To take this in yet another direction, the concept of an aging clock is appealing to many, including myself. However, despite my efforts, the work on this to date has been less than impressive, and in some ways, it seems lacking in scientific rigor and logic. Given the high caliber of this group (the best, in my opinion), I’m sure some of you recall Wittgenstein’s caution against searching for a single criterion that unites all uses of a term (or construct). He argued persuasively that many terms do not share one common feature but instead are linked by numerous overlapping threads, forming what he called a “family resemblance.” A metaphor often used to illustrate this idea is that of a long, strong rope, through which no single strand runs end-to-end.

The notion of a true aging clock presupposes or implies some sort of master orchestration of all structures and functions—something that “directs” or otherwise leads to the gradual decline in their integrity.

I still appreciate the elegance of this model, but it has yet to be substantiated, even weakly, and support for the current contenders, such as methylation, seems to be waning.

There is an alternative to the “clock” model. Based on current evidence, it seems equally plausible that structures and functions decline both independently and interactively, driven by a variety of unrelated causes, some of which are random. For example, declining kidney function caused by the acquisition of a rogue virus while traveling might trigger a cascade of aging events, eventually leading to death. The inheritance of a BRCA gene can result in numerous aging-related events. Background radiation levels differ between geographic locations. One person’s chronic stress may lead to hardened and blocked arteries, while another individual with the same lipid profile, who has mastered stress management, might not experience this outcome. We can all think of such examples. Is there a master clock behind these events? Not necessarily. Our genes, our environment—including epigenetic factors—what we learn, and what we believe, all play a role, and none of these are orchestrated by or answer to a master clock. Aging may simply represent a gradual decline in structural and functional integrity, driven by a multiplicity of causes, some of which are unpredictable or unknowable.

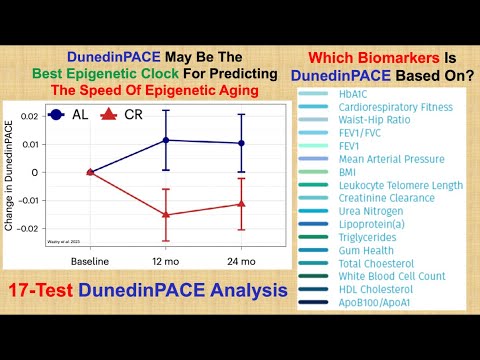

Viewing aging as a complex, non-clock-driven process does not dismiss the utility of so-called “aging clocks,” which often consist of lists of scientifically validated health metrics. However, these lists are not clocks in any meaningful sense. What they do offer is a collection of factors to monitor and manage. Through empirical research, these lists can be refined, made more precise, and perhaps even simplified, with a focus on atomic (as opposed to derived) metrics. This type of research could eventually lead to a more parsimonious index, benefiting the management of age-related challenges. I believe this is a goal we all share.

Of course, I’m open to alternative perspectives or further development of this idea.