I found plenty of discussion of people seeing their A1c rise and fall due to various causes (diet changes, rapa intake, metformin use, etc. etc.). Obviously I can google enough to know the definitions of T2D, prediabetes, and normal. But do we have any idea what an ideal A1c is for longevity? I saw something in my search suggesting that below 3.5 has negative effects, but it wasn’t detailed or a great source. I figure people here may have researched this already. Thanks for any input.

Here’s a big discussion on this question

Looks like the answer is 5-5.3 HbA1c. I’m aiming at 5.0 but I’ll take 5.3.

A complexity here is that heavy drinkers reduce their HbA1c. I am an intermittent binge drinker and although I have not tried to analyse it in major detail I think when I had an HbA1c of 4.18% that was in part because I was drinking a lot.

Hence I can see why the figure around 5% is a good target rather than lower although I think the acetate from drinking is potentially useful.

I think U curves based on all cause mortality age valuable datapoints, but are only associations / correlation based stories.

In this case there could be a lot of co-founders for why mortality in the overall population goes up as the lower HbA1c levels - John mentioned one where heavy alcohol drinkers could screw the demographics data. Another one could perhaps be that some cancers steal the glucose from the person and hence is lowers blood glucose and cancer highly correlates with.

On the other hand we know that there are mechanistic reasons for why glucose interacts in a bad way with longevity pathways (insulin up, glycation, cancer growth up, etc, etc)

We also know that there is a lot of longevity data on medicines and protocols that minimize glucose - from CR, to folistatin gen therapy, to all the ITP results on acarbose and Cana/SGLTi, etc.

So I’d like to see more data on why why 5 or 5.3 would be better than 4.7 or 4.8 in my personal situation

Having said that, my current target is more to minimize my glucose spikes and less to further work on average glucose.

Of course it’s also important to take into the indices and the context. Some one fasting several times over the last 3 months and eating more toward keto may have a lower optimal level to target than someone who eats a healthy meditation diet.

There was a study that stated an HBA1C below 4.0 was detrimental to health. So, I would say that 4.0-5.3 is a good range, but 4.7-5.3 is best. I’m sitting at 5.7, but am trying to bring it down to that range which I think should be possible by my next blood test.

Thanks. I tried to look into it. Is this the paper?

If so please, please note that (a) the paper is just association based and (b) the authors of the paper seem to be saying that low levels can be a suggestion that there is a disease process going on.

Ie it can be a good warning sign if it starts dropping. But that is not the same as as low levels are bad in cases where such diseases processes are not going on.

Ie they seem to be saying that certain disease > low HbA1c and not just HbA1c > disease or mortality.

Think we have to be very careful when drawing causal inferences for association or correlation data.

The abstract says:

Participants with a low HbA1c (<4.0%) had the highest levels of mean red blood cell volume, ferritin, and liver enzymes and the lowest levels of mean total cholesterol and diastolic blood pressure compared with their counterparts with HbA1c levels between 4.0% and 6.4%.

So it might for instance be that people who have severe liver disease or liver cancer (together a quite large part of the population) end up with lower glucose (because the liver is the master controller of glucose).

If so it would be

Liver disease > mortality

and

Liver disease > low HbA1c

And while that means the

low HbA1c correlates with the mortality

HbA1c is not the causal driver which in this example is the liver disease

I read a little bit more in the paper and what is was saying seem to be the perspective of the authors too?

Very low HbA1c values among persons without diabetes may reflect underlying biological processes.

Certain health conditions that decrease erythrocyte life span (eg, iron-deficiency anemia) are known to alter HbA1c values and make them unreliable

That means that such diseases are not only probably part of some of the mortality but they H1c is not even measuring their actual average glucose levels, but giving a read out that is lower than their actual glucose exposure…

Clearly that is not relevant for most of us who don’t have any artificial lowering of how long our red blood cells live?

little is known about other biological factors that result in low HbA1c values among individuals without diabetes. Low HbA1c may not reflect metabolic control among individuals without diabetes but may be reflecting other biological factors, such as red blood cell markers, inflammation, or decreased liver function

Hence it is inflammation, liver disease etc that drives low H1c and mortality

H1c hence ends up correlated with mortality but not causally

Please let me know i was looking at the wrong paper or if I am missing something

Your liver targets a level of about 5.0 or higher for HBA1C. If you try to lower it significantly below that, it is a sign of disease as your liver tries but cannot increase glucose release into the blood. Here’s another study that recommended 5.0.

IMHO, 4.6-4.9 is fine as well. Things start to get a bit iffy when you drop into the 4.0-4.5 range and it’s a warning sign when it drops to below 4.0.

Thanks. I’ll take a look.

I’ll try to look into this a more after I get back from travel. But don’t think that cut off is correct. Peter Attia’s calculation is that 4.6% represents estimated average glucose levels of 85 mg/dL. That does not look like a level that is too low for the liver in a person who is optimized from a metabolic perspective and easily can utilize fat and not just glucose as energy.

From below you can also see that Peter does not seem to feel that HbA1c is 4.6% is negative.

Glucose control lives on a spectrum, but it conventionally gets lumped into three distinct categories: normal glucose tolerance, prediabetes, and diabetes. For example, whether your HbA1c is 4.6% or 5.6%, both are considered “normal” because they both fall under the diagnostic threshold of 5.7%. Once it hits 5.7%, so long as it does not exceed 6.4%, now you’ve got impaired glucose tolerance, also referred to as prediabetes. Once you’ve eclipsed the latter, whether your HbA1c is 6.5% or 12.5% (or even higher), you’re categorized as having type 2 diabetes. In most cases of type 2 diabetes, an individual traverses from one bucket to the next as their HbA1c slowly climbs from normal to impaired to outright diabetic. This doesn’t happen overnight, but too often it’s only confronted when the diabetes or prediabetes threshold is reached at a snapshot in time. Progressing from an HbA1c of 4.6% to 5.6% represents estimated average glucose levels climbing from 85 to 114 mg/dL.

This is where the CGM is more useful than HbA1c. Whar we want are spikes postprandially under 8/140. Then a drop back to 5 or slighrly less.

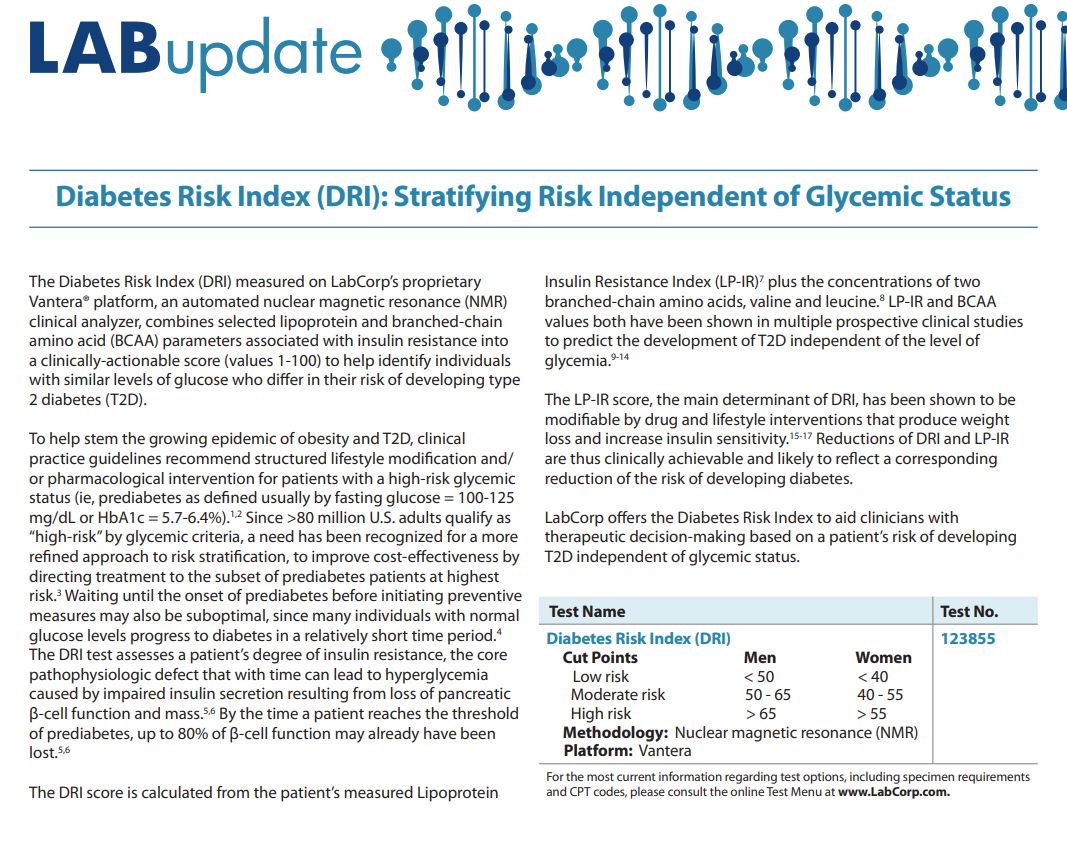

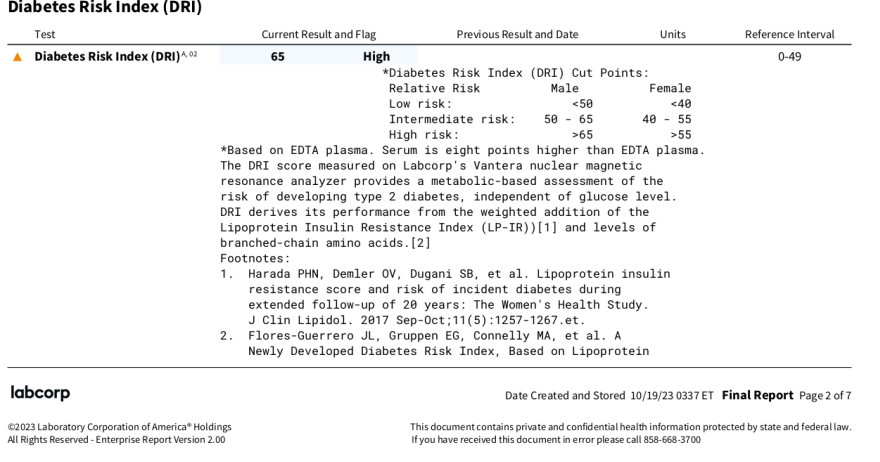

Diabetes Risk Index (DRI)

LabCorp has this test:

https://www.labcorp.com/assets/17270

My result came back with a value of 65, on the cut point between moderate and high risk. This, concurrent with an A1C of 5.4, and fasting glucose in the high 80s, which in isolation wouldn’t seem to imply much diabetes risk.

From the LabCorp writeup:

The LP-IR score, the main determinant of DRI, has been shown to be

modifiable by drug and lifestyle interventions that produce weight

loss and increase insulin sensitivity.15-17 Reductions of DRI and LP-IR

are thus clinically achievable and likely to reflect a corresponding

reduction of the risk of developing diabetes

Briefly looked at the footnoted studies, and it seems I might consider losing weight, chugging olive oil, and going vegetarian. Need to get those polyphenols up!

One might consider doing this test to confirm/disconfirm what they think they already know from A1c

And here he gives his view on that lower average glucose is better and puts that in context of success with a patient who came down to 84 mg/dL and hence at or below a predicted 4.6% HbA1c:

To recap my position and interpretation of the data available (more of which you can find in the AMA 24 show notes), lower is better than higher when it comes to average glucose, glucose variability, and glucose peaks, even in nondiabetics. In other words, there’s a lot of evidence suggesting that people with glucose in the normal range can benefit from lowering their numbers.

Let me give you an anecdote, among several I could share, to demonstrate why I find CGM useful in nondiabetics. I have*** a patient who came to me with normal glucose tolerance by standard metrics. He began CGM and after about two weeks it revealed an average glucose of 104 mg/dL over that time***. The standard deviation in his glucose readings, which is a metric of glucose variability, was 17 mg/dL. He averaged more than five events per week in which his glucose levels exceeded 140 mg/dL. All three of these metrics are considered normal by conventional standards, but does that mean there’s no room for improvement? I like to see my patients with a mean glucose below 100 mg/dL, a glucose variability below 15 mg/dL, and, as noted above, no excursions of glucose above 140 mg/dL. After about a four-week intervention that included exercise changes and nutritional modifications his average glucose fell to 84 mg/dL, his glucose variability to 13 mg/dL, and he had zero events exceeding 140 mg/dL. If he can maintain this way of living in the long-run, it’s likely to translate into an improvement in healthspan and reduce his risk of glucose impairment.

Honestly, I think the sweet spot is 4.6-5.3. I have no idea where I fit in now that I increased my Metformin to 500 mg daily. Hopefully, I’ll be in that sweet spot. I had been thinking about adding empagliflozin, but I am concerned it may drop me into the low 4.0s which I am concerned about. Is there a bottom limit that the SGLT2is won’t drop you below?

I think they kind of hit the spikes more than the average and higher levels more than lower levels. Perhaps check the thread on Cana / SGLT2i.

Perhaps wear a CGM when you begin and then if you were to fall too low you can

- short term/intra day make sure to increase carb intake and then

- near term / between days lower the dose (eg cut a half pill, or given what people said on the other thread about the half life start doing eod dosing)

It’s important to keep in mind that achieving a lower A1c is not necessarily without a cost. And therefore you need to weigh the benefit and cost and see if the overall mortality risk is reduced.

For example, if you achieve a lower A1c by eating less carbs and eating more fat, while you reduce the risk of glycation, you may increase other risks from more fat, such as higher non-HDL lipoproteins, which increases ASCVD risk. Therefore, you’ve traded glycation for a different risk. Are you better off? Maybe, maybe not.

Studies show that both high fat diet and high carb diet increase mortality. The diet associated with the lowest all-cause mortality is somewhere in the middle: ~50% of calories coming from carbs. Again, it’s a U-shaped curve.

So if one tries to lower A1c, that’s great, but just make sure it doesn’t mess up other biomarkers.

100% agree with you on this piece.

This is when an SGLT2i such as empagliflozin or canagliflozin comes in. I’m thinking of adding it to my stack to reduce my HBA1C by 0.5, reduce my blood pressure, improve my cognitive functions, lose a few pounds, and increase my lifespan all for about $0.90 a day.

Why aren’t I taking empagliflozin right now? ![]()

My last HbA1c from Jan 2024 came back at 5.0. That down from 5.5 in Nov 2023 and 5.8 in June 2023. I’m stunned really. That included all the sugary holiday feasts when I put on (and lost) weight. It was a test my doctor wanted related to my metformin prescription.

I’m not sure I believe it. But I’ll keep going with my program to see what another 3 months delivers.

What does everyone think about using Fasting Insulin as an alternative for A1C?