That’s the same as I did. When I did the experiments I tried getting maximum amount of the active chemicals by using fresh grapefruit, sliced it up and put it in a blender and drank the contents. That way I got all the chemicals in (aside from the peel of course) as fresh as possible. In addition, to increase the chances of getting a high dose of the active chemicals, I used three different grapefruits and used equal portions of each to get the total amount I drank. This I did to minimize variation between different fruits and to reduce the chances of getting a low dose by chance, because there is always the random chance that you pick a grapefruit that happens to have unusually low amounts of the active compounds. The risk of that averages out to become lower if you use more than one grapefruit.

That describes the observed basic blood PK; it says nothing about what a therapeutic peak level would be, or even if there is such a thing. Lloyd Klickstein, MD, former Chief Science Officer at resTORbio, says that both the therapeutic and side-effects are driven primarily by the trough level, and from my survey of the literature I’m inclined to agree.

Rapamycin only stops processing, during the period of time free from rapamycin, the cell cycle catches up. The quality of processing during the rebound period is critical.

@McAlister is here problematically mixing data from high-bioavailability formulation with data from standard ones. And his two citations for “Direct inhibition of mTORC2” (Halloran et al. 2012) and (Schreiber et al. 2015)) do not appear to demonstrate direct inhibition of mTORC2: they appear fully compatible with the standard model of indirect inhibition due to chronic use leading to reduced mTOR synthesis.

We don’t need a clarification about half-life, because we know their trough levels.

Good catch! That (Halloran et al. 2012) reference should’ve pointed to (Sarbassov et al. 2006). I grabbed the wrong citation. I would edit the original post, but it’s now outside the editing window.

Can you say more about what concerns you here?

My overall intent in that post was to show that we’re not whistling in the dark. “We know enough to design more and less rational dosing schedules.” I focused primarily on avoiding mTORC2 inhibition, but the paragraph you quoted was about a second failure mode we want to avoid—the mTOR rebound. I closed out that paragraph saying: “I suspect this increase in Akt underlies the mTOR rebound sometimes seen with rapamycin, but that’s a topic for another post.” I wrote about it about a month later here: Rapamycin / MTOR Rebound effect in 3/12 non-GF and non-Keto patients - #62 by McAlister

As for the comparison, (Antoch et al. 2020) dosed Rapatar (the high-bioavailability formulation) at ~0.1 mg/kg and ~0.5 mg/kg. It’s worth noting that Rapatar’s bioavailability is only enhanced over unformulated rapamycin:

a single oral administration of Rapatar resulted in 12% bioavailability, which is comparable with commercially available formulations used in clinical practice (Comas et al. 2012)

The FDA label for Rapamune puts the bioavailability for tablets around 17.8% (27% higher than the oral solution’s 14% bioavailability). That makes Rapatar comparable to studies that deliver Rapamune through oral gavage.

I excluded these specifics in the original post because I didn’t think they were relevant to the conclusion ![]() I should also point out that I was comparing the oral Rapatar data with intraperitoneal data, not “with data from standard [formulations]”. The point was to show that high doses inhibit mTORC2, but lower doses (below the threshold of mTORC2 inhibition) can potentially lead to an mTOR rebound.

I should also point out that I was comparing the oral Rapatar data with intraperitoneal data, not “with data from standard [formulations]”. The point was to show that high doses inhibit mTORC2, but lower doses (below the threshold of mTORC2 inhibition) can potentially lead to an mTOR rebound.

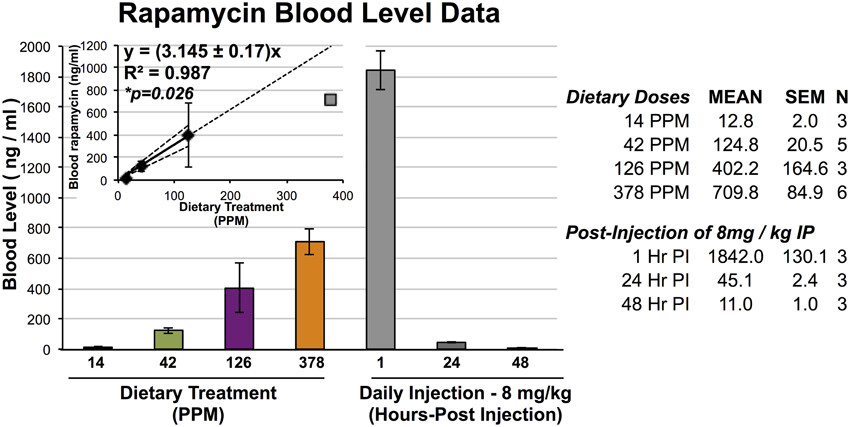

Sarbassov (10 mg/kg) and Schreiber (8 mg/kg) both used intraperitoneal injection, which results in much higher blood levels of rapamycin. Here’s a relevant figure from (Johnson et al. 2015):

Converting PPM to mg/kg (assuming 4g of food consumption and an average 25g mouse) gives us this:

| PPM | mg/kg BW (Approx) | Mean Rapa (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | 2.24 | 12.8 |

| 42 | 6.72 | 124.8 |

| 126 | 20.16 | 402.2 |

| 378 | 60.48 | 709.8 |

Intraperitoneal injection resulted in about an 11-fold increase in rapamycin over a comparable oral dose of encapsulated, food-based Rapamycin (eRapa). The company claims “eRapa consistently provides approximately 30% more drug than generic rapamycin”, but that specific claim is based on unpublished company data.

TLDR: Rapatar’s bioavailability is comparable to Rapamune (and probably eRapa); my conclusion didn’t rely on similar bioavailabilities; I was comparing low and high doses to indicate that inhibiting mTORC2 was not the only failure mode we should try to avoid; confused at what you find problematically mixed ![]()

Happy to nix “direct” from those sentences. Not sure why I included it, to be honest ![]() It makes no difference to my conclusion… which was that our dosing regimens should try to avoid both inhibiting mTORC2 and instigating an mTOR rebound.

It makes no difference to my conclusion… which was that our dosing regimens should try to avoid both inhibiting mTORC2 and instigating an mTOR rebound.

This is incorrect. Rapamycin eventually inhibits the assembly of mTORC2 (Schreiber et al. 2015). I’m not aware of evidence that rapamycin reduces mTOR synthesis. Recycling a quote from my original post:

chronic exposure to rapamycin, while not affecting pre-existing mTORC2, promotes rapamycin inhibition of free mTOR molecules, thus inhibiting the formation of new mTORC2 (Sarbassov et al. 2006)

As with most things in biology, the mechanism is actually more complex. For example, in human rhabdomyosarcoma Rh30 cells, rapamycin inhibited the phosphorylation of mSIN1 (an mTORC2 component) within two hours and at very low concentrations (0.05 ng/ml) (Luo et al. 2015). This is distinct from rapamycin sequestering free mTOR.

Luo’s results built on (Rosner and Hengstschläger 2008), who showed that rapamycin triggered the dephosphorylation of rictor and mSIN1 (both mTORC2 components), followed by a translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. This dephosphorylation and translocation resulted in a cytoplasmic rictor/mSIN1.1 complex that is not bound to mTOR. The end result is less mTORC2 assembly.

What is the issue with temporary over activation of mTOR?

Sorry for very late reply. We do monthly safety labs x 3 and then if stable can decrease to quarterly.

Bryan Johnson quits rapamycin because of the side effects: Anti-aging guru Bryan Johnson ditches controversial drug after infections

Hi, I am new here, so forgive my naive question: you talk of “20 mg equivalence (6 mg + GFJ)”. What is GFJ ?

Thank you

GFJ = Grapefruit juice

Hello DeStrider,

20 mg equivalence (6 mg + GFJ) would imply drinking GFJ continuosly for several days to mantain inhibition of 3A4. Is this how you do it ?

Thank you, Maxi

Its not that long. There are a number of inhibitors GFJ, Pomelo and pomegranate. The assumption of a x3.5 factor of biolavailoabilty is probably ok.

You only need to drink grapefruit juice 1-4 hours before you take Rapamycin to get the multiplied effect. In my case, I eat two grapefruits 1-3 hours beforehand.

Due to side effects, I’ve switched to 14 mg equivalent (4 mg + GFJ) for two weeks and then one week off. That seems best for me.

GFJ inhibits in the lining of the gut only. CYP3A4 also works in the liver, but GFJ doesn’t get there well enough to do any good, so it just helps absorption. This is my understanding.

Its uaeful for bioavailability. I would be concerned in inhibiting metabolism as that could extend the half life.

Hello, I am new here hence so late on your post. I have severe chronic muscle pain and fatigue (ME/CFS,IBM) and I am starting Rapamycin 6 mg/week in the hope it helps. Could you please give more info on the chronic pain and Rapa effect ? Did lower doses than 7mg+GFJ also help ? Tnx

Hi Maxi,

I recommend starting with a lower dose and gradually increasing it to 6mg per week. This way, you can monitor any side effects and see how they interact with your conditions. Perhaps begin at 1mg per week and increase by 1mg each week until you reach 6mg, then assess your situation from there. This is the approach I took.

It’s hard to determine for sure if it’s helped my condition. Sometimes days after a dose, I feel it was beneficial, but I can’t dismiss the placebo effect, and I’m still managing my illness, so no miracles yet. Rapamycin is a powerful molecule, but its positive effects might go largely unnoticed.

Currently, I’m taking 5mg with grapefruit juice every 15-16 days. Given that I’m also APOE4/4, I believe the potential benefits outweigh the risks, as I’m actively trying to prevent any cognitive impairment. However, it’s crucial for each of us to conduct our own risk-reward analysis.

You’re definitely in the right place to make an informed decision. Good luck and let us know if there’s any more questions.

Dumb question and I’m not a doctor, but are you on a statin?

No, I take only blood pressure medications and muscle relaxants/pain killer because of my chronic deseases (ME/CFS,IBD). I am just starting Rapa 6mg/week in the hope it helps.