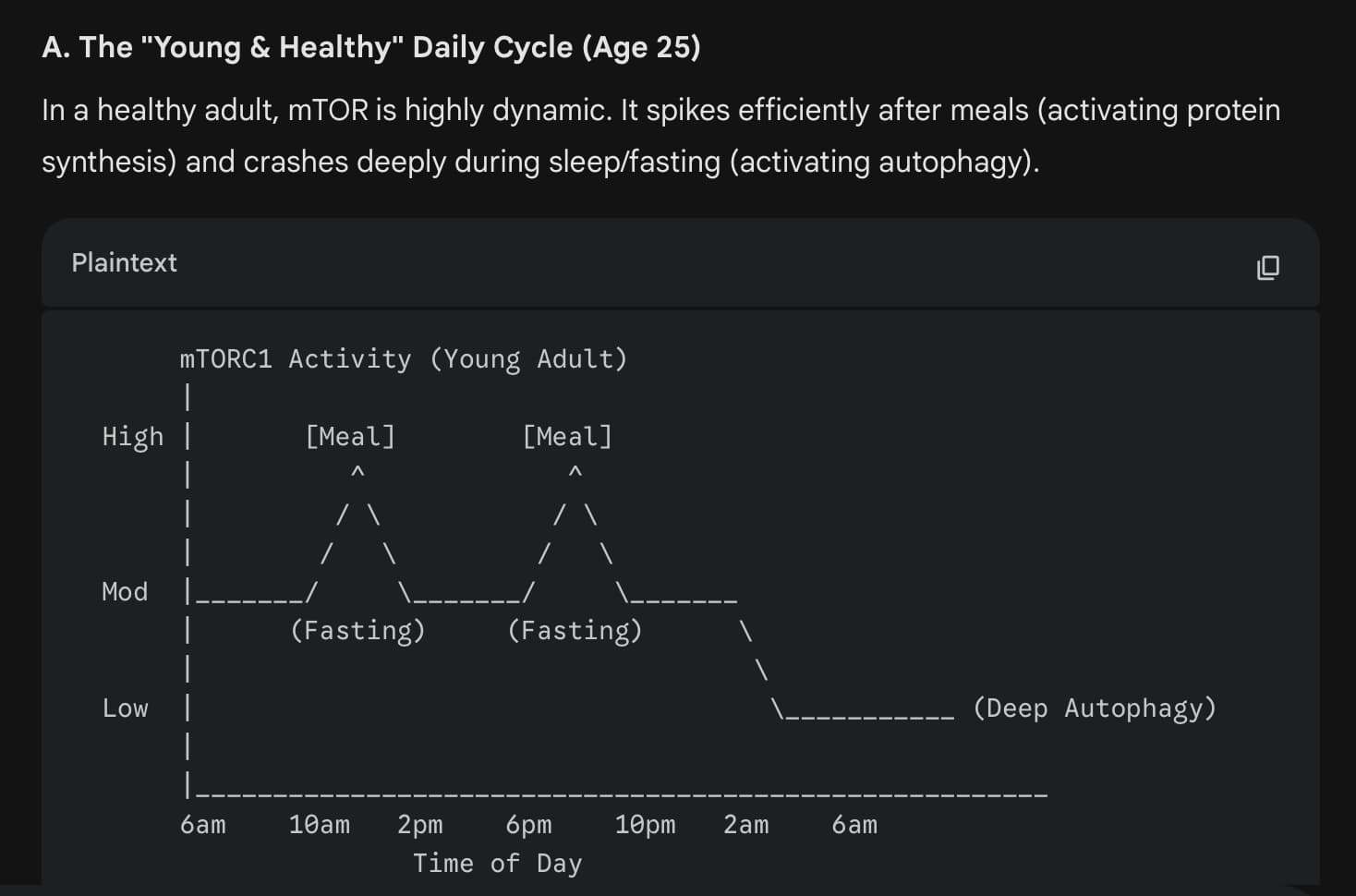

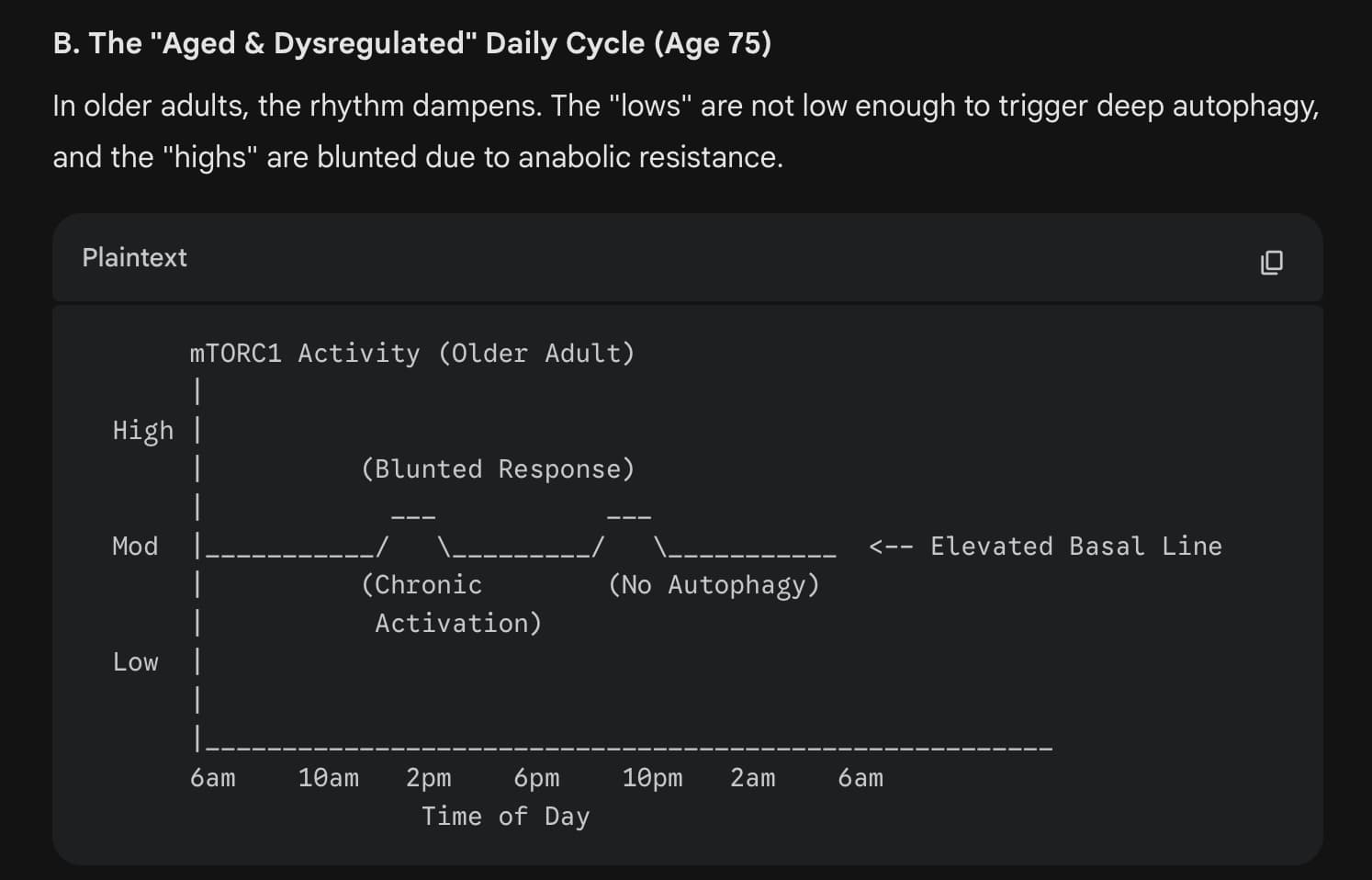

In this comprehensive narrative review, researchers from Newcastle University dissect the “selective vulnerability” of aging skeletal muscle, challenging the simplistic view that muscles just “shrink” with age. Instead, they present a precise, hierarchical decay: Type II (fast-twitch) glycolytic fibers—the engines of power and speed—are decimated by aging, while Type I (slow-twitch) oxidative fibers remain relatively preserved. The authors identify a “denervation-reinnervation” cycle as a primary driver, where motor neurons detach from fast fibers, forcing them to atrophy or be “rescued” by slow motor neurons, creating “hybrid fibers” (co-expressing Type I/II myosin). This structural chaos is underpinned by a paradox: older muscles exhibit hyperactive basal mTOR signaling yet fail to respond to anabolic stimuli (“anabolic resistance”), effectively locking the muscle in a state of decay despite nutrient availability.

Source:

- Open Access Paper: Ageing of human myofibres in the Vastus Lateralis muscle: A narrative review

- Context: Institution: Newcastle University, UK Journal: Ageing Research Reviews

- Impact Evaluation: The impact score of this journal is 12.4-13.1 (JIF 2024/2025), evaluated against a typical high-end range of 0–60+ for top general science. Therefore, this is an Elite/High impact journal, ranking Q1 in Geriatrics & Gerontology.

Part 2: The Biohacker Analysis

Study Design Specifications

-

Type: Narrative Review (Synthesis of historical histology, recent multi-omics, and imaging data).

-

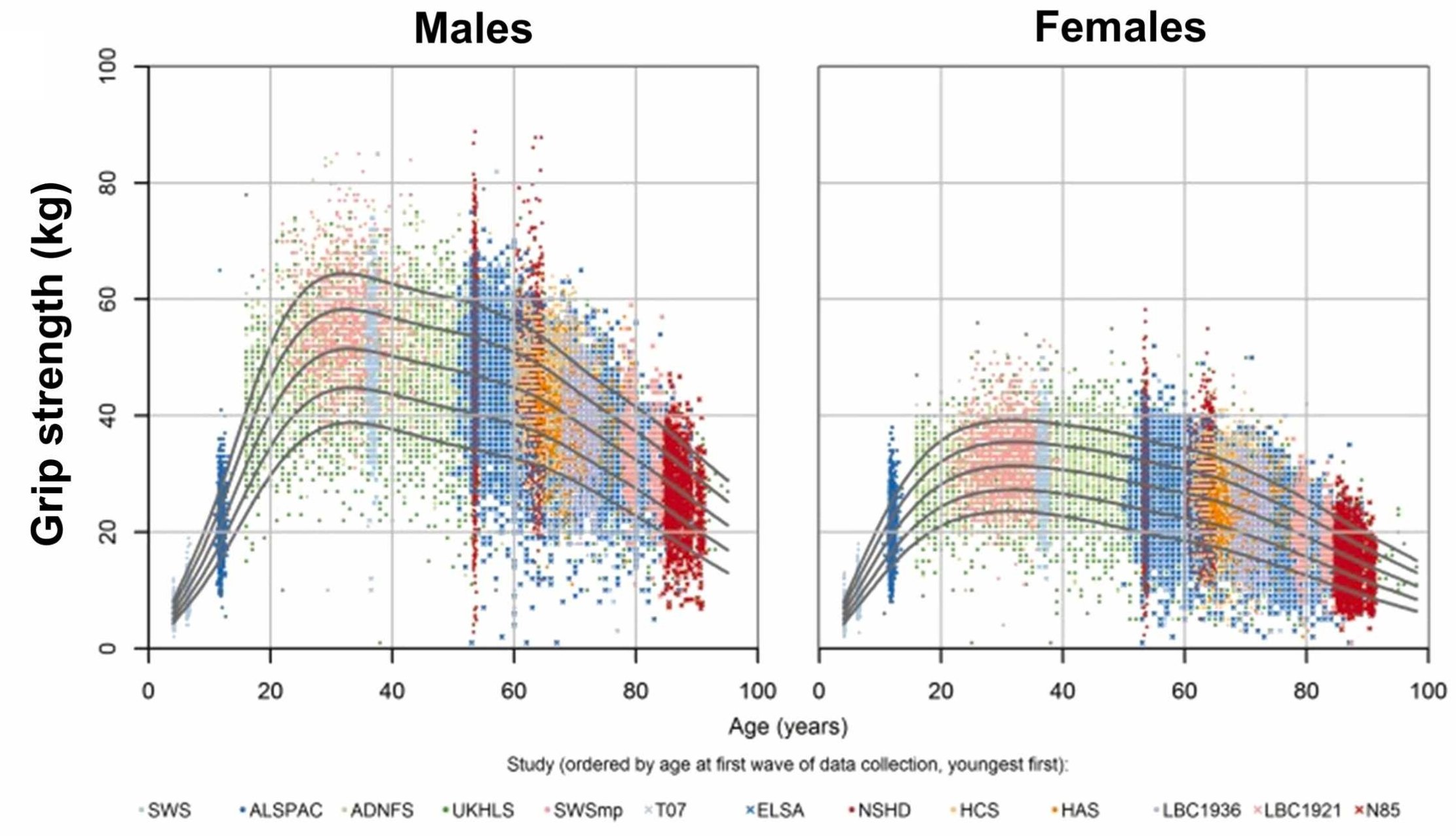

Subjects: Human cohorts (aggregated data). Focuses on Vastus Lateralis (VL) biopsies from healthy young (18-49y) vs. older (>60y) adults.

-

Mechanistic Deep Dive:

- The mTOR Paradox: The review highlights that while mTORC1 is essential for hypertrophy, it is constitutively hyperactive in aging muscle (basal elevation). This chronic “on” switch may drive insensitivity to actual anabolic signals (exercise/protein), creating a feedback loop of atrophy—a phenomenon termed “anabolic resistance.”

- Neuro-Aging (The Denervation Cycle): The degradation of the Neuromuscular Junction (NMJ) is not a byproduct but a driver of sarcopenia. Fast motor units die off; surviving slow motor units sprout axons to “adopt” the orphaned fast fibers. This converts them to slow or “hybrid” fibers (Type I/II co-expression), preserving mass but sacrificing explosive power.

- Mitochondrial Fragmentation: Type II fibers, which have fewer mitochondria to begin with, suffer disproportionate mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS accumulation compared to the dense, reticular networks in Type I fibers.

-

Novelty:

- Identifies “Hybrid Fibers” (co-expressing MyHC isoforms) not just as anomalies, but as a defining biomarker of the aging muscle’s desperate attempt to re-innervate.

- Challenges the efficacy of antioxidant supplementation, noting that low-level ROS is necessary for adaptation, and exogenous antioxidants may exacerbate atrophy.

-

Critical Limitations:

- Survivor Bias: Most data relies on cross-sectional biopsies (healthy survivors) rather than longitudinal tracking, potentially underestimating fiber loss in frail populations.

- The “Female Gap”: The authors explicitly flag a paucity of data on female muscle aging, despite clear sexual dimorphism in fiber distribution.

- Methodological Noise: Aggregates studies using different typing methods (ATPase vs. Immunofluorescence), creating noise in “hybrid fiber” quantification.