Open Access Paper:

AI Summary and Critique:

Here is a detailed summary, novelty assessment, and critique of the paper Inhibition of spontaneous mutagenesis by vanillin and cinnamaldehyde in Escherichia coli: Dependence on recombinational repair by Shaughnessy et al. (2006) (PMCID: PMC2099251). I’ve tailored it toward your advanced interest in mechanistic and biomarker-type analysis.

Summary

Background

- The authors study two dietary flavouring compounds, vanillin (VAN) and cinnamaldehyde (CIN). Prior work had shown these compounds reduce induced and spontaneous mutation frequencies in bacterial test-systems. (PubMed)

- The hypothesis: these compounds may reduce spontaneous mutagenesis via modulation of DNA repair pathways — in particular, the authors wondered whether the recombinational repair (RecA) pathway, the SOS response, mismatch repair (MMR), or nucleotide excision repair (NER) might be required for the antimutagenic effect.

Methods

- Bacterial model: various E. coli strains derived from wild-type strain NR9102, each with defined defects in DNA repair: e.g., NER-deficient (uvrB), recombination-deficient (recA56), SOS-deficient but recombination-proficient (recA430), mismatch repair-deficient (mutL), etc. (PubMed)

- The compounds VAN and CIN were applied at non-toxic doses to the various strains, and the spontaneous mutation frequencies (e.g., at lacI or other marker) and survival were measured. The key comparisons were: effect on wild-type; effect on each repair-deficient background.

- They interpret whether the antimutagenic effect (i.e., reduced spontaneous mutant frequency) persists or fails in each background, to infer which repair pathways are required.

Key Results

- In wild-type strain NR9102: Both VAN and CIN significantly reduced spontaneous mutant frequency (while not being overtly toxic at the selected doses). (PubMed)

- In the NER-deficient uvrB strain: Both compounds still showed reduction in mutant frequency — thus NER is not required for their antimutagenic effect.

- In the SOS-deficient but recombination-proficient strain (recA430): They also observed reduction in mutants, indicating the SOS induction per se is not necessary.

- In the recombination-deficient (recA56) strain: Both VAN and CIN failed to reduce spontaneous mutants — actually in some cases the mutant frequency increased — indicating that recombinational repair (RecA) is required for the antimutagenic effect.

- In the mismatch repair-deficient mutL strain: Only CIN showed antimutagenic effect; VAN did not reliably reduce mutants in that background. This suggests the MMR pathway may modulate the effect in a compound-specific way.

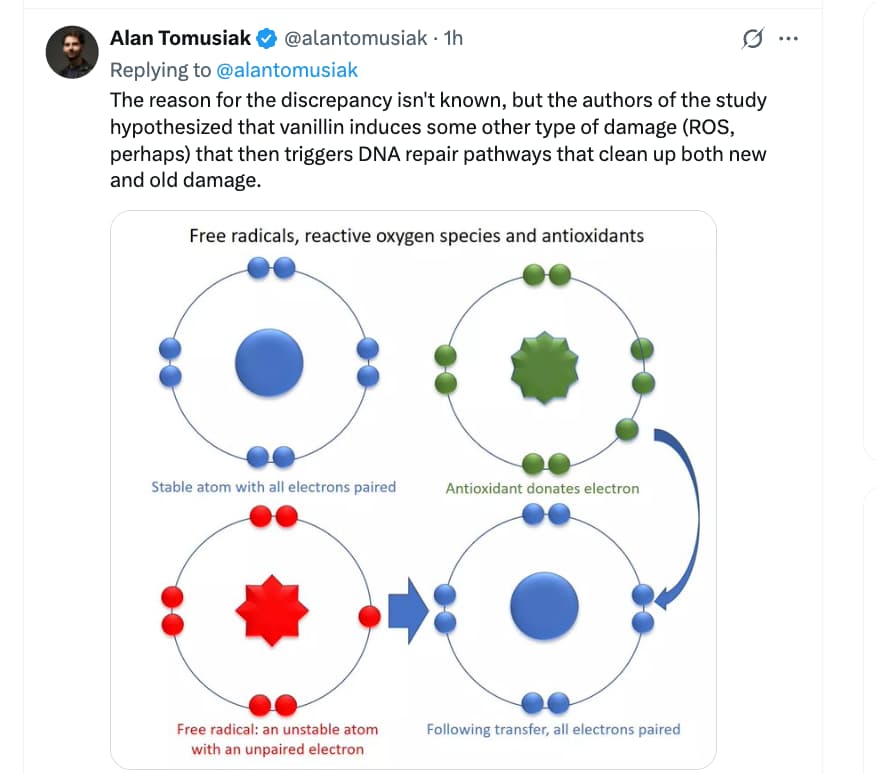

- Interpretation: The authors propose that VAN/CIN may induce a low level of DNA damage (or DNA lesions) that specifically stimulates recombinational repair, and that that repair then removes not only the VAN/CIN-induced damage but also other spontaneous damage, thereby reducing the overall spontaneous mutant frequency.

Conclusions

- The antimutagenic effect of vanillin and cinnamaldehyde against spontaneous mutation in E. coli requires the RecA recombinational repair pathway, but is independent of NER and of the classical SOS induction.

- They propose a “counterintuitive” mechanism: the compounds themselves cause a form of low-level DNA damage (or a signal) that triggers recombinational repair, thereby decreasing the load of spontaneous mutational events.

- Implication: dietary antimutagens may act not simply by scavenging mutagens or preventing damage but by up-regulating error-free repair pathways.

Novelty

This paper has several points of novelty (especially as of 2006) which are worth highlighting:

- Focus on spontaneous mutagenesis rather than induced (exogenous) mutagenesis. Many antimutagen studies focus on reducing mutation from known mutagens; here they focus on the baseline spontaneous mutation frequency. That is interesting for understanding background mutagenesis and potential “chemopreventive” modulation of repair.

- Use of multiple defined E. coli repair-deficient strains to dissect the required repair pathways for the antimutagenic effect. The fact that reduction fails in a recombination-deficient strain but not in NER or SOS-deficient indicates a quite specific mechanistic inference.

- Hypothesis of damage-induced repair activation: The proposition that an “antimutagen” works by causing mild damage that upregulates recombinational repair is conceptually provocative. It flips the common idea (antimutagen = prevents damage) to “antimutagen = triggers repair of spontaneous damage”.

- Implications for dietary agents and endogenous repair modulation: The suggestion that diet-derived small molecules might enhance error-free repair pathways and thereby reduce mutagenesis is an interesting translational angle (though in bacteria).

- The morphological details (mutation spectrum, repair backgrounds) strengthen the mechanistic argument: showing that the effect is RecA-dependent is fairly precise.

Therefore, for mechanistic toxicology/genotoxicity, this paper stands out as a clear attempt to link dietary antimutagenic compounds with specific DNA repair pathways in a spontaneous-mutation context.

Critique

From your vantage of rigorous biomarker/repair/optimization interest, here are the strengths and limitations of the paper (and what to keep in mind if translating to higher organisms or longevity/repair contexts).

Strengths

- Well-controlled genetic backgrounds: The use of E. coli strains with defined defects allows a relatively unambiguous inference about repair pathway dependence (e.g., RecA/recA56).

- Clear experimental design: The dose-selection (non-toxic), measurement of both survival and mutation frequency, and comparing across multiple strains is robust.

- Mechanistic insight: The paper goes beyond saying “it works” to ask how it works — which is aligned with your interest in underlying pathways (e.g., recombinational repair) rather than just phenomenology.

- Relevant to spontaneous mutation: Spontaneous mutation is important for baseline genome stability; targeting that is relevant to longevity/repair modelling.

Weaknesses / Limitations

- Model system is prokaryotic (E. coli): The translation to eukaryotes (let alone humans) is highly uncertain. Bacterial repair systems differ (though RecA has analogues) and spontaneous mutation loads, repair contexts, chromatin, etc differ enormously. So caution in generalizing to human biomarker/therapy context.

- Assumption of low-level damage induction: The proposed mechanism—that VAN/CIN cause mild DNA damage to trigger recombinational repair—is not directly demonstrated in this paper (in the bacterial system) by, say, measurement of DNA breaks or repair kinetics. So the model remains speculative.

- Lack of dose-response and detailed kinetics of repair induction: While they show reduction of mutants, they don’t deeply explore the time-course or repair induction signalling (e.g., monitoring RecA induction, recombination intermediates, etc).

- Potential off-target or indirect effects: The compounds may have pleiotropic effects (e.g., antioxidant activity, modulation of growth rate, reactive metabolites) which might influence mutation frequency in ways not strictly tied to repair. The authors don’t fully rule out all alternate mechanistic routes (for example, growth rate slowing affecting mutagenesis, or metabolic perturbation).

- Spectrum of mutations: Although earlier work by the group (Setzer et al.) looked at mutation spectra (GC vs AT) in Salmonella, this paper does not deeply dig into mutation spectrum shifts in these E. coli strains, which could give more insight into mechanism (e.g., what kinds of lesions are being repaired).

- Potential for bias in “antimutagenic” interpretation: Because the model proposes that inducing damage leads to less spontaneous mutation overall (via repair), there is a risk of mis-interpreting a stress-response as beneficial; this might not hold in long-term exposure or in eukaryotes where repair induction might lead to other adverse consequences (e.g., error-prone repair, cell cycle perturbation).

- Lack of longevity or higher‐order endpoints: For your interest in longevity/repair biomarkers, the paper doesn’t address whether the antimutagenic effect translates into lower mutation accumulation, genome stability over time, or functional outcomes.

Specific Points to Consider

- The requirement for RecA (recombination repair) is strong evidence, but what about the role of other recombinases, Holliday-junction resolvases, or homologous recombination vs single-strand annealing? The paper is silent.

- The independence from the SOS response is interesting (i.e., recA430 strain), but the paper doesn’t measure actual SOS induction or gene expression changes in these strains, so the inference is indirect.

- Growth and survival effects: The authors note that at the doses used the compounds are “non-toxic” (but they still affect survival at higher doses). Sub-toxic growth inhibition or metabolic stress could itself reduce replication/ mutation sampling and thus lower mutation frequencies. The authors believe they control for this, but residual metabolic perturbation remains a confounder.

- For spontaneous mutation, there are multiple possible lesion types (oxidative damage, replication errors, endogenous adducts). The paper doesn’t identify which substrate(s) are being repaired via the recombination pathway under these conditions. That limits mechanistic specificity.

- Because they observe that in the recA56 strain the compounds increase mutation frequency (rather than merely lose beneficial effect), one wonders whether VAN/CIN are acting as mild genotoxins in that repair-deficient context — i.e., they cause damage that cannot be repaired → higher mutants. This raises a caution: in repair-deficient contexts the compounds might be harmful.

Relevance to your interests (biomarkers, longevity, repair)

- The proposition that small dietary compounds might stimulate error-free repair pathways (here recombination) is of interest in the longevity/repair optimisation domain. However, the bacterial model and indirect mechanism mean application to humans is speculative.

- If one were designing a biomarker study in human cells (or a human trial) to test the effect of vanillin/cinnamaldehyde (or analogues) on spontaneous mutation/repair, one should include direct measures of DNA damage induction (e.g., γH2AX, comet assay), repair pathway activation (e.g., RAD51 foci for recombination), mutation burden over time (e.g., HPRT locus, next-gen sequencing), and evaluate whether induction of repair is beneficial rather than harmful (i.e., avoid adverse repair pathway activation).

- For modelling mutation accumulation in aging, the concept of up-regulating recombinational repair is appealing, but one must consider trade-offs (e.g., recombination in somatic cells can lead to chromosomal rearrangements, loss of heterozygosity, etc). Thus the paper gives a mechanistic hypothesis but no data on such trade-offs.

Final Thoughts

Overall, the paper by Shaughnessy et al. is solid within its domain (bacterial genetic toxicology) and offers an interesting mechanistic hypothesis linking dietary compounds to repair pathway modulation. Its key novelty lies in the demonstration that the antimutagenic effect of vanillin and cinnamaldehyde against spontaneous mutation in E. coli requires recombinational repair (RecA) but not NER or SOS induction.

However, for your interest in translation to human biology, ageing, repair biomarkers and longevity, one must view the findings as hypothesis-generating rather than definitive. The leap from bacteria → human, from short‐term reduction of mutation frequency → long-term genome stability or functional benefit, remains large and unproven.