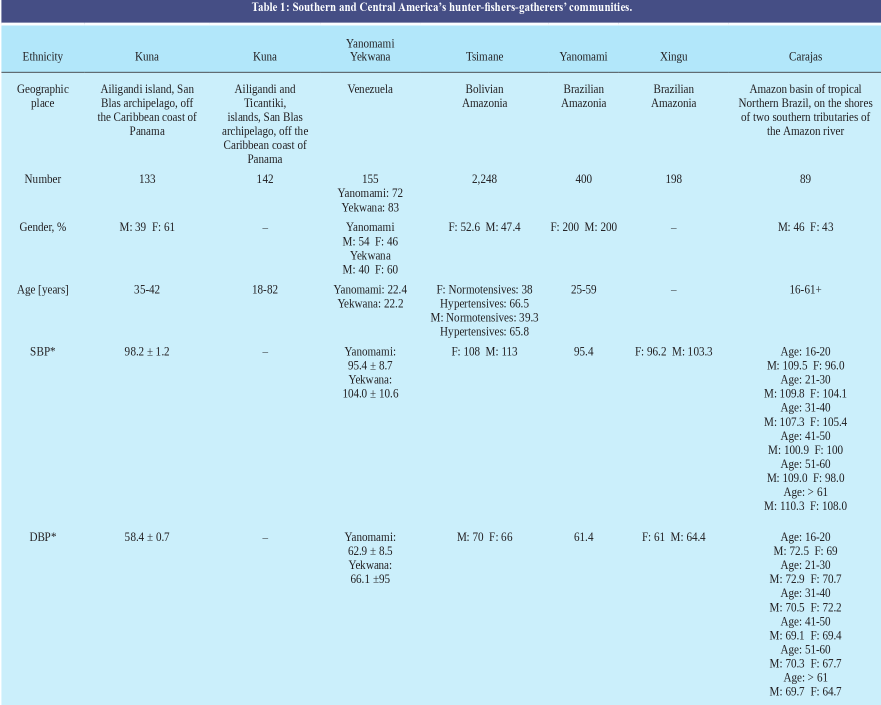

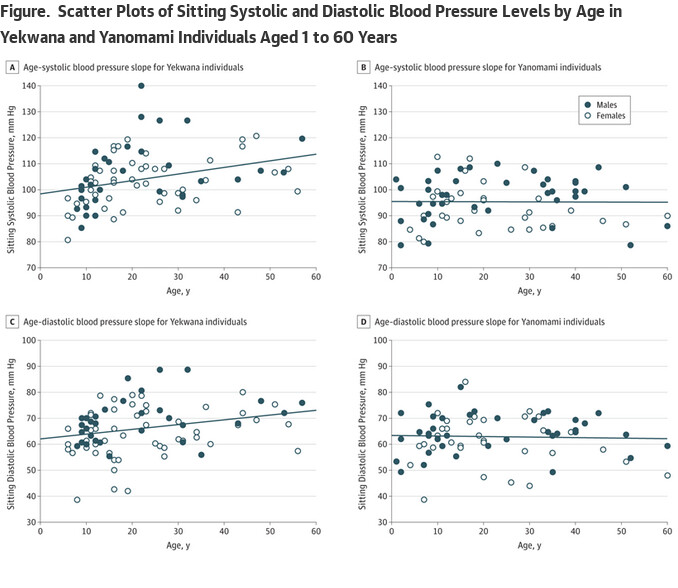

I was familiar with only the Yanomami but here’s a review of other hunter-gatherers in South/Central America, all had 95/65 BP with hypertension (>140) at 0-2% prevalence.

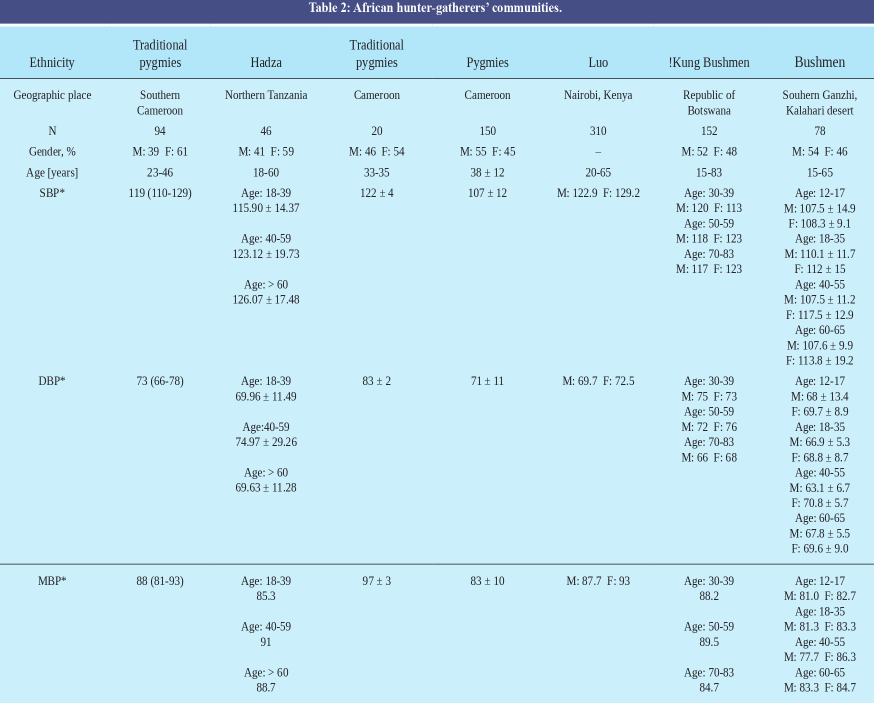

African hunter-gatherers data ~120/80 hypertension 0-2% (Hadza higher with age):

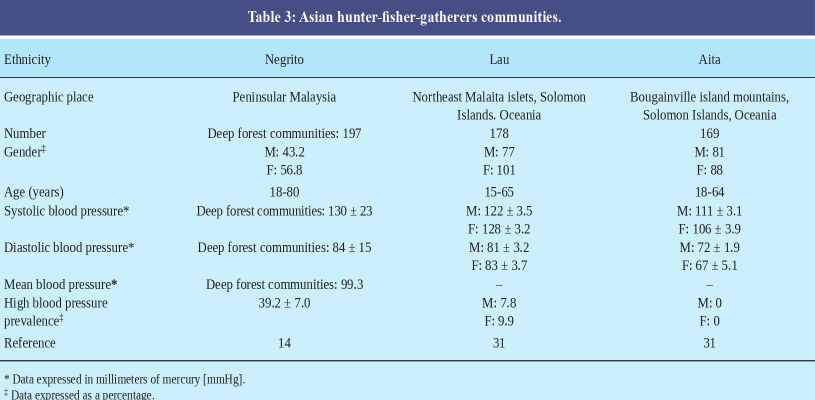

Asian fish-hunter-gatherers:

Those are interesting numbers, though according to this:

According to statistics, more than 75% of adults over 65 have high blood pressure.

Adults between the ages of 55-64 are also at-risk, with 70 percent of men and 63 percent of women meeting the standard.

Here, “high blood pressure” means:

A normal blood pressure is lower than 120/80. Once your blood pressure reaches 130/80 or higher, you meet the definition of high blood pressure.

Why does blood pressure rise like that with age?:

This happens because our arteries, which carry blood from our hearts, change over time. They become stiffer, which can result in higher blood pressure.

So, do hunter gatherers not experience this? I’d guess that they do. It’s possible the ones who would have pushed the stats higher died young, so didn’t get counted. And the ones that lived to age 65, say, were exceptionally hardy (able to battle germs and bacteria and other things that tend to kill others in their tribe).

If it’s because of survivorship bias, wouldn’t there should be a spike in BP with age, as it takes time for it to cause damage, especially without other risk factors? An inverted U-shape curve.

If that’s the case, is the age related data in the tables and another one from Yanomami in the paper showing it’s stable and without bias?

Maybe so. It’s just a little hard to believe that the lifestyle and diet of hunter gatherers could delay the rise in blood pressure that we see in the U.S. – the percentages of Americans with much higher blood pressure just seem too high. And for even older Americans (like age 80+), targets for bp are like 150 over 90. Could that really all just be due to the cumulative effect of not adopting a hunter gather lifestyle?

One thing about the “normative language” I wrote earlier that didn’t occur to me was that a lot of the talk about keeping the numbers so low (like 110 and lower) is likely mainly directed at people under about the age of 55, or even 50. Once one is past an age like that the targets and standards shift.

I’m open to the possibility that the data is biased, or wrong in some other way.

If this was a cohort study, rather than a cross sectional one, should resolve the bias question, if my memory serves me correctly. At the same time it seems odd that the people with hypertension would die, or is that not the implication?

@relaxedmeatball is there any consensus about whether age related increases in hypertension is because of lifestyle (salt, adiposity , activity levels) or aging? If the latter, what’s the consensus related to hunter-gatherer data on HBP levels with age?

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/fullarticle/2713959

An updated optimal BP level and medication level survey:

What are the optimal BP level that you are currently aiming, with what medications at what dose and why? Everyone please chime in.

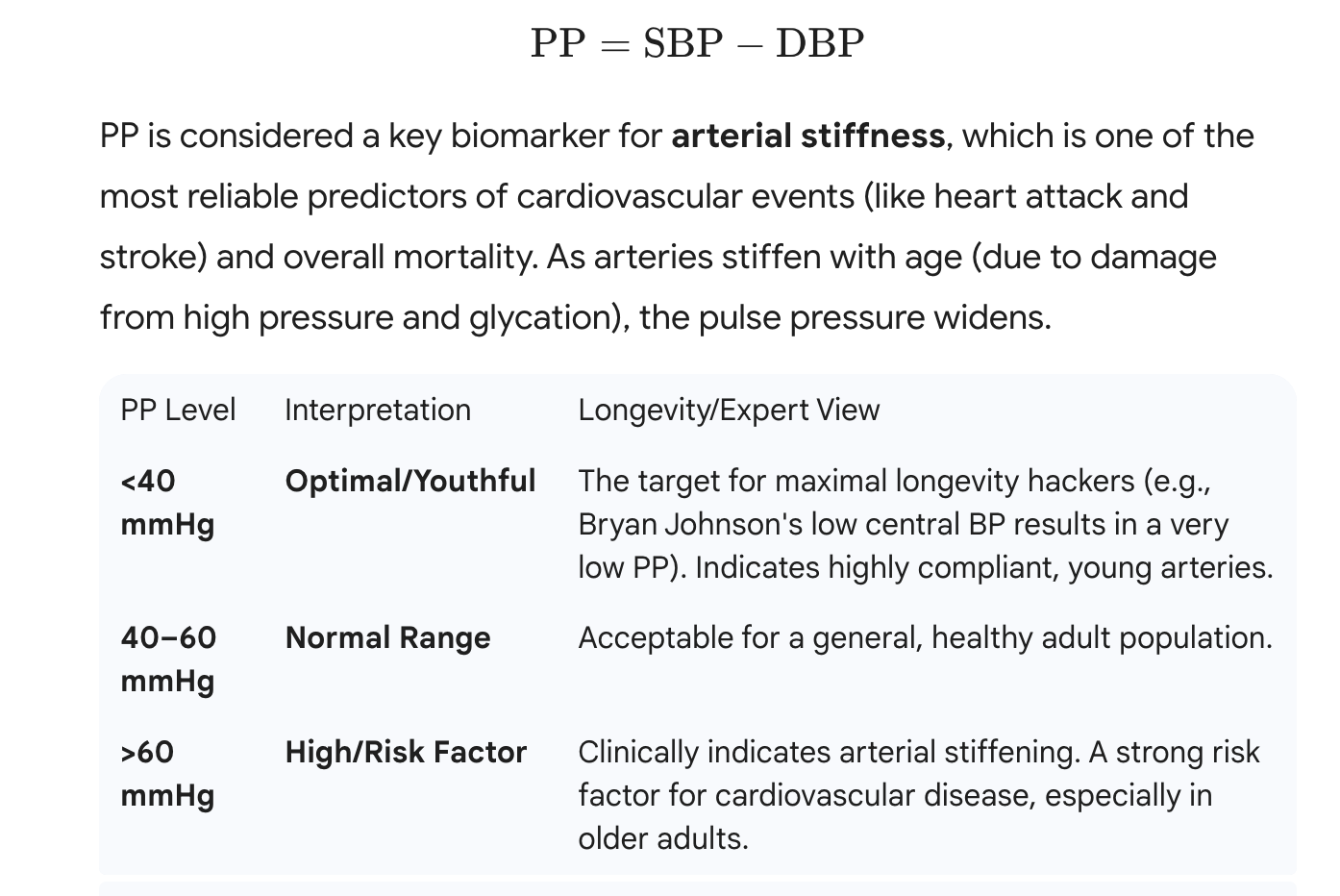

Additionally, some Pulse Pressure Info:

My BP meds is telmisartan of 80mg. Sometimes I add 5mg Amlodipine.

My BP is usually around 110/70. Sometimes lower but no dizziness with it.

Peter Diamandis is on Losartan.

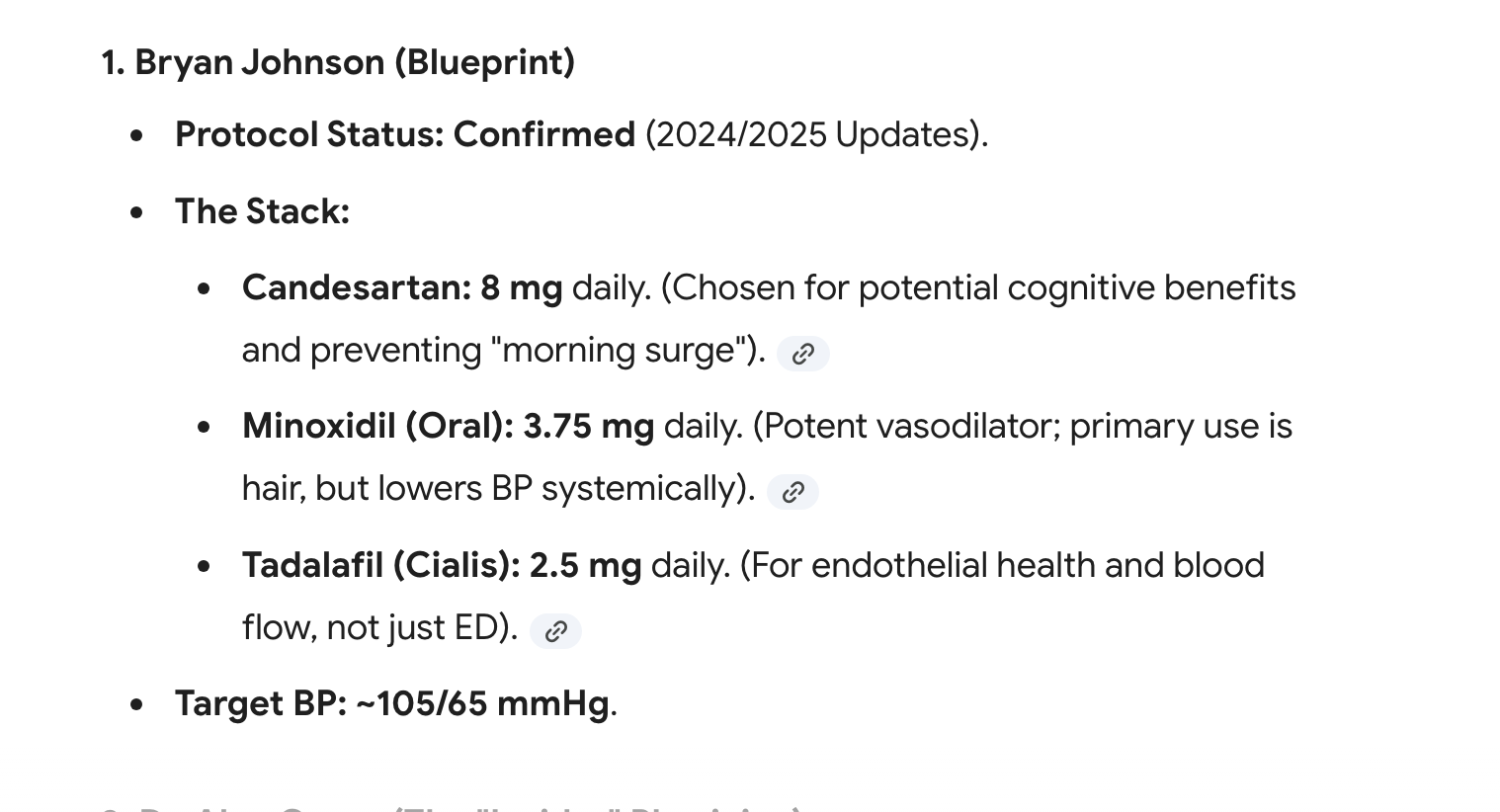

Brian Johnson is on Candesartan 8 mg. It is equivalent of 50 mg Losartan and 40 mg Telmisartan (need fact checked).

Longevity experts and biohackers target optimal blood pressure around 110-120 systolic / 70-80 diastolic mmHg (or lower if tolerated), viewing standard “normal” ranges (120-129 systolic) as suboptimal for maximizing lifespan.

-

Peter Attia (longevity physician): Recommends targeting <120/80 mmHg (often <120 systolic, without symptoms like lightheadedness), based on the SPRINT trial showing major reductions in CVD, stroke, and mortality risk.

-

Bryan Johnson (Blueprint protocol): Personally achieves exceptionally low BP (brachial ~114/76 mmHg previously reported; recent biomarkers place it lower than 90% of 18-year-olds), using therapeutics like candesartan for cardiovascular protection equivalent to a much younger age.

-

Valter Longo (fasting researcher): Observes fasting-mimicking diets can substantially lower systolic BP (e.g., drops of 4-20 mmHg in studies, such as from 140 to 120 mmHg in clinical cases), supporting periodic cycles for reduced cardiovascular risk factors.

Supported by longevity studies (e.g., SPRINT extensions) showing lowest CVD/mortality risk below 120 systolic, with benefits extending lifespan.

Here is confirmed report on BJ

A large study in rural China published in Nature Medicine showed that blood pressure below 130/80 mm Hg (millimeters of mercury) not only lowered the risk of dementia, but also reduced cognitive impairment by 16%. High blood pressure, also known as hypertension, can damage small blood vessels in the brain, and is associated with cognitive decline and memory problems. This study is the first to definitively show that lowering blood pressure to these levels can truly decrease the likelihood of dementia.

This, says Christopher Howes, MD, a Yale Medicine cardiologist, is important not only because high blood pressure is associated with many other health conditions, but because there are few proven ways to reduce the risk of dementia.

“We have some medicines that can maybe slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, but we don’t have many ways to prevent dementia,” he says. “Now we have this real objective data that shows people who had high blood pressure and were on therapy for it have a lessened likelihood of dementia.”

Plus, high blood pressure is an important risk factor for coronary artery disease, Dr. Howes adds. “Treating high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol levels are two cornerstones to cardiovascular health, he says. “We have effective medications for both conditions. We need to work aggressively with our patients to achieve the desired target levels.”

The only device I know of that has clinical validation of PWV measurement are the Withing scales. Been tracking mine for 5 years now. Mine is lower than 80% of people in my age group using this scale and it has been continually improving for the past 3 years. That’s the time frame of my addition of manganese to my Vit stack. BUT there is a confounder as I started GLP1’s 2 years ago and lost 55lb, which probably provides a stronger effect. But who knows, there may be a synergy?

Look up manganese, it may help to reduce arterial plaque Just do not over do it as it has an Inverted U-shaped dose–response : Outcome improves as dose rises up to a peak, then worsens as the dose increases further and with manganese it can become harmful at higher doses.

Also I’ve been keeping my BP around 100/65 for the past year and no dizziness.

clinical validation of PWV measurement are the Wit (1).pdf (346.6 KB)

Yeah, I gave up on that other thing and got a withings scale. Very fancy, but I admit I haven’t read that much about it so thanks for the post.

Question about a high reading on Omron

We have a cuff but I rarely use it because my BP has historically been low to, more recently, just very good

This morning, I have taken 5 readings and they are all really high.

122-127 over 80-81

This has never happened.

My biggest question is it normal to just have bad days every once in a while, or is this something that should concern me (I’m a bit concerned).

Of course I’ll do this daily now to see if it’s a trend, but in the meantime??

Edit 1:

I’m down to 115/79 now, so it’s a lot better… but still a bit high for me. So maybe this was just a fleeting thing?

Edit 2:

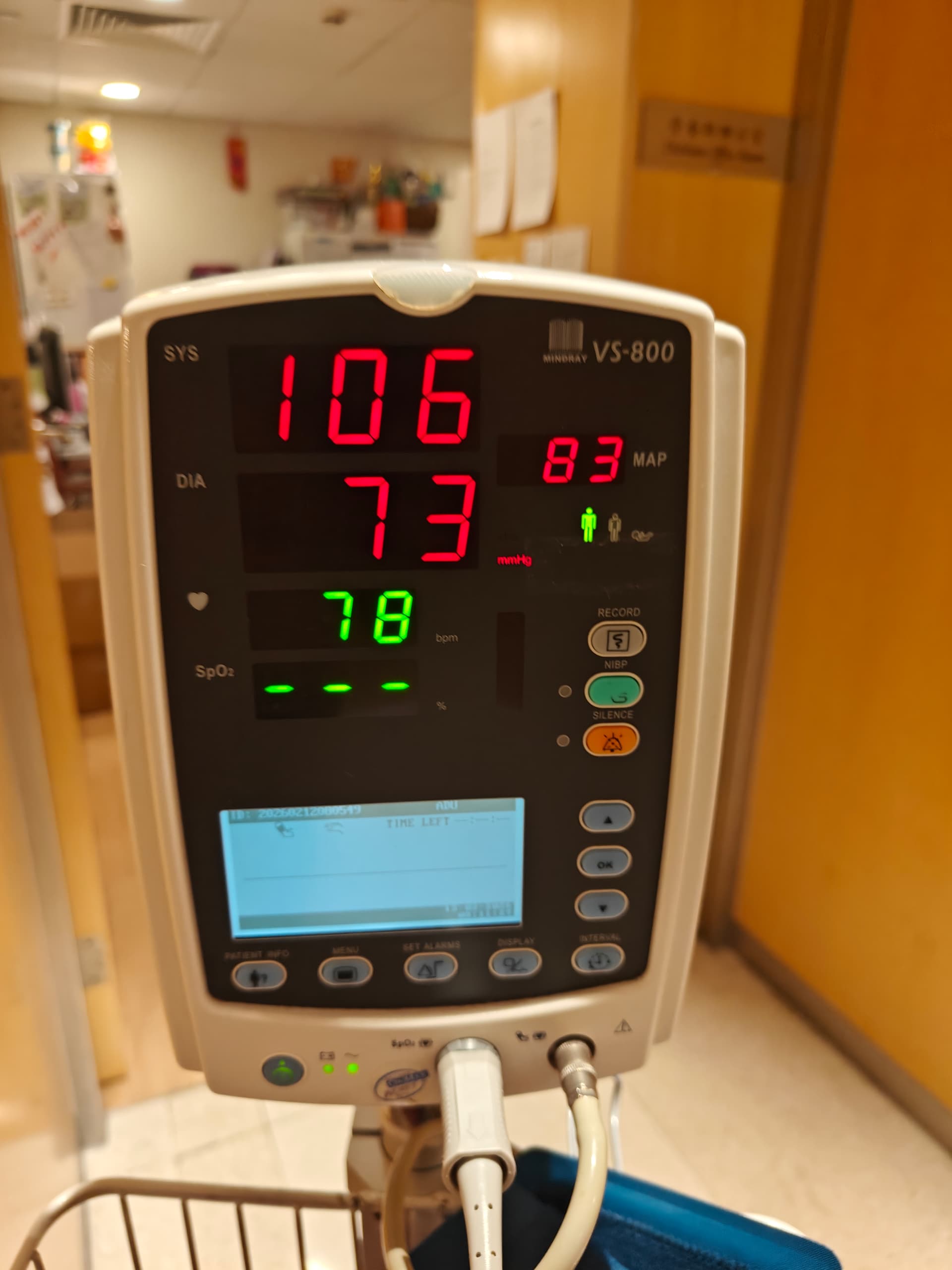

I’m back down to 105/73… so I guess this was much ado about nothing… first time I have seen those numbers, even at a doctor’s office, so I panicked!

Carry on… nothing to see here…

Higher blood pressure is associated with higher handgrip strength in the oldest old

Results: In middle-aged subjects, BP and handgrip strength were not statistically significantly associated. In oldest old subjects, higher systolic BP (SBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and pulse pressure (PP) were associated with higher handgrip strength after adjusting for comorbidity and medication use (all P < 0.02). Furthermore, in oldest old subjects, changes in SBP, MAP, and PP after 4 years was associated with declining handgrip strength (all, P < 0.05).

Conclusion: In oldest old, higher BP is associated with better muscle strength. Further study is necessary to investigate whether BP is a potential modifiable risk factor for prevention of age-associated decline in muscle strength.

Perhaps it’s due to something like this: older people with bad arteries require higher pressure to supply muscle with adequate blood. Old people with low pressure might be of two main types – those with good arteries and those with bad. Those with good arteries can remain relatively strong using low blood pressure; but those with poor arteries will lose strength when pressure is low.

Could also be survivorship bias.

Oh, one thing I forgot to mention: Andrea Maier is a coauthor (researchers from Leiden University medical center). This must have been one of her early papers, as it was published in 2011 (I think she’s in her mid to late 40s in age, so it would have been completed in her late 20s to early 30s).

I would like to look at the whole paper and whether the relationship is linear. The association is only among old people and even more so among the “oldest old subjects” so it might be that a subgroup of frail people with hypotension creates that relationship while the relationship doesn’t exist among those with normal or high BP.

They show a bar chart with grip strength versus blood pressure with pressure broken down into tertiles – “lowest tertile”, “medium tertile”, and “highest tertil”. Grip strength increases from lowest to medium to highest tertiles, but it’s not enough information to see that the trend is linear.

They offer a suggestion as to the cause of the relationship in the paper:

How can we explain the associations between higher BP and better muscular function in the oldest old? Peripheral vascular resistance increases with chronological age due to a reduced sympatholysis, which results in an elevated sympathetic tone.[31] [32] Second, morphological changes to the arteriolar network contribute to higher vascular resistance.[8] Third, aging is associated with a reduced capacity in vasodilation caused by changes in endothelium-dependent pathways in animal models.[33]–[36] Maybe increased vascular resistance during the aging process requires higher pressure as a mechanism to maintain tissue perfusion as a means to prevent further ischemic end organ damage in kidney, brain, and skeletal muscle. Another cause for higher BP in elderly could be the age-associated increase in cortisol levels.[37], [38] But as higher cortisol levels associate with lower handgrip strength, this does not explain our finding of higher handgrip strength.[38]