I am not sure alcohol lowers fasting blood glucose levels. It will lower glucose levels when it is in the system, but you are not in a fasted state then.

Summary: A systematic review and meta-analysis explored whether alcohol consumption influences androgenetic alopecia (AGA), the most common form of hair loss. The study found a modest association between drinking and AGA, with drinkers 1.4 times more likely to experience AGA than non-drinkers, though the link was not statistically significant.

FYI it’s ok to have a drink on Thanksgiving, especially if democrats are republicans will be together.

U.S. surgeon general is calling for alcohol warning labels to note cancer risk. Why they haven’t been updated in 36 years.

Isn’t that due to political reasons?

Or financial considerations? Which is what politics is all about.

This forum is about longevity and health.

The titles of each thread are clearly there to see. Concentrate your attention to those you think are most relevant and we will all be happier.

I agree. And some people seem to derive major psychological benefits from a glass.

But its not physiologically healthy for most, and disastrous for a small percentage as it leads to dependency.

That is the major problem I have with most “alcohol in moderation is good for you” studies. Do they follow what happens to the 11 percent that become problem drinkers? Because drinking in moderation assumes easy control, which is hardly true for that population.

I think this is a good analysis of this issue (reports of “moderation” of alcohol is a net positive):

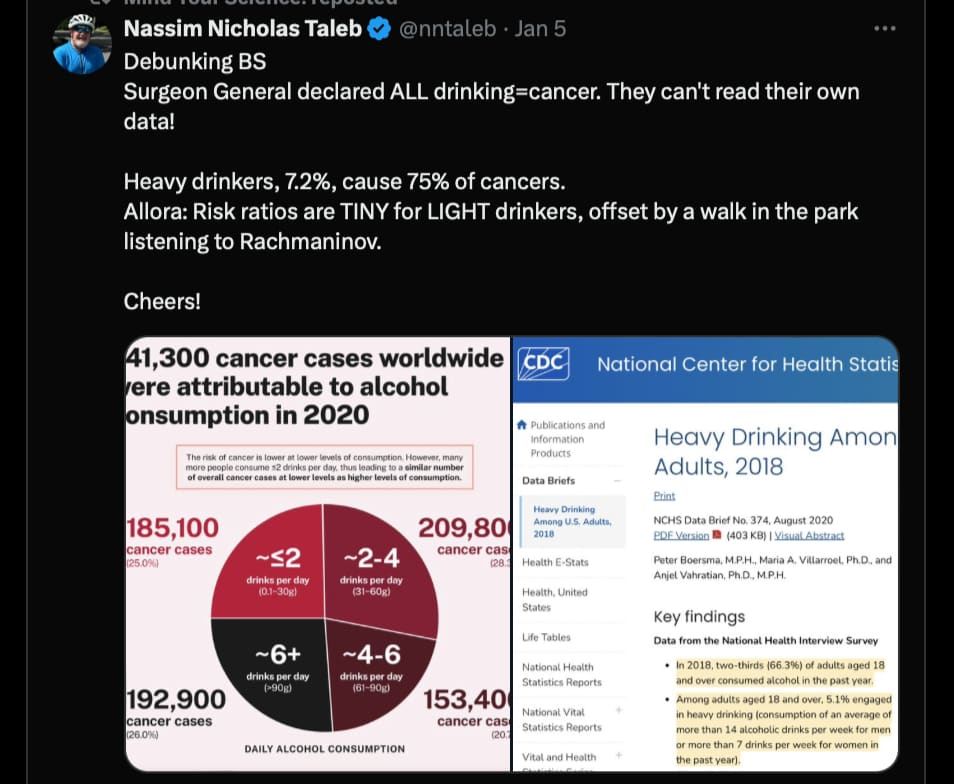

From this X post: x.com

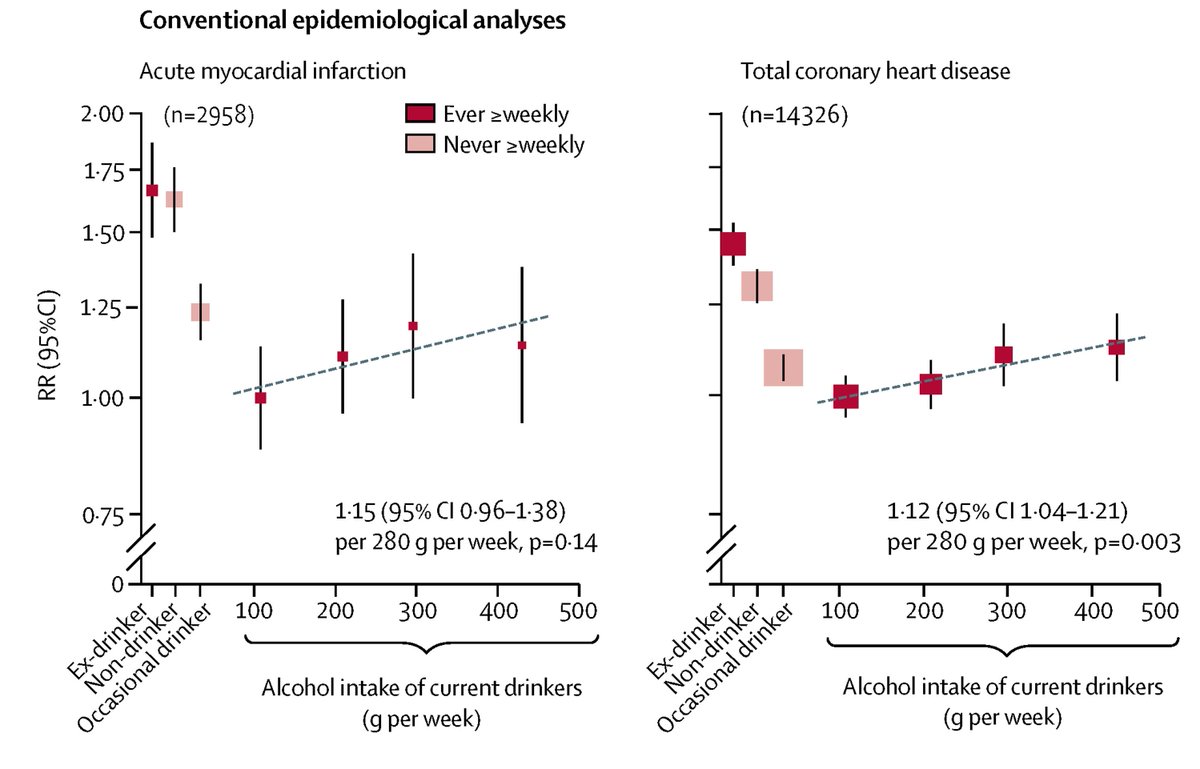

Everyone knows that alcoholism is bad. Drink too much, you’ll fry your brain, or so the wisdom goes. But it’s also common knowledge that a little bit of alcohol is good for you. I mean, just take the conventional epidemiological result:

Clearly people who used to drink and people who never drink do worse than the people who drink a bit. And when people start drinking even more than a bit, they look a little better. Beyond that, they start to look a bit worse, but at no point are they worse than the non-drinkers. Right?

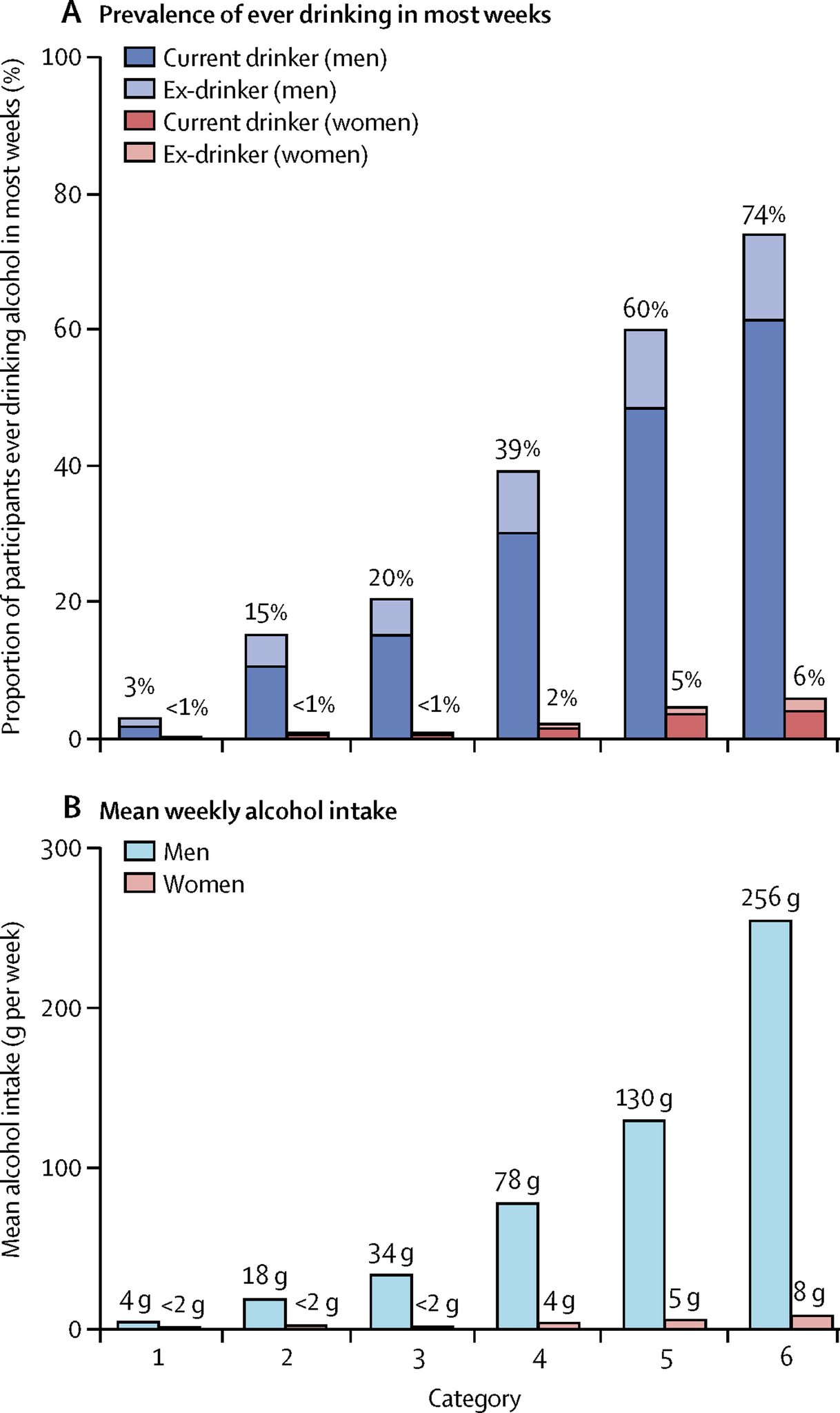

The problem with the conventional analysis is that selection is at play. The people who don’t drink at all and the ex-drinkers are selected into not drinking in weird ways. For example, an ex-drinker might be someone who was a heavy drinker in the past; a never-drinker might be a socially odd person. Who knows! But the potential that they’re not normal is very much there. It would be unethical to run human experiments to figure out what alcohol does, so, how can we know what alcohol does to health? With a clever little method called Mendelian Randomization, or MR. MR is basically an answer to the question What if I used genes as instrumental variables? Using Chinese data and genes that affect alcohol metabolism, that’s exactly what Millwood et al. did! Since the alcohol metabolism genotypes they used should be otherwise independent of risk, everything should be good to go for using these as predictors of alcohol’s effects. But just to be sure: one of the ways we know these genotypes don’t have independent effects is that there were no effects in women, who, for cultural reasons, are pretty close to being non-drinkers. Just take a look at the male-female difference in drinking!

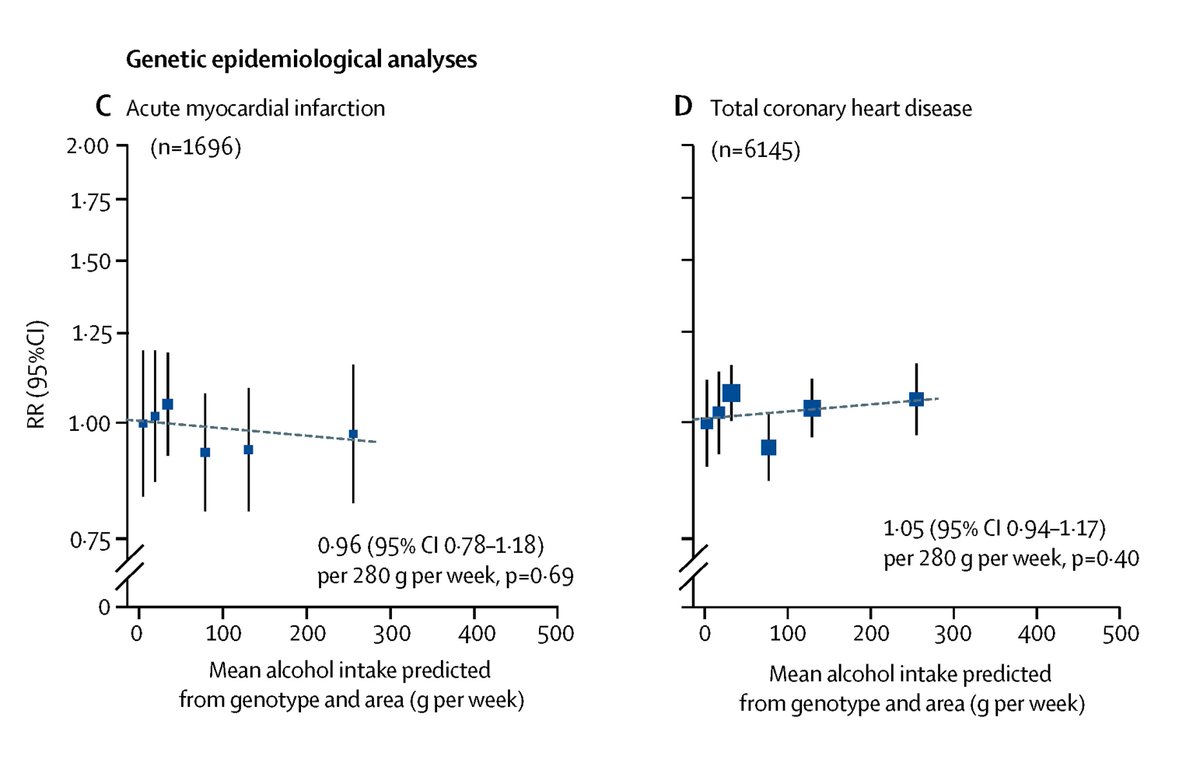

So putting this wonderful genetic predictor to use, we can finally see what alcohol actually does. Well, the effect of the unconfounded difference in alcohol consumption is that, when it comes to heart health, alcohol doesn’t seem to do much, rather than being a bit protective.

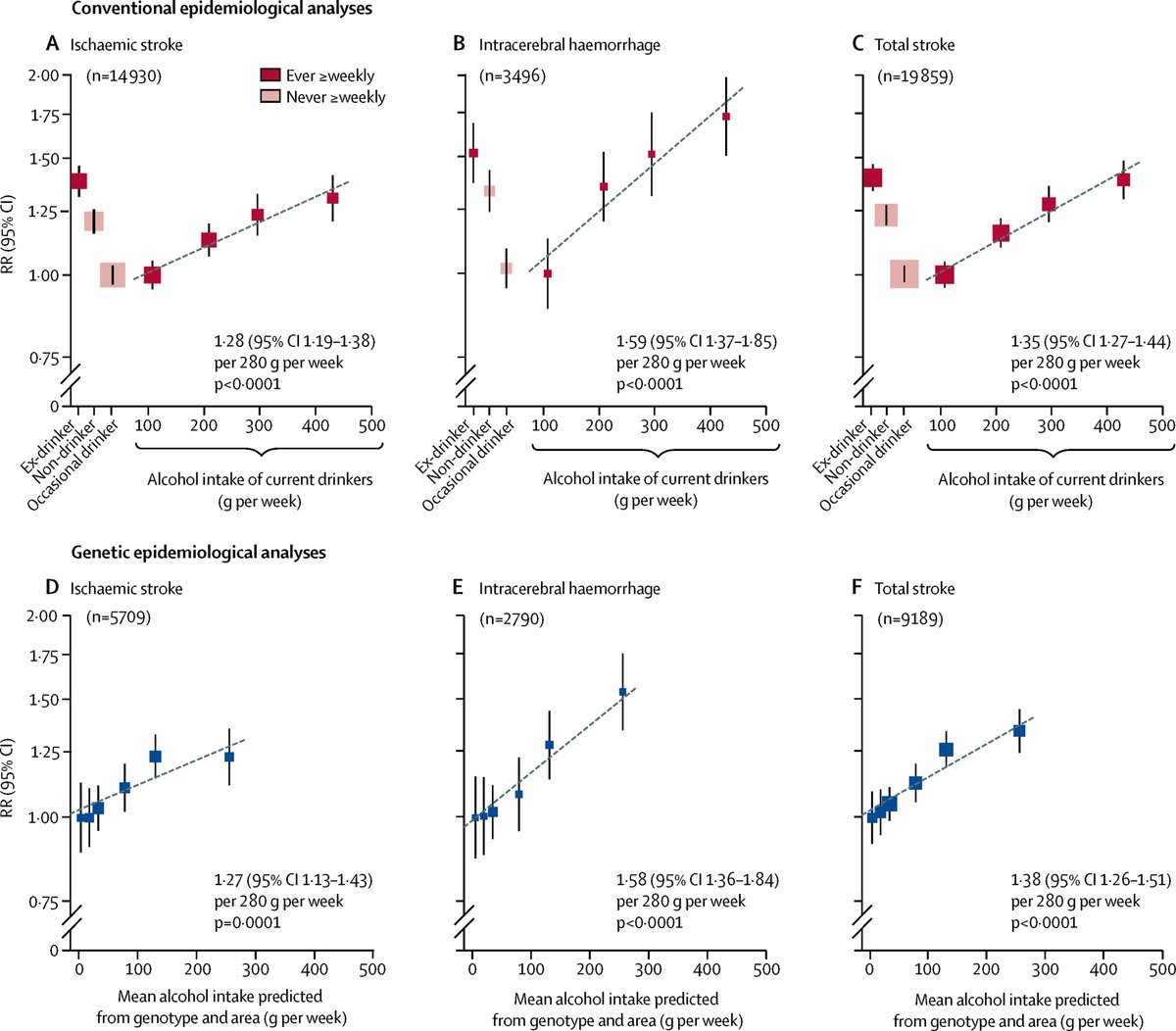

But the heart isn’t everything. There’s certainly more!

Alcohol did increase risk for ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and total strokes. Not only that, but in another study using a similar method, alcohol increased hypertension, blood pressure, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, fasting blood glucose, and triglycerides. But, consistent with these results, in that paper it didn’t seem to have a significant effect on cardiovascular disease or coronary heart disease, and it both increased HDL and decreased LDL. In aggregate, alcohol is likely to be bad for your health at any level, but selection into disuse means the downsides have been hidden in traditional analyses. And even if alcohol doesn’t negatively impact heart health on its own, the fact that it’s not protective and it increases other risks means it’s risky on net.

Sources:

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31772-0/fulltext

Really good work. Thanks.

So this second set does take the adverse effects of immoderation into account? That is a new one for me and I really appreciate that more complete insight.

I think a lot of the harm comes from acetaldehyde.

But there is little indication who will become heavy drinker and who will not.

Starting to drink leads to a meaningful percentage being heavy drinkers, so we should look at the aggregate results for all causes.

That has been my point all along. Everyone who starts drinking is sure they will not have a problem. About 10% actually do. And of those that do, it results in disastrous health span and quality of life outcomes.

It gets worse. A meaningful percentage of problem drinkers develop the problem over many years as they build tolerance. And while women are more likely to seek help, most men do not.

Popular weight loss drug could stifle alcohol abuse

Semaglutide, a mimic of the hormone glucagonlike peptide-1 marketed as Ozempic and Wegovy, slashed alcohol consumption versus a placebo

In the new study in JAMA Psychiatry , 48 people with a drinking problem were randomized to get either 9 weeks of semaglutide or a placebo. Those getting semaglutide consumed about 40% less than the people getting placebo shots when offered their favorite alcoholic beverages. Scientists say trials with more people are now needed.

https://www.science.org/content/article/popular-weight-loss-drug-could-stifle-alcohol-abuse

Finally, @John_Hemming , some good news about alcohol ![]()

Drinking alcohol is bad in many ways; raising a glass can raise your risks of various health problems, such as accidental injuries, liver diseases, high blood pressure, and several types of cancers. But, it’s not all bad—in fact, it’s surprisingly good for your cholesterol levels, according to a study published today in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers at Harvard University led the study, and it included nearly 58,000 adults in Japan who were followed for up to a year using a database of medical records from routine checkups. Researchers found that when people switched from being nondrinkers to drinkers during the study, they saw a drop in their “bad” cholesterol—aka low-density lipoprotein cholesterol or LDL. Meanwhile, their “good” cholesterol—aka high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or HDL—went up when they began imbibing. HDL levels went up so much, that it actually beat out improvements typically seen with medications, the researchers noted.

It’s the residual confounding in studies that show an association of high HDL-c being harmful according to Kastelein iirc.

How the Risks of Drinking Increase in Older Age

Alcohol can present health problems for even light or occasional drinkers.

Drinking is harmful to your health at any age. But as you get older, the risks become greater — even with the same amount of drinks.

Alcohol affects “virtually every organ system in the body,” including the muscles and blood vessels, digestive system, heart and brain, said Sara Jo Nixon, the director of the Center for Addiction Research & Education at the University of Florida. “It particularly impacts older adults, because there’s already some decline or impact in those areas.”

“There’s a whole different set” of health risk factors for older drinkers, said Paul Sacco, a professor of social work at the University of Maryland, Baltimore who studies substance use and aging. People might not realize that the drinks they used to tolerate well are now affecting their brains and bodies differently, he said.

According to Dr. Nixon’s research, older people also show deficits in working memory at lower blood alcohol concentrations than younger drinkers. In another study Dr. Nixon worked on, some older adults in driving simulations showed signs of impairment after less than one drink.

Drinking alcohol can increase the risk of developing chronic conditions like dementia, diabetes, cancer, hypertension and heart disease. But it can also worsen outcomes for the majority of older adults already living with chronic disease, said Aryn Phillips, an assistant professor of health policy and administration at the University of Illinois Chicago who studies alcohol and aging.

Drug interactions also come into play. Mixing alcohol with prescription medicines that older adults commonly take, such as those for treating diabetes or hypertension, can make the medications less effective or cause harmful side effects, like ulcers or an irregular heart beat

Maha ha ha…

The Department of Health and Human Services has pulled back a government report warning of a link between cancer and drinking even small amounts of alcohol, according to the authors of the research.

Their report, the Alcohol Intake and Health Study, warned that even one drink a day raises the risk of liver cirrhosis, oral and esophageal cancer, and injuries. The scientists who wrote it were told that the final version would not be submitted to Congress, as had been planned.

The report is one of two assessments that were to be used to shape the new U.S. Dietary Guidelines’ recommendations on alcohol consumption. Its early findings were reported by The New York Times in January; a full draft remained on the H.H.S. website as of Friday afternoon.

A competing report, written by a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine panel, came to a conclusion long supported by the industry: that moderate drinking is healthier than not drinking. Some panelists came under criticism for financial ties to alcohol makers.

and here is the Full Draft of the scientific report that I suspect will disappear from the HHS website very soon and be replaced by the industry approved version.

2025-draft-public-comment-alcohol-intake-health-study.pdf (1.9 MB)