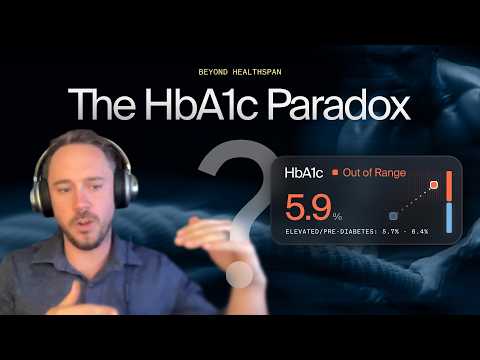

New article that talks about something that has puzzled me over the last 2-3 years: A1C in the pre-diabetic range, despite low fasting glucose and more importantly, low fasting insulin (I tested for both). One year ago, I was at 5.7, 3 and earlier this year at 5.8 (officially pre-diabetic).

One of the most overlooked factors influencing HbA1c is the biology of red blood cells themselves. Hemoglobin A1c reflects a process called glycation, where glucose binds to hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. This glycation is non-enzymatic and irreversible, meaning that once glucose attaches to hemoglobin, it remains there for the life of the red blood cell. Because the average red blood cell lives around 120 days, HbA1c is interpreted as a reflection of average glucose exposure over the previous two to three months.

But that 120-day assumption isn’t universal. The lifespan of red blood cells can vary depending on several physiological factors, and when they circulate for longer than average, they have more time to accumulate glycation. Think of each red blood cell as a sponge moving through sugar water: the longer it stays in that environment, the more sugar it picks up. Even if the sugar concentration in the water doesn’t change, a sponge that’s been there longer will end up holding more. Similarly, red blood cells exposed to normal glucose levels for an extended period can accumulate more glycated hemoglobin, causing the HbA1c level to appear elevated, even when metabolic health is excellent.

This becomes particularly relevant in the context of endurance-trained athletes. Chronic aerobic training leads to subtle yet significant adaptations in red blood cell physiology. For one, as the body becomes more efficient at delivering oxygen, thanks to increased capillary density, mitochondrial function, and improved oxygen extraction, there is less mechanical and oxidative stress on red blood cells. This allows them to circulate longer before being broken down and replaced. At the same time, consistent training tends to reduce systemic inflammation and upregulate antioxidant defenses, both of which help preserve red blood cell integrity and delay cell turnover. Over time, these adaptations can lead to a population of red blood cells that survives slightly longer than the standard 120 days