If you fell unconscious in 1950, no one around you would know how to perform CPR: it wouldn’t be invented for another 10 years.1 Or take type 1 diabetes, where survival would involve injecting yourself every day with a thick glass syringe of insulin that was extracted from animal pancreases (with tens of thousands of animals required to produce each pound of insulin). And hundreds of thousands of kids worldwide would catch polio each year, leaving them paralyzed, often needing an iron lung to help them breathe.

Fast forward another thirty years to 1980, and polio would be eliminated in many rich countries through vaccination. Smallpox would be eradicated worldwide. Insulin could now be manufactured by yeast in bulk in bioreactors, and emergency care would look completely different: with implantable pacemakers, AEDs, and coronary bypass surgery.

But you could still die from cancers caused by stomach ulcers, which we now know are typically caused by H. pylori infection and treatable with antibiotics. Or take hepatitis C – a deadly infection that causes liver fibrosis and cancer – which is now curable with antivirals in around 98% of patients.

Some of the most fatal conditions we’ve known, like HIV/AIDS and cystic fibrosis2, are also now highly treatable; taking early treatment for them returns people to near-normal life expectancies. Insulin treatment has advanced to the point that small wearable devices can monitor sugar levels in the blood and release insulin to stabilize them in real time.

But when I read most science journalism, hardly any of it mentions these achievements, the stream of innovation,3 or explains what is still untreatable and why. There’s instead far too much hyping up of preliminary studies – what caused/cured cancer in six mice, for example – and much less about what’s changing people’s lives right now, let alone how much people’s lives have changed over the decades.

So, since last year, I’ve been writing round-ups of the biggest breakthroughs in medicine and putting them into context to give you a sense of where we are. Here’s a link to my post from 2024 in case you’re interested.

Clinical breakthroughs

- Suzetrigine (‘Journavx’) became the first non-opioid painkiller for surgical treatment in decades. In a phase 3 trial of 2,000 patients, it reduced pain as effectively as hydrocodone and paracetamol, but had fewer side effects and doesn’t appear to be addictive. Michelle Ma has written a great article about the history of pain medication leading up to it.

- The second chikungunya vaccine (‘Vimkunya’) was approved in the US and EU; it’s a recombinant ‘virus-like particle’ vaccine. Chikungunya is a disease spread by mosquitoes that is similar to dengue: both can cause weeks to months of joint pain and in rare cases, paralysis. I recently had the vaccine myself because I travel somewhat frequently to India, where chikungunya outbreaks are common; all I got was a slightly sore arm.4

-

Several new lipid-lowering treatments are succeeding in large clinical trials. Some involve designing small interfering RNA (siRNA) to block specific genes from producing their proteins, with just a single injection that has effects for half a year or more.

- Obicetrapib. It cut LDL cholesterol levels by an additional 30% in people with a history of heart disease or familial hypercholesterolemia, who were already on the maximum doses of statins and other cholesterol lowering drugs, in a phase 3 trial of over 2,500 people. The drug inhibits the CETP protein, which moves cholesterol between lipoproteins and the blood.

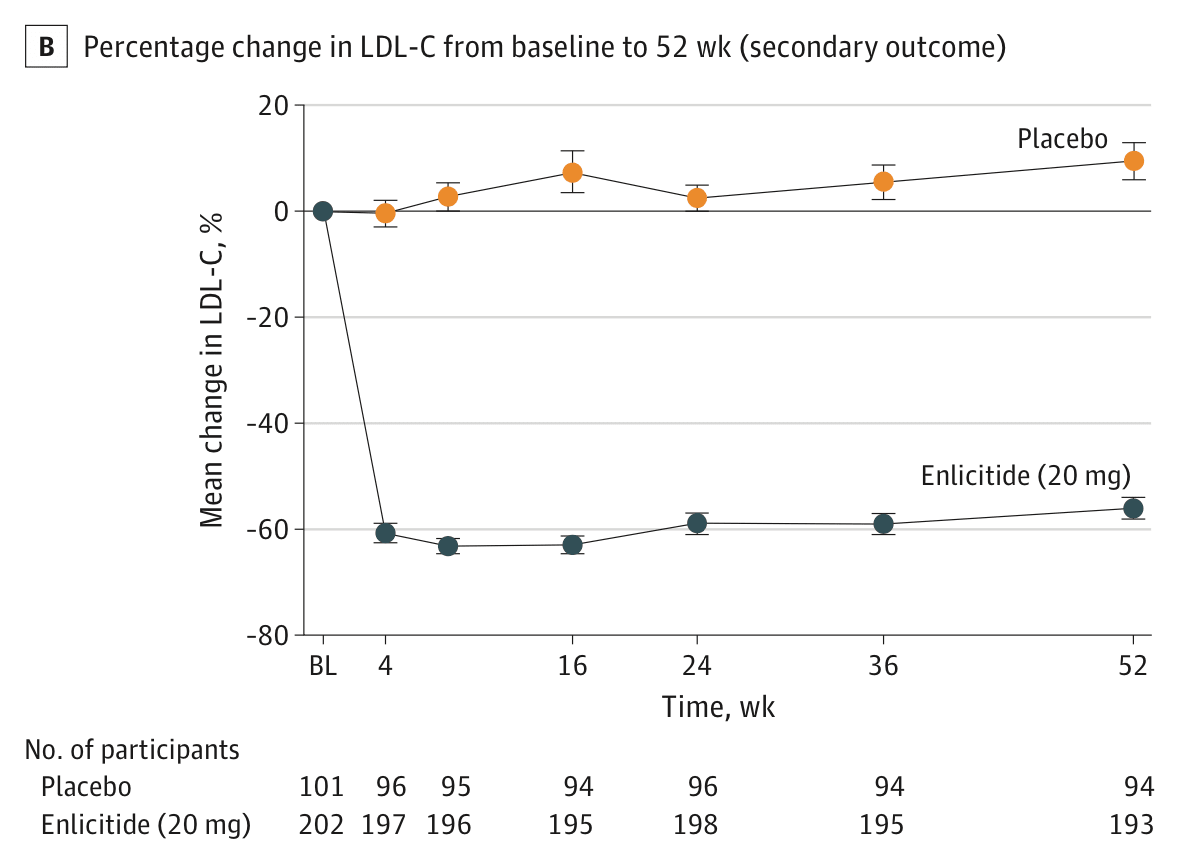

- Enlicitide. It cut LDL cholesterol by an additional 59% in people with hypercholesterolemia who were already taking statins or other lipid-lowering drugs, in a phase 3 trial of over 300 people. Merck is now testing its effect in a broader population. The drug inhibits the PCSK9 protein, which regulates LDL cholesterol uptake and has been a popular target for new cholesterol drugs, but enlicitide is the first to do so in pill form.

LDL cholesterol levels in the phase 3 trial for enlicitide in over 300 people with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, meaning they had an inherited risk for very high levels of blood cholesterol. People taking enlicitide had a 59% reduction in LDL cholesterol compared to the placebo group, 24 weeks after the trial began. Source: Christie M Ballantyne et al. (2025) .

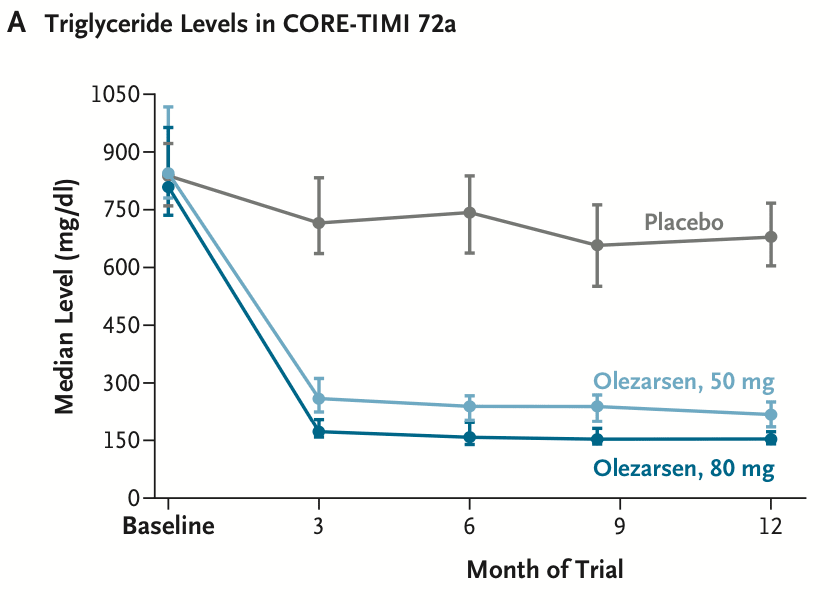

- Olezarsen. It cut triglyceride levels by 50–70% and reduced the rates of pancreatitis episodes by around 85% in people with severe hypertriglyceridemia in a phase 3 trial of over 1,000 people. The drug is an antisense oligonucleotide taken by injection each month, and works by blocking the formation of the ApoC3 protein.

Triglyceride levels in the phase 3 trial for olezarsen in over 1,000 people with severe hypertriglyeridemia, meaning they had triglyceride levels over 500 mg/dL. People taking olezarsen (50mg) had a 63% reduction in triglyceride levels compared to the placebo group, and those taking 80mg had a 72% reduction, 6 months after the trial began. Source: Nicholas A Marston et al. (2025).

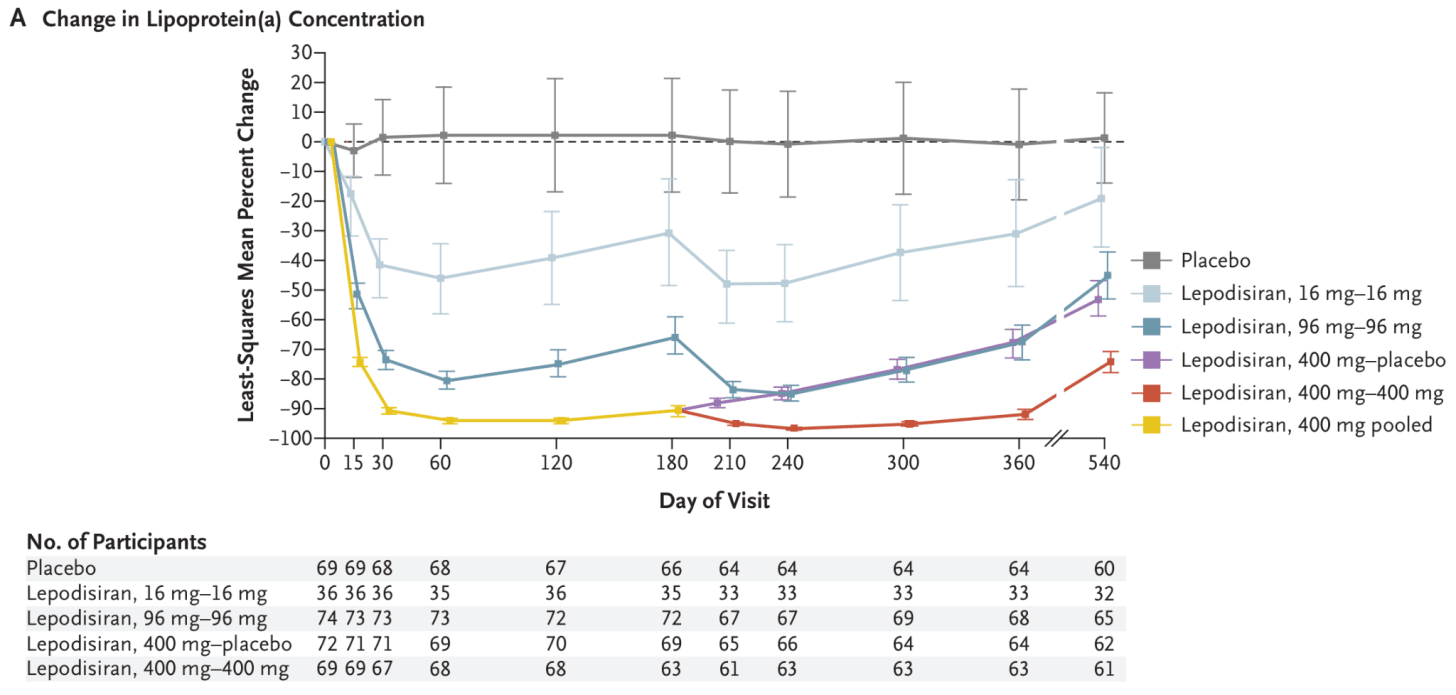

- Lepodisiran , an siRNA drug, causes a dramatic reduction in lipoprotein(a) levels. In a phase 2 trial of over 300 people with very high levels of lipoprotein(a), a single injection of the highest dose (400mg) reduced their lipoprotein(a) levels by 94% and kept them low for months. Their phase 3 trial is ongoing and expected to be completed 4 years from now.

The change in lipoprotein(a) concentration in the phase 2 trial for lepodisiran in people with very high levels of lipoprotein(a), which is like LDL-cholesterol, another risk factor for atherosclerosis. People taking lepodisiran (16mg) had a 41% reduction compared to the placebo group, and those taking 96mg had a 75% reduction, and those taking 400mg had a 94% reduction, 2–6 months after the trial began. Source: Steven E Nissen et al. (2025) .

Read the full story: Medical breakthroughs in 2025 - by Saloni Dattani