There’s also a walking version of this, Oura uses it to estimate vo2max

Ok, got it, now where is the chart that says how long I’ll live?

Survival of the fittest? Peak oxygen uptake and all-cause mortality among older adults in Norway !

Conclusion

The Grim Reaper typically targets individuals with VO2peak levels <26.5 mL/kg/min/ and <22.2 mL/kg/min when chasing male and female souls aged 70–77 years, respectively, reflecting his penchant for limited CRF. These data underscore the importance of maintaining or enhancing CRF throughout life, providing clear targets for clinicians in assessing patient CRF levels.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the VO2peak levels that older men and women should strive to reach to reduce risk of facing Death, which is of clear importance for public health. The main findings among men and women 70–77 years of age at baseline were that: 1) compared to having a VO2peak < 85 % of the sex-specific average, a VO2peak ≥ 85 % lowers the risk of being caught by Death by 66 % in men and by 59 % in women, with no additional risk-reduction among those

Paper:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0033062024001695

Survival of the fittest Peak oxygen uptake and all-cause mortality among older adults in Norway.pdf (2.1 MB)

How difficult is it to find genes that increase VO2Max and see how that affects longevity?

Despite being a strong predictor of mortality, VO2max is not causally associated with T2D or longevity.

It makes sense to me that it affects quality of life though. I don’t have any evidence for that. I’m not sure what to search for?

VO2 Max and Genetics

We’ve known for a while—since studies on identical twins in the 1970s—that some individuals naturally have a higher VO2 max because of their genetics. Researchers have found that VO2 max is more similar within related families, both on its own and even after training.

More recently, scientists have identified almost 100 genes related to VO2 max, and specifically related to VO2 max trainability (your ability to improve cardiorespiratory fitness). One genetic variant (rs6552828) located in the ACSL1gene is predictive of a person’s ability to improve their VO2 max through exercise. Researchers continue to study if this gene is a factor in the success of elite athletes.

Source:

Related:

Genetic Connection between Aerobic Fitness and Disease Is Not What You’d Expect

Gene variations associated with greater VO2 max also linked to biomarker for kidney function, diabetes and heart inflammation

New research examines the complex relationship between gene variants, cardiorespiratory fitness and the development of chronic disease. The study is published ahead of print in Physiological Genomics. It was chosen as an APSselect article for October.

“We discovered that genotypes associated with higher VO2 max were associated with a higher risk of disease.”

Researchers examined data from the Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT). HUNT is a long-term analysis of the population of the Norwegian county of Trøndelag. HUNT includes both questionnaire responses and clinical data. Its data can also be linked to hospital disease classification codes from local hospitals.

The researchers built on a previously published first-of-its-kind genome-wide association study that looked at a subset of HUNT participants who also took part in tests of their maximum oxygen consumption while exercising (VO2 max). VO2 max is a common measure of aerobic fitness, with higher values indicating a lower disease risk.

Thank you, RapAdmin for posting this article. This is such an important finding. A lot of health and longevity research is confounded by genetic variants and environmental factors. Exercise is a great example. You may have greater exercise capacity genetically, and also need that exercise more, because that greater exercise capacity is also genetically linked with more disease vulnerability. You then get a bunch of folks who exercise and they are healthy because it fixes their disease vulnerability, while folks who don’t exercise and have that disease vulnerability fall sick. You then conclude that exercising is healthy. It is, but it works best exactly in the folks who need it most. If I own a car (disease vulnerability), I will benefit from buying insurance (exercising) compared to someone with a car (disease vulnerability), but no car insurance (not exrecising). But if I don’t own a car, I won’t benefit from buying car insurance. That’s how you get all those centenarians and supercentenarians who don’t do focused exercise, or even have contempt for exercise (like the recent news about a healthy 110 year old man 1*) yet who live long and often healthy lives.

The bottom line is that true longevity interventions must move in the direction of personalized medicine. Everyone is an individual, everyone has their own response to drugs, supplements, diet, exercise, lifestyle. Yes, there may be majorities or trends this way or that, with any response to interventions, but we remain unique individuals at the end of the day. An intervention X may work in 80%, 90%, 99% of the people, but someone must make up that remaining 20%, 10%, 1% and that may very well be you.

1* 110-year-old NJ man who lives on his own and drives daily offers tips on longevity

Some qoutes:

"He lives alone with no home aide or extra help, cooks simple food for himself, walks up and down his three-level house and drives “pretty good” daily with no issues.

He’s never had cancer, dementia or other major diseases and has no headaches or backaches.

But Dransfield, who was born in 1914, isn’t a health fanatic.

He smoked cigarettes for 20 years and worked his whole life from age 15 to his late 70s. He eats whatever he likes — including hamburgers, milk chocolate and Italian food, has an occasional beer, drinks coffee every day and is amused by people who run."

As, always, kids, it is better to be lucky than good.

That “not a health fanatic” guy has lived a longer life with smoking, beers, hamburgers, indifferent diet, no “exercise”, than likely (statistically) anyone reading this website will, who is a health fanatic and invests oodles of time, money and effort into diet, exercise, supplements, exotic drugs and exotic treatments.

So, should we keep doing what we’re doing? Yep, that’s what the statistics tell us, so we go with those 80% or whatever. Most of us can’t count on being the 1% or the 0.000000001%. At the same time, we must stay humble and acknowledge that it all comes down to your individual self, what is best for you, and the cards you were dealt.

Hate that they just put “track and field running,” since that one category by itself almost spans the rest of the range here. I’m guessing there’s a large difference between the 100 and 200 m specialists vs the 10K guys.

My VO2 max has a life of its own. Goes up and down (maybe within margin of error on Apple Watch) without any clear correlation to other activity. I do Norwegian HIITs 3 times a week, zone 2 cardio etc etc

Same with HRV. Very variable.

Im with Inside Tracker and their ‘pro tip’ today was to reduce creatine to increase VO2 max. Hadnt heard that. Have been taking 5g of Creatine for years.

Anyone noticed blunting of VO2 due to creatine?

I thought you liked working out.

Hahaha - noooo! I do not like working out. The best part of the workout is the final set. And, knowing I do not have to go back for a whole day. Seriously!

That said - I do like the way I look, the anti-aging benefits and general strength and feeling healthy - so not going to the gym is really not an option. I also think the TRT definitely makes it easier.

I go religiously, 1 hour and 15 minutes - non-stop. But, I have been waiting for the day it kicks in that I look forward to it. Now going on 8 straight years of every other day not thinking that will happen.

LOL, that me! I actually dislike exercising, but do it religiously, because I know it has health benefits. I always look forward to my days off from exercise, as it is only then that I feel fully alive - Wednesday, Saturday, Sunday, even though the off days are not 100% off, since I still do 45 minutes of brisk walking on those days.

And the best part of exercising is when it’s over, and I can take a shower. Too bad I don’t believe there’s ever going to be a pill that duplicates the effect of exercise 100%, because I’d be the biggest customer.

The inestimable Dr. Greger comes through again, slashing away at sacred cows with no regard for the sanity of exercise worshippers like Peter Attia. Very hard to argue against the, at this point self-evident, conclusion that it’s the genes uber alles. And a good antidote to all the exercise fanatics of “the more the better”. My own view is that you obtain all health and longevity benefits from relatively modest exercise levels, levels that may seem shockingly low to exercise advocates. Doing more than that relatively low minimum might give some functional benefits, if, say, you simply enjoy challenging sports or recreational activities, but no further longevity benefits (though possible premature mortality benefits?). Doing a great deal more, well, you’re on your own there, in the club of those who are fans of extreme sports and activities and are willing to pay the price - to each their own.

Exercise as Medicine (Part 2)

I think Greger is dangerous and it is not helpful to listen to him at all even if he sometimes is correct.

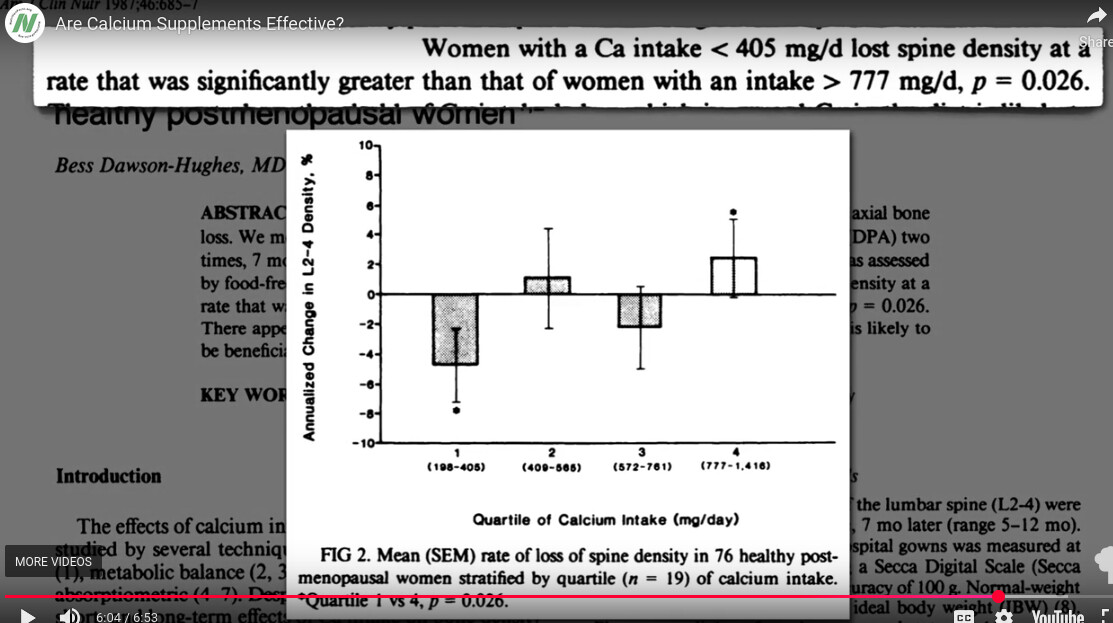

For example, on calcium supplements he said that in the hundreds of mg calcium intake, bone loss was happening. He totally ignored the fact that the same graph showed a trend towards improvement in bone health at higher intake and didn’t mention this. The study also compares it with above 700 mg intake which he didn’t mention, instead made it sound like you’re safe above 400 mg.

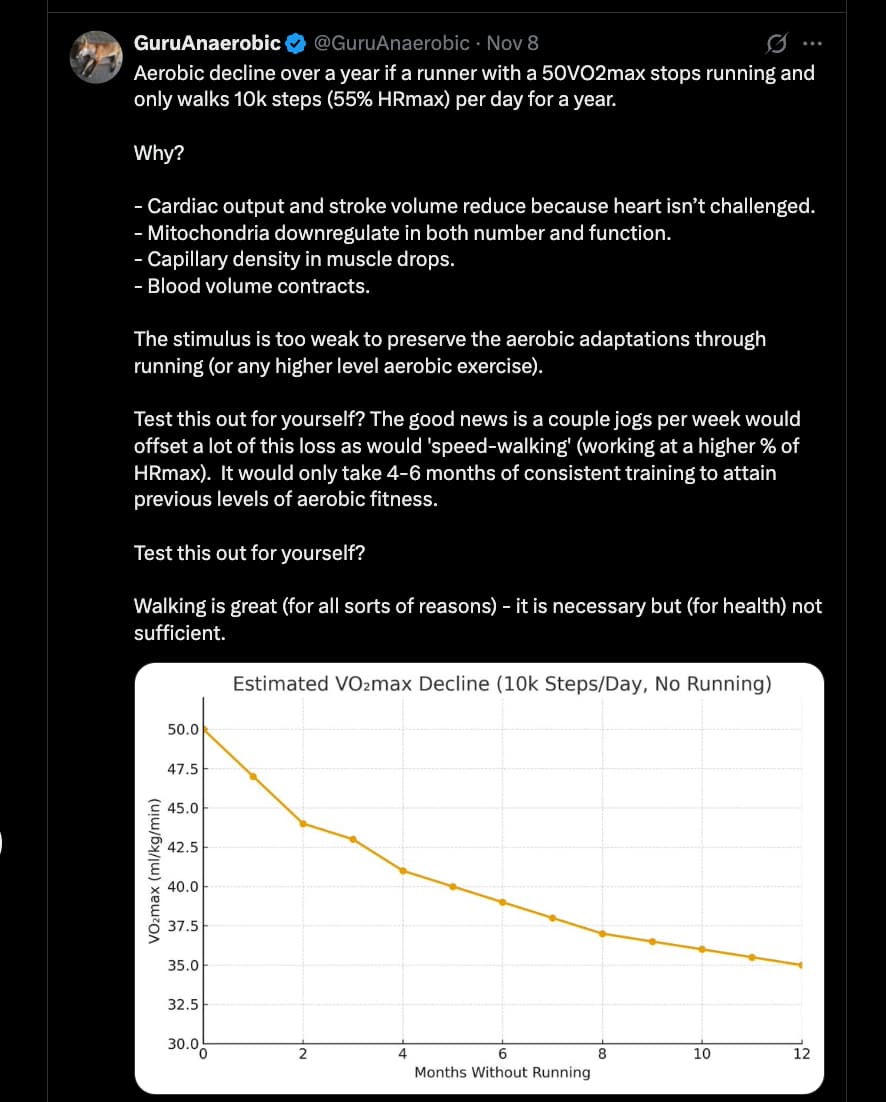

I found this really interesting… and disappointing ![]()

Source: https://x.com/GuruAnaerobic/status/1987386660108034343?s=20

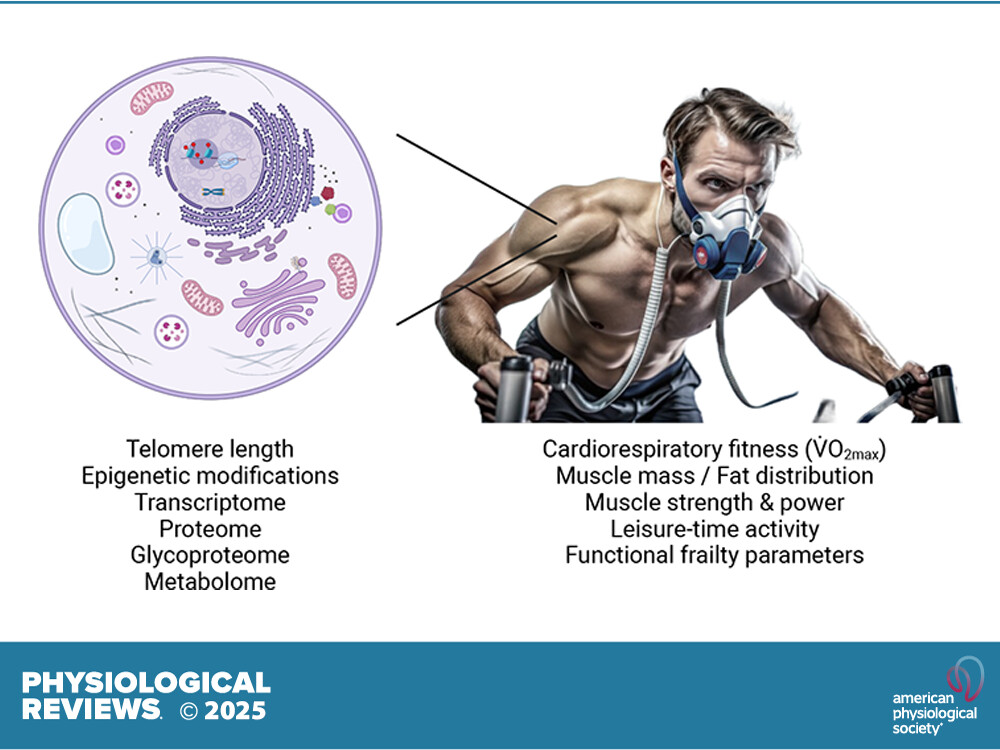

Review article (Open access):

Biomarkers of aging: from molecules and surrogates to physiology and function

6.1. V̇o2max/Cardiorespiratory Fitness

6.1.1. V̇o2max: principle and testing.

At the moment, cardiorespiratory fitness is the most studied and best predictor of morbidity and all-cause as well as disease-related mortality (FIGURE 5, A AND B) (572–583). Cardiorespiratory fitness is assessed by measuring the maximal rate of oxygen consumption (V̇o2max). This concept was introduced by Archibald Hill and Hartley Lupton in 1923 (584) and has been developed ever since (585, 586). V̇o2max, sometimes also reported as V̇o2peak [the highest recorded V̇o2 in tests failing to reach a V̇o2max plateau, therefore potentially underestimating the true maximum (587, 588)], is a readout obtained in cardiopulmonary exercise tests that correlates with cardiorespiratory fitness and endurance capacity (589–593). Most often, V̇o2max, either reported as an absolute rate (mL/min) or normalized to body mass (mL/min/kg) (sometimes also normalized to lean body or skeletal muscle mass), is typically determined in graded maximal exercise tests by measuring ventilation and respiratory O2 concentrations (reaching a plateau), often combined with determination of blood lactate concentrations (e.g., approaching or exceeding 10.0 mmol/L), heart rate (reaching a plateau), respiratory exchange ratio (RER; ≥1.1), and perceived exertion [e.g., 19–20 on the Borg scale from 6 to 20 or 9–10 on a Borg Category-Ratio 10 (CR10) scale from 1 to 10], even though variations between protocols for some of these thresholds exist (594–596). The results depend on the exercise modality: treadmills or cycle ergometers are commonly used, but V̇o2max values can be acquired in any exercise setting that is amenable to breath-based oxygen analysis, e.g., rowing ergometers, all of which involve different sets of muscles. The V̇o2max often differs between testing modalities and prior task habituation: for example, runners might reach higher values on the treadmill, whereas cyclists or triathletes can excel on cycle ergometers (597). The choice of testing paradigm therefore depends on availability, practicality, intention for assessing task specificity, coadministration of other tests (for example, electrocardiography might be easier on cycle ergometers because of minimal upper body movement), and other factors.

V̇o2max integrates functional aspects of a number of organs and tissues that contribute to oxygen intake, distribution, extraction, and usage (FIGURE 5C) (598). Intake is affected by pulmonary capacity and function, in part depending on respiratory muscle functional capacity, which can be improved by specific training even in older adults (599). Distribution combines cardiac output parameters, oxygen carrying capacity by red blood cells, blood volume, and vascular properties. Extraction and usage, at least in the case of cardiopulmonary exercise tests, are mainly determined by the degree of tissue vascularization (hence the proximity of blood vessels and muscle cells), intramyofibrillar trapping of oxygen by myoglobin, and the rates of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. The rate-limiting step that determines V̇o2max can be variable and, for example, shift depending on the training state, from oxygen usage in muscle fibers in the untrained to oxygen provisioning by cardiac output and tissue vascularization in trained athletes.

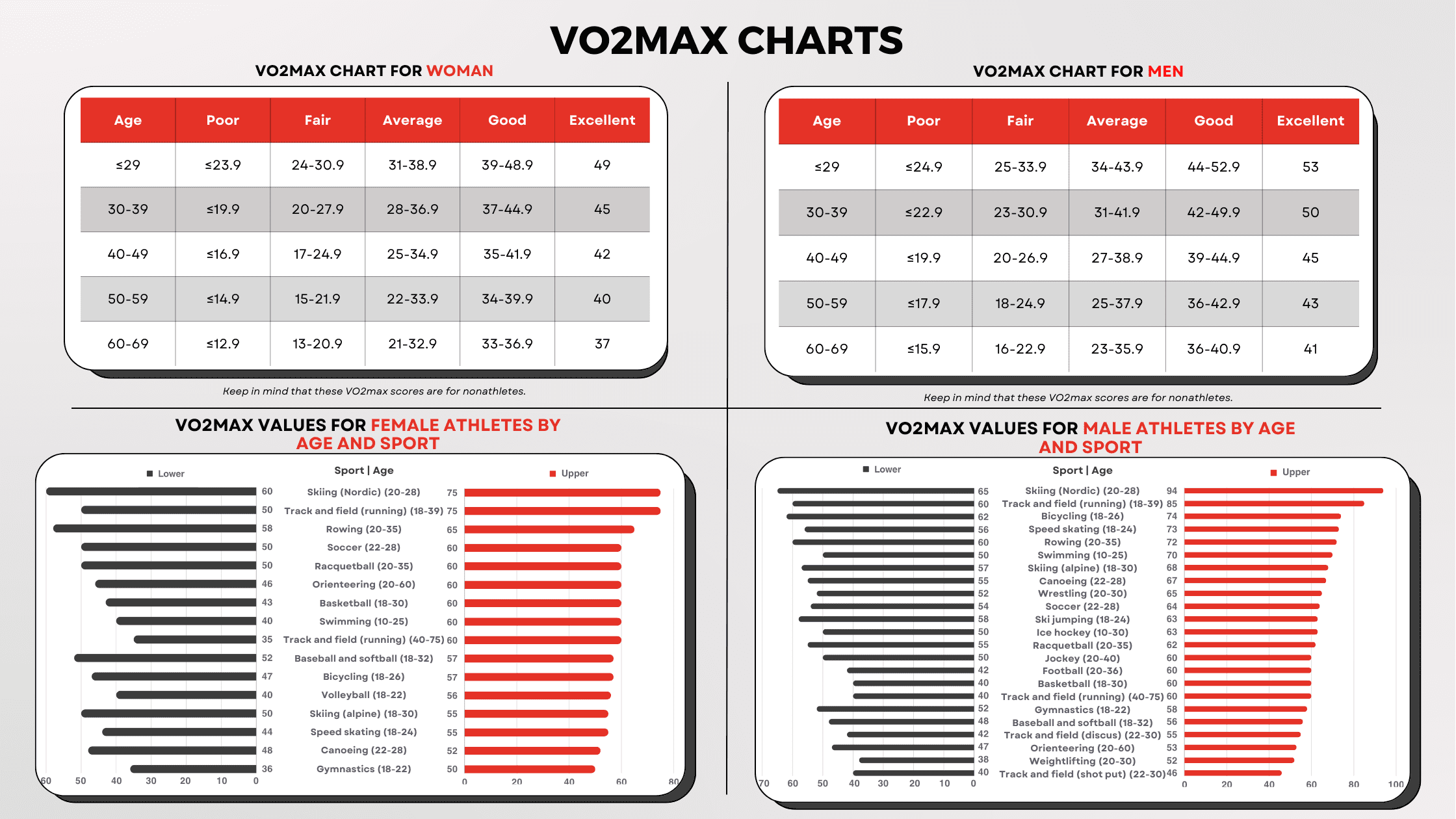

6.1.2. V̇o2max: age dependence and health/mortality prediction.

V̇o2max decreases progressively with age, at a rate of ∼7–10% per decade (corresponding to 4–4.6 mL/min/kg) (571, 600, 601), down to an “aerobic frailty threshold” of 17.5–18.0 mL/min/kg that is required for an independent lifestyle (574, 602, 603). At this point, individuals have to utilize almost their maximum aerobic capacity for tasks related to daily life and independence, associated with severe physical fatigability (604). In the worst case, this deterioration continues to fall below 10.5 mL/min/kg, when ∼30% of oxygen is used to maintain basal metabolic rate, potentially leading to fatal outcomes (574, 602). Accordingly, the assessment of V̇o2max constitutes a strong and independent predictor of morbidity and mortality in different populations, young and old, healthy and clinical (574, 576, 605). In fact, this strong link with mortality and various chronic conditions including heart failure, hypertension, stroke, chronic kidney disease, dementia, and depression was consistently demonstrated in an overview of meta-analyses that included >20.9 million observations (576). More specifically, having a low cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with a 41–53% higher relative risk for all-cause mortality compared to those with a high cardiorespiratory fitness (606). Strikingly, even in unfavorable conditions, such as abnormal glycemic status (607) or obesity, being fit is a strong predictor for reduced all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality (608–611). In fact, relatively fit obese men (top 80% of the age-specific cardiorespiratory fitness) have a 50% lower cardiovascular disease mortality risk compared to normal-weight unfit men (lowest 20% of the age-specific cardiorespiratory fitness) (609). Indeed, cardiorespiratory fitness can mitigate risks of obesity in a significant manner, beyond those of unfit, normal-weight individuals (612). Similarly, high cardiorespiratory fitness can overcome an unfavorable genetic predisposition for dementia (613). Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness is a strong inverse predictor of heart failure risk irrespective of BMI (614). Importantly, even though up to 50% of the variability in V̇o2max in sedentary individuals is estimated to be of genetic origin (615) as well as other biological and methodological factors (616), trajectories can be strongly affected by exercise at young and old age (617–622), and even a moderate increase by 3.5 mL/min/kg [1 metabolic equivalent of task (MET)], achievable after 2–3 mo of training (602), reduces the risk of heart failure by 18% (572) and all-cause mortality by 11–17% (576, 606). Interestingly, despite exhibiting lower V̇o2max values, older athletes can reach high performance levels due to the ability to perform work closer to the V̇o2max compared to younger counterparts (623). Lifelong exercise habits provide most benefits to mitigate age-related declines in V̇o2max (624) and can confer benefits in old age (625). However, even in the very old, cardiorespiratory fitness can be improved, as exemplified in the case study of a 101-yr-old cyclist (626).

On the topic of cardio fitness in general, if you want to keep more of your fitness, ditch metformin

Met[formin] blunts exercise training-mediated increases in vascular insulin sensitivity at the levels of conduit arteries and capillaries, in parallel with altered inflammation and glycemic benefits.

Exactly this happened to me. My VO2max used to be 48, but after I had surgery and had to stop running, it dropped to 38 in a year or so. I still walk about 10k steps a day and use my bike instead of the car whenever possible, but it clearly isn’t enough to maintain it.

I’m about to start training again and add some running back into my workouts, and I’m hoping to regain at least some of that VO2max.

I’m about to have surgery and will be unable to exercise for a few weeks at least. I also had to stop exercising because of spinal disc problems (hence surgery) for a couple of months, and I could tell my conditioning absolutely collapsed. Muscle decline was even more stark. Just a couple of months ago I was doing very strenuous squats including jumping squats with a 45lbs weight vest, and now I’m winded after 5 minutes of bodyweight squats.

I have noticed that with advancing age (I’m 67), you decondition extremely rapidly. When younger I could stop exercising and the decline in exercise capacity would be quite gradual. Now I stop exercising and my conditioning falls off a cliff.

Now that the diagnosis has been made, and a surgery date set for late December, I’ve resumed some exercise specially modified to spare the spine, because I will be immobilized for many weeks after the surgery and I don’t want to emerge from this with sarcopenia and frailty. I’m trying to build up some reserve.

As has been observed, older people decline in stages. There’s an event, you decline some and regain only part of your previous physical capacity. Then there’s another event and you decline further and so on. The trick is to try to regain your full exercise capacity after an event. That is what I am determined to do. I may have to adjust my exercise protocol, but I must do all I can to get back to 100% of my previous capacity.

For example, right now I cannot jog for longer than about 10 minutes due to spine issues. So instead, I’m doing a series of “high knees” intervals. It’s incredibly taxing on your cardio, I at present cannot do more than about 15 seconds in an interval (with proper form and max effort). So I do about 5 of those a day. I’m hoping to gradually increase the intervals, so in a few weeks before the surgery I’m at least in better shape and not like a human jellyfish. We’ll see.

Bottom line: you must fight to get your VO2Max back to a higher level and not allow an event (like surgery) to permanently set at a lower level. With age there will be a gradual decline anyway, but you try to avoid sharp drop offs after forced episodes of non-exercise.

After surgery and recovery, that will be my challenge. I must get back 100% of my conditioning and muscle strength and power. I am absolutely determined to meet that challenge.