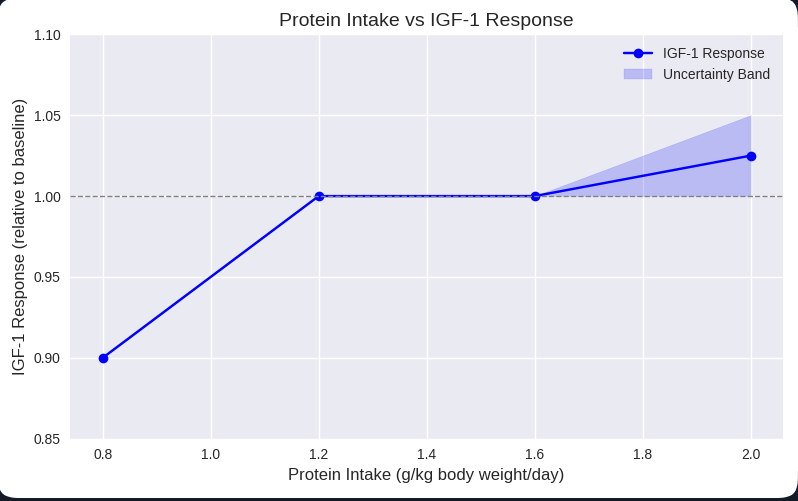

Interesting graph. I am not sure what evidence they are using to claim that flat part of the graph is the “optimal” IGF-1 response. Statement seems to describe optimal muscle growth but muscle growth does necessarily equates longevity. In fact the Blue Zones (YES, I know - CONTROVERSIAL) centenarians appear to consume only about 1 gram/kg at most. To anyone that visited the Mediterranean (Italy, Spain, Southern France), Latin countries or Asia and had the privilege to dine with the locals this is pretty apparent. So they would fall on the left side of that graph with IGF under 1.0 relative response. Anabolic response is a double edge sword whether it comes from sex hormone, m-TOR or IGF-1. It promotes growth of muscle, skin, bone…or fibrosis, tumors or tissue hyperplasia (like prostate). This process seems more regulated when we are young but it becomes more chaotic with age. These anabolic levers have to better managed as we get older.

Personally, I end up eating about 1.4 g/kg thru mostly plant based diet with yogurt, some eggs and cheese, occasional fish and rare meat. I do about 10-12 of cardio (cycling, running or pickleball) and 2-3 h of resistance per week. My appetite is pretty high and I end up eating probably a bit too much. Probably if my appetite was curbed a bit, I would end up eating closer to 1.0-1.2 g/kg. This happens when I travel and don’t exercise so intensely. Interestingly this happens almost automatically by following green Med type of diet, I don’t purposely seek out protein.

Here are my AI findings:

Lowering IGF-1 (Insulin-like growth factor 1) may increase longevity, particularly in cases of high IGF-1 levels, based on evidence from animal studies and populations with exceptional longevity. However, the relationship is complex, as studies in the general population show mixed results, with some even suggesting both very high and very low levels are associated with a shorter lifespan. Excessively low IGF-1 can be linked to various health issues, so moderation is key, and the effect appears to be gender-specific in some cases, with females often benefiting more from lower levels.

Evidence for a link between lower IGF-1 and longevity

- Animal studies: Down-regulating the IGF-1 pathway in mice has been shown to significantly prolong lifespan.

- Genetics: Individuals with specific gene mutations that cause relative IGF-1 resistance often have exceptional longevity.

- Population studies: Low IGF-1 levels have been associated with longer survival, better cognitive function, and better overall functional status in some populations, particularly in the very old and those with a history of cancer.* Centenarians: People who live to 100 years or older tend to have lower IGF-1 levels than their offspring.

Complexities and caveats

- Reverse causation: In the general population, low IGF-1 levels may not be the cause of poor health, but rather a symptom of it. Illnesses can lead to a drop in IGF-1, making it appear that low levels are harmful when it is the disease that is the primary problem.

- U-shaped curve: Some studies have shown a “U-shaped” relationship, where both very high and very low IGF-1 levels are associated with a shorter lifespan.

- Gender differences: The positive effects of lower IGF-1 on longevity seem to be more pronounced in females in both human and animal studies.

- Extreme lows: Chronically low IGF-1 can be a sign of conditions like Laron Syndrome, which is associated with health problems.

Conclusion

While there is evidence that reducing high IGF-1 can increase longevity, a dangerously low level is also a health risk. The ideal IGF-1 level for longevity is likely not the lowest possible, but rather within a healthy, moderate range.