A reasonably good overview of the scientific momentum in biology of aging research…

The growing social and economic concern of an aging world population has catapulted aging-related research into the spotlight. Indeed, over the past decades, progress in medicine has powered a significant increase in life expectancy worldwide. Thus, more than 2 billion individuals are expected to be older than the age of 60 by 2050. (1) This demographic milepost will come with a major increase in age-related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer, which effectively double in incidence every 5 years passing the age of 60. (2) The relationship between aging and these diseases has triggered fundamental research into the aging mechanisms and approaches to attenuate its effect.

Aging is broadly defined as a gradual functional decline in the living organism’s intrinsic ability to defend, maintain, and repair itself in order to keep working efficiently and has attracted attention throughout the history of civilization. (3,4) The health and survival of an organism present a dynamic equilibrium between the processes of damage and repair, alteration, and maintenance, a conventional concept of which is homeostasis. This concept, recently replaced by homeodynamics, involves the constantly changing interrelations of body constituents while an overall equilibrium is maintained. (5) Thus, aging is characterized as a multidimensional process involving a gradual contraction of homeodynamic space. It affects many different aspects of life including physical health, cognitive functioning, emotional well-being, and social relationships. There is a consensus that aging is associated with two key aspects: (i) the progressive decline of numerous physiological processes, such as the body’s ability to accurately regulate homeostasis, and (ii) the enhanced risk of developing severe diseases such as cancer or cardiovascular disease. However, while aging is a major risk factor for many chronic diseases, it is important to recognize that aging and disease are not synonymous. Many older adults maintain good physical and mental health well into old age, and there is growing interest in promoting “successful aging” by focusing on factors that contribute to overall health and well-being. (6,7)

Researchers have distinguished between two categories of age: the chronological age based on the birthdate, and the biological age, which measures the true age at which the cells, tissues, and organs appear to be, based on biochemistry. (8) While it is impossible to alter the chronological age, there are ways to manage biological age. Since aging is influenced by multiple factors, including genetics, lifestyle aspects such as diet, exercise, and stress, environmental factors such as pollution and climate change, and social factors such as social support and socioeconomic status, interventions such as lifestyle adjustments, medical treatments, and social programs can help promote healthy aging and extend the lifespan. Understanding the complex interactions between these factors is essential for promoting healthy aging. (9)

Along with the whole organism, the functional capabilities of the brain gradually degrade upon aging, manifesting as declines in learning and memory, attention, decision-making capacity, sensory perception, and motor management. The aging brain exhibits significant indicative signs of impaired bioenergetics, weakened adaptive neuroplasticity and resilience, anomalous neuronal network activity, dysfunctional neuronal calcium homeostasis, accumulation of oxidatively modified molecules and organelles, and inflammation. (10−16)Reduced number and maturity of dendritic spines in aging organisms, along with alterations in synaptic transmission, may indicate abnormal neuronal plasticity directly related to impaired brain functions. (14) At worst, neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular diseases, which strongly damage the basic functions of the brain, may develop. Thus, age-associated alterations render the aging brain vulnerable to degenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, stroke, and various kinds of dementia. (17,18) While currently there is no cure for these age-related brain disorders, early detection by recognizing symptoms can help slow the progression of the disease.

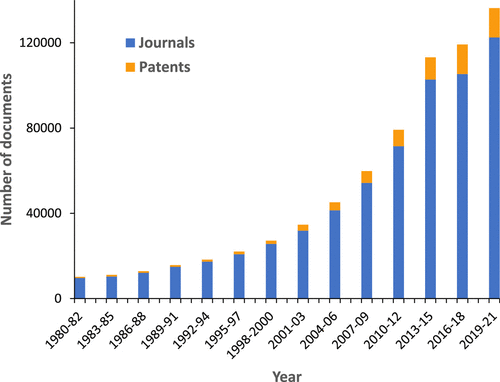

Figure 1. Yearly growth of the number of aging-related documents (journal articles and patents) in the CAS Content Collection.

Full, Open Access Paper: