Artery-Clogging Plaque?

A commenter wonders about the difference between stable and unstable plaque.

If I understand you correctly, stable plaque isn’t something to worry about. But isn’t one danger of plaque that it builds up over time and eventually clogs the entire artery? Thus if you continued to get more and more “stable plaque,” couldn’t this create problems eventually if it were to fill the entire artery?

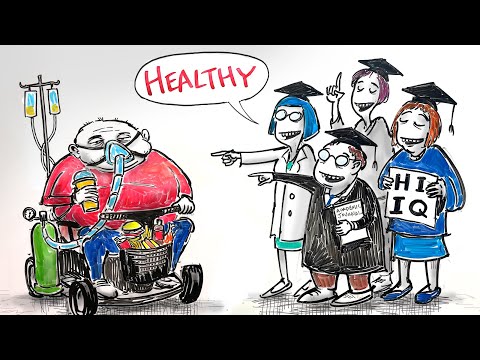

Many people think of plaque-filled arteries as being like clogged pipes. The plaque continues to grow until it occupies the entire lumen or opening through the artery. When it does grow big enough to occlude the artery and shuts off blood flow to heart tissue downstream, then that downstream tissue dies, an event we call a heart attack. That description makes a nice story and sounds plausible, but that’s not what really happens.

The plaque forms beneath the inner lining of the artery. As it grows, it can make a sort of bulge of the artery that intrudes a bit into the lumen, but the artery itself can expand and make a larger opening for the blood to flow through. As long as there exists a large enough channel to accommodate enough blood flow to the downstream tissues there isn’t a problem.

The plaque itself, which lies beneath the inner layer of the artery lining can be thought of almost as a large pimple or boil, composed of all kinds of sticky material. (How this happens would take a book to explain. Fortunately, Malcolm Kendrick wrote an easy-to-read book that explains it all nicely titled The Clot Thickens, which I highly recommend.)

If you think of this soft, goo-filled plaque as being kind of like an inflamed pimple, you can kind of get the idea. If the plaque bursts open and releases this inflammatory junk into the blood coursing through the artery, all hell breaks loose. The immune cells in the blood try to patch the leak. They recruit platelets, which accumulate and can form a sort of clot/scab. If this clot/scab breaks loose and floats downstream, that is what causes the occlusion.

Now if the body begins to repair this soft or unstable plaque by beating down the inflammation and shoring up the plaque with calcium, the soft plaque becomes hard or stable plaque, which is vastly less prone to rupture.

In the study of the Masai autopsies by George Mann I wrote about last week, the coronary arteries involved had plenty of hard plaque, but the opening through the arteries, the lumen, were wide open. Which is why the Masai did not experience heart disease (ie heart attack) despite having plenty of plaque.

You can stabilize plaque in a couple of ways. One way, strangely enough, is with statins. Apparently statins do stabilize plaque, probably by reducing a bit of the inflammation. Which is doubtless why those study subjects on statins experienced fewer fatal and non-fatal heart attacks as compared to those control subjects who didn’t take statins. But, on the whole, they didn’t live any longer. Which means the statins caused enough of them to die from some other cause to cancel out the modest benefit of reducing the number of heart attacks.

People get coronary calcium scans (CAC), find out they’ve got a lot of plaque, get put on a statin, and come back in a year or two for a repeat scan and discover that their scores worsened. So clearly they aren’t a certain cure for plaque.

Another way I believe plaque can be stabilized is with a low-carb diet. I discovered this from a long-time commenter on my blog. He was a real fan until he wasn’t. He commented positively about everything, then one day, he turned on me. After that, he had nothing positive to say and everything was a critique. I ended up reaching out to him to ask him why the change of heart.

He wrote back and said he had trusted me, and I had let him down. He wrote that he had gotten a bad CAC score and, based on the recommendations I had made on my blog and in our books, he went on a low-carb diet in an effort to lower his CAC score. When he went back a year later for a repeat, his score had gone up. And he was pissed.

I asked him to send me his score, which he did. I interpreted it as per the technique I wrote about last week and found him to be in the quartile who had the least risk. He was not placated. He went back to a low-fat diet, and I haven’t heard from him since. I suspect I never will.

I had a few other similar experiences—not of someone being an asshole, but of people who had their CAC scores go up a bit after switching to a low-carb diet. I had one patient who is a close friend of mine end up with a hugely elevated CAC score. I was a little worried about recommending a low-carb diet to him, so before I did, I reached out to Bill Davis, who before he got all into Wheat Belly and anti-gluten, wrote a book on calcium scanning and plaque reversal.

I told him about the dilemma with my friend. He told me that after he started putting his patients (all of them heart patients as he is a cardiologist) on low-carb diets, his life had changed. He said he got to spend his nights at home instead of at the hospital because he didn’t see heart attacks any longer. He said he still saw horrible CAC scores and still saw terrible lipid levels, but that he didn’t see heart attacks.

That conversation along with my experience with the new way of calculating risk combined with the aggregate experience MD and I had with patients, made me comfortable using a low-carb diet in folks with high CAC scores. MD and I treated many, many patients over the years with low-carb diets. Most of them were middle-aged folks with bad lipid levels, high blood pressure, and even diabetes. Patients stayed with our program for many months. If you take the number of patients we had times the amount of time they spent with us, it turns out to be many thousands of patient-weeks. And these were patient weeks of people who were at high risk for heart disease given their age and co-morbidities. Yet we never had one of our active patients who had a heart attack.

More on Statins

I received the next couple of responses from readers. They go along with the many stories I’ve heard from my own patients who have been put on statins.

Hate to beat a dead horse (statins), but check out the former rugby player who was told he had terminal nuero issues, so he quit statins, and guess what - he recovered. Paul Gill from Leeds UK. If this link doesn’t work google his story. Big question is with the platoon of physicians, why did not one of them say: maybe it’s the statins? Ugh! https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/health/former-rugby-player-from-yorkshire-diagnosed-with-mnd-discovers-symptoms-were-caused-by-statin-pills-4509761

This one via email.

As a Statin side-effected individual, I feel the need to share some acquired insight on Statin drugs for the benefit of your subscribers.

Statins are a category of CoA Reductase inhibitors that essentially “Gird” the Mevalonate pathway to inhibit the production of an enzyme needed to produce cholesterol. This pathway is also an essential avenue for the production of Heme-A, Dolichols, and Ubiquinol; all of which are necessary to good health, and all of which are likewise inhibited.

At least one of the drugs used to achieve this effect, Lipitor, is able to cross the blood/brain barrier and enter the brain itself. The brain is, in its makeup, essentially a trove of cholesterol, and who knows what the effect of this pharmaceutical exchange in this environment might be?

CoA reductase inhibitors can also interfere with transporter pathway slc01b1.

Having SLCO1B1 decreased function means that you may have reduced transport of certain medications into the liver for processing and removal from the body. This may lead to higher than normal medication (Statin) levels in the body.

I can tell you from first-hand experience how potentially destructive Statins an be, as I was placed on a Lipitor regimen in early 2000 after my PCP at the time found my total cholesterol was dangerously high at 220. I was a typical medical “lemming”, and I took the medication as prescribed. In two months I was in pain from head to toe, had difficulty walking and was only comfortable in a recliner. Prior to this I went to the gym three times a week, played frisbee golf and volleyball, and Kayaked on a lake near my home in Colleyville, Texas. After some months of follow-up, I went to a physician, a family friend, who picked up a tome she referred to as the Physicians’ Desk Reference, and looking up the Statin drug, Lipitor, began to read aloud all the problems I was experiencing. I stopped the drugs and found a website hosted by Dr. Duane Gravline, a NASA physician who had also been side-effected (https://spacedoc.com/). The rest of this story is a journey of self-education and partial recovery which I won’t relate here. Suffice to say I am now an adamantly vocal critic of cholesterol management. I recommend Dr Graveline’s website category “Spacedoc Forum” to any and all.

I communicated with Dr. Graveline years ago. He is no longer with us. He died ~ten years or so ago. He went on statins while in NASA and got complete amnesia. He recovered when he went off the drug, but the docs at NASA put him on a lower dose, after which the symptoms returned. He ended up devoting most of his time to his spacedoc writings. He had kind of a checkered past, but he was definitely injured by statins and wanted to get his story out.

I’m posting the correspondence from these two people just to demonstrate that statins are not without issues. In some cases, very serious issues. Although many people take them and seem to experience no problems, on the whole, they are not benign drugs. At least not in my opinion.

Especially since they are given to lower LDL levels to prevent heart disease, and LDL has never been shown to cause heart disease.