For decades, the “Goldilocks” rule of sleep—neither too little nor too much—has dominated longevity discourse. Deviating from the seven-to-eight-hour window has consistently correlated with premature death. However, a robust longitudinal analysis published in GeroScience by researchers at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain, suggests we have been looking at the equation in isolation. The study, utilizing the Seniors-ENRICA-1 and 2 cohorts, reveals that physical activity, “PA” acts as a powerful biological buffer, potentially neutralizing the lethal effects of suboptimal sleep.

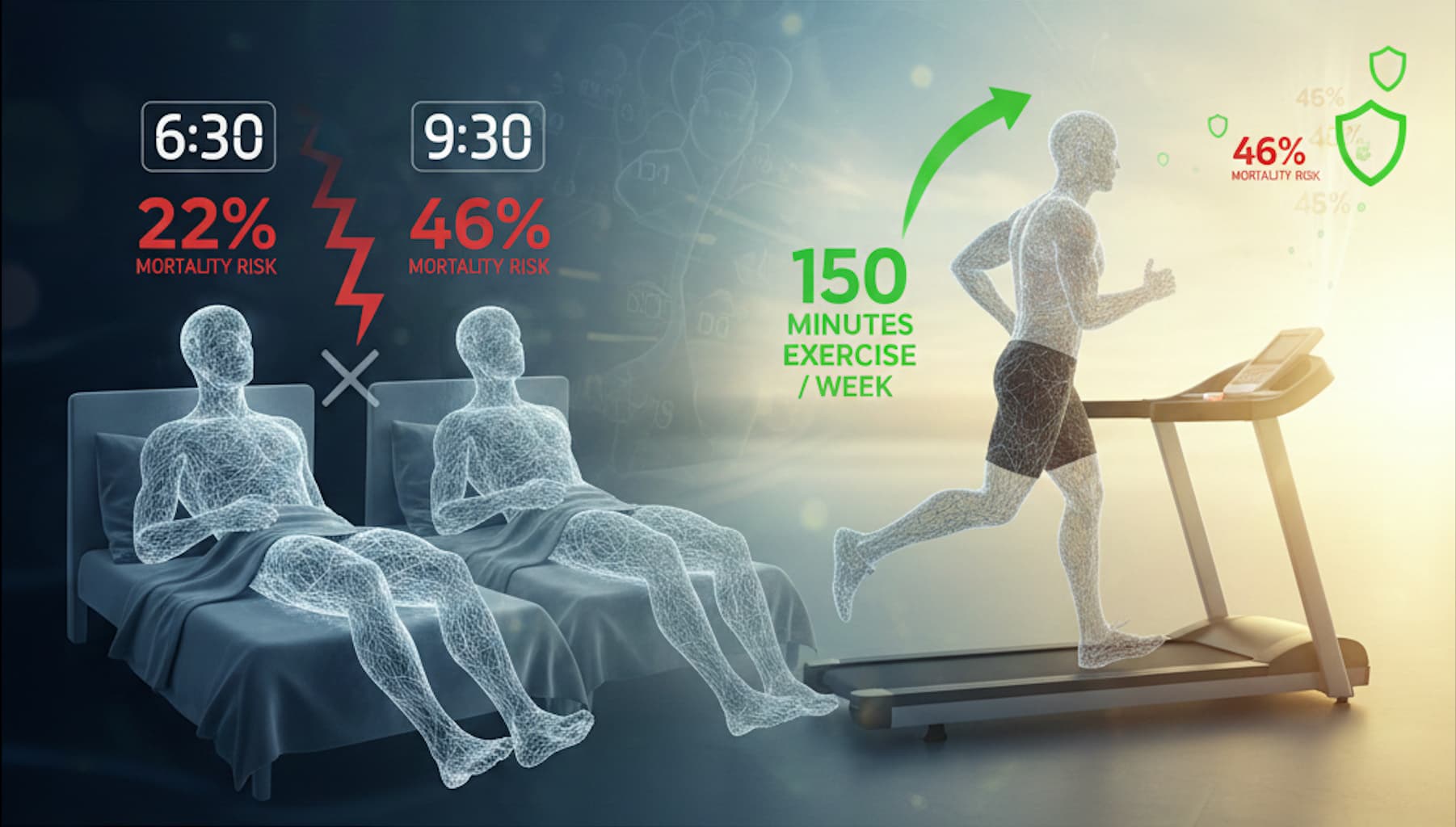

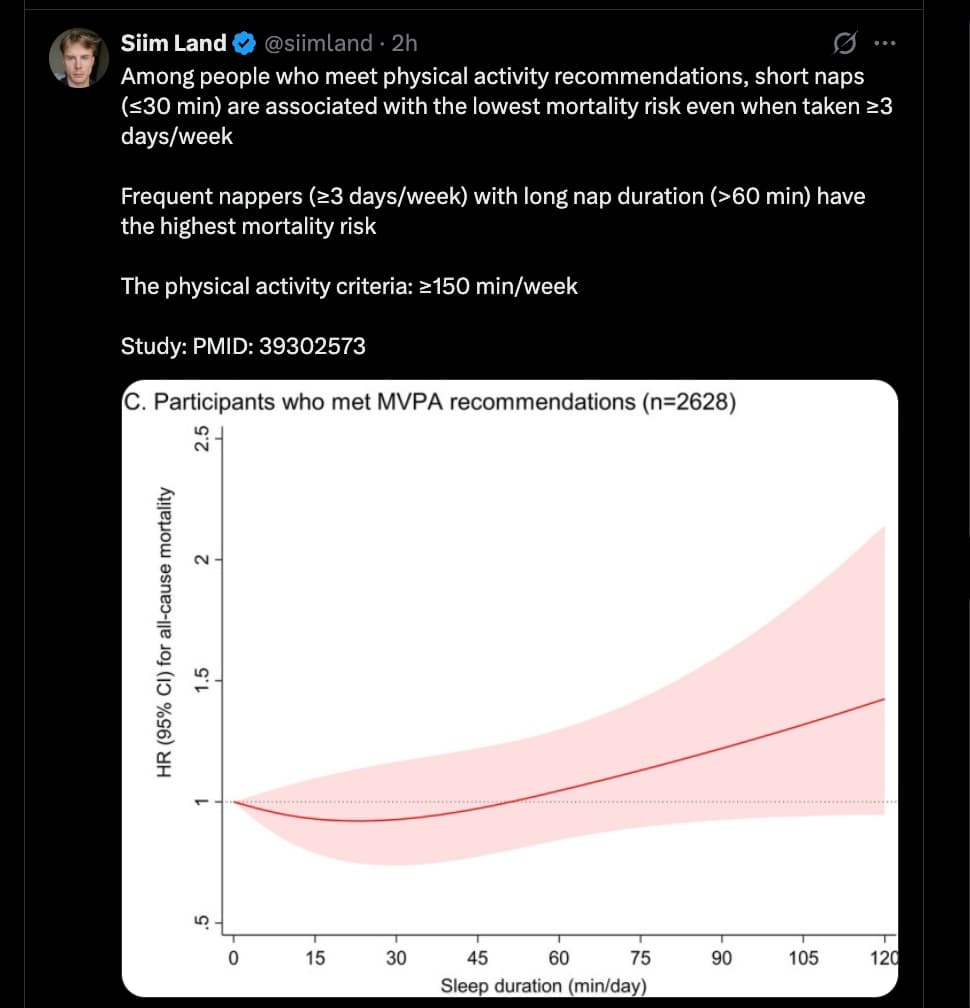

The researchers tracked 6,791 older adults (mean age ~70) for over a decade, analyzing the interplay between nighttime sleep duration, midday napping, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). The findings were stark: for sedentary individuals, sleeping less than seven hours or more than eight hours increased mortality risk by 22% and 46%, respectively. Yet, for those meeting the WHO-recommended 150 minutes of weekly MVPA, these risks virtually vanished. The “U-shaped” mortality curve typically associated with sleep duration flattened entirely in the active group, suggesting that exercise may compensate for the systemic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation triggered by poor sleep.

Midday napping—a cultural staple in Spain—presented its own nuances. While “siestas” under 30 minutes were associated with an 17% reduction in mortality (likely due to blood pressure lowering), “very long” naps exceeding 60 minutes were linked to a 32% increased risk among the inactive. Again, this risk was mitigated in those who exercised. This implies that long naps in sedentary populations are likely markers of underlying frailty or “inflammaging” rather than restorative rest. For the biohacker, the takeaway is clear: if your sleep hygiene is compromised, your exercise volume is your primary insurance policy.

Source:

- Open Access Paper: Associations of nighttime sleep, midday napping, and physical activity with all-cause mortality in older adults: the Seniors-ENRICA cohorts

- Journal: Geroscience, Date; 2025 Apr

- Impact Evaluation: The impact score of this journal is 5.4 (Impact Factor 2024), evaluated against a typical high-end range of 0–60+ for top general science (e.g., Nature or Science), therefore this is a High impact journal within the specialized field of Geriatrics and Gerontology, where it ranks in the top quartile (Q1).

Mechanistic Deep Dive:

- Vascular Health & cGAS-STING: Sleep deprivation is known to increase cytosolic DNA leakage, activating the cGAS-STING pathway (2025), which drives vascular “inflammaging” and endothelial dysfunction. MVPA promotes laminar shear stress, which suppresses this pro-inflammatory signaling.

- Autophagy & mTOR: Exercise induces systemic autophagy, potentially “cleaning up” the cellular debris and metabolic byproducts (like adenosine and misfolded proteins) that accumulate during poor sleep cycles.

- Metabolic Clearing: Physical activity improves insulin sensitivity, countering the glucose intolerance typically induced by short sleep Sleep duration and metabolic health (2010).

Novelty: This paper provides rare evidence of an interaction effect, proving that sleep-related mortality is not an absolute constant but is contingent on metabolic and physical status. It shifts the focus from “Sleep Hygiene” alone to “24-Hour Movement Guidelines.”

Critical Limitations:

- Self-Reporting Bias: Sleep and nap durations were self-reported, not measured via polysomnography or actigraphy, introducing “recall bias.”

- Reverse Causality: Long napping (>60 min) may be a symptom of existing subclinical disease (e.g., undiagnosed heart failure or sleep apnea) rather than the cause of death.

- Translational Uncertainty: While the cohort is large, it is ethnically homogeneous (Spanish/Mediterranean), potentially limiting generalizability to populations with different circadian genetics or dietary backgrounds.