Yes - I’ve had the rash spots before. They usually go away after a few days.

Sinclair is the worst. His MO of taking a supplement that is readily available and lobbying the FDA to make it a patented prescription drug for personal profit is truly slimy. His $720,000,000 fraud with Glaxo ends up costing us all money.

Matt Kaeberlein has given me no reason not to trust him so far.

Brad Stanfield seems to do a pretty good job reviewing the efficacy of supplements.

Rhonda Patrick makes too many far fetched, unsupported claims.

Peter Attia is hit and miss. His biases do not allow him to be objective enough for me, and he is making a fortune promoting AG1.

I am not aware of everyone, but it mostly gets worse from here.

What do you mean with this?

Sinclairs company based on Resveratrol was sold to Glaxo for $720m and Glaxo subsequently wrote it all off as completely worthless. I forget which year they did this but it is in their Annual Report & Accounts from several years ago.

(Sinclair himself trousered a double digit $ million amount as by then he was only a minority shareholder).

I can’t wait for your interview of VLMD. Her favorite cell is the macrophage. I know it’s too late but did you by chance get to ask her about beta cyclodextrin?

Yes… here is the info. I think calling it “fraud” is too strong a term (at least given what I’ve read). Most small molecule R&D efforts end in failure, and Glaxo is a sophisticated company that did its due diligence. Did Sinclair overstate the potential, did the earlier studies his lab do have problems… you can decide for yourself.

https://www.nature.com/articles/nbt0310-185

https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/sirtris-compounds-worthless-really

The science on Resveratrol was junk. Are we to assume Sinclair did not know this? Anyhow, he is not a friend of the longevity community when he lobbies to remove supplements from the market.

I’ll never forget kaeberlein saying that he (and others) tried and failed multiple times to replicate Sinclair’s research.

How many compounds was in Sirtris Pharmaceuticals?

Which supplement was removed from market?

I am not here to debate or do research for others that is available with a quick Google search. You are entitled to your own opinion in regards to Sinclair.

Sinclair created market demand for Resveratrol and MNM, then lobbied FDA to ban as supplements for monetary gain.

Well technically MNM was not removed from the market. He just wanted it to be sourced by companies that he had a financial interest in.

IMO: David Sinclair is more interested in fame and profit than science.

Which is very sad. Why can’t we ever get someone who cares about money and their own life?

I think most scientists in the aging field are pretty good in this regard, Sinclair is the outlier. If you look at Kaeberlein, Brian Kennedy and the NUS scientists, the Buck Institute scientists, etc. most of them are very focused on moving the science forward with science that can be duplicated by other labs, and in helping the broader populace.

Generally this group of researchers is quite good. Some are getting more involved in commercial efforts, but the good ones don’t over-hype the results of their studies and acknowledge the limitations of their research.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned NMN in 2022 from being sold as a dietary supplement.

Yes - see this story

FDA Bans NMN as a Dietary Supplement: Why and What Happened?

Healthnews has compiled the timeline of events leading up to and after the FDA banned NMN. We detailed the twists, turns, and unexpected roadblocks for consumers and companies hoping to market the anti-aging compound.

However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned NMN in 2022 from being sold as a dietary supplement after initially allowing one company to market it as a dietary supplement, sending shockwaves through the supplement industry and organizations that support natural health products.

There are many loopholes in this ruling.

There are still many ways to get NMN if you actually want some.

It is still being sold in the U.S. and can be imported from many countries like Japan.

“As of January 2024, the FDA has not enforced the ban on Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN) supplements in the U.S”

“As of January 2024, the FDA has ruled that nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) cannot be legally marketed as a dietary supplement”

Some are even ignoring the "supplement’ ruling.

"Lawsuits Against FDA’s NMN Ban Could Be Coming Soon

“Healthnews

https://healthnews.com › News

Has the FDA enforced the ban on NMN supplements? from healthnews.com

Dec 4, 2023 — The FDA had previously accepted NMN as a New Dietary Ingredient (NDI), which allowed supplement manufacturers to market it.

It is currently still being sold in the U.S.”

https://www.muscleandstrength.com/store/ff-nmn.html?___store=default

P.S. I am only beating this to death because I have already been to the gym and done my chores, so for the moment I have nothing better to do. ![]()

Well, I normally shop Amazon out of convenience, not that I like to support them, and they do not sell it anymore.

It’s OK, I have already read many of your posts and appreciate the knowledge and experience you share here.

Funny - It was David Sinclair who convinced me to try Rapamycin. I saw an interview with him where he was asked if he took it. His answer was something like “I tried it, but then I got a cold and I never get colds and this convinced me not to continue.” This seemed way to unscientific of an explanation from someone who is supposed to be a real scientist. I read this as Sinclair secretly does not want people to take Rapamycin. It must run counter to his business interests. So, then I sent an email to Dr Green and signed myself up for Rapamycin.

There was one more data point I should mention. I saw an interview with Brian Kennedy where he was asked about Rapamycin. He very uncomfortably answered that it was the most promising intervention at the time. It was clear that he had a reason not to promote Rapamycin but was not quite able to get himself to lie about it and discourage others from trying. We now know why he avoided the endorsement. He is peddling urolithin, which would be interesting were it not for the existence and easy availability of Rapamycin.

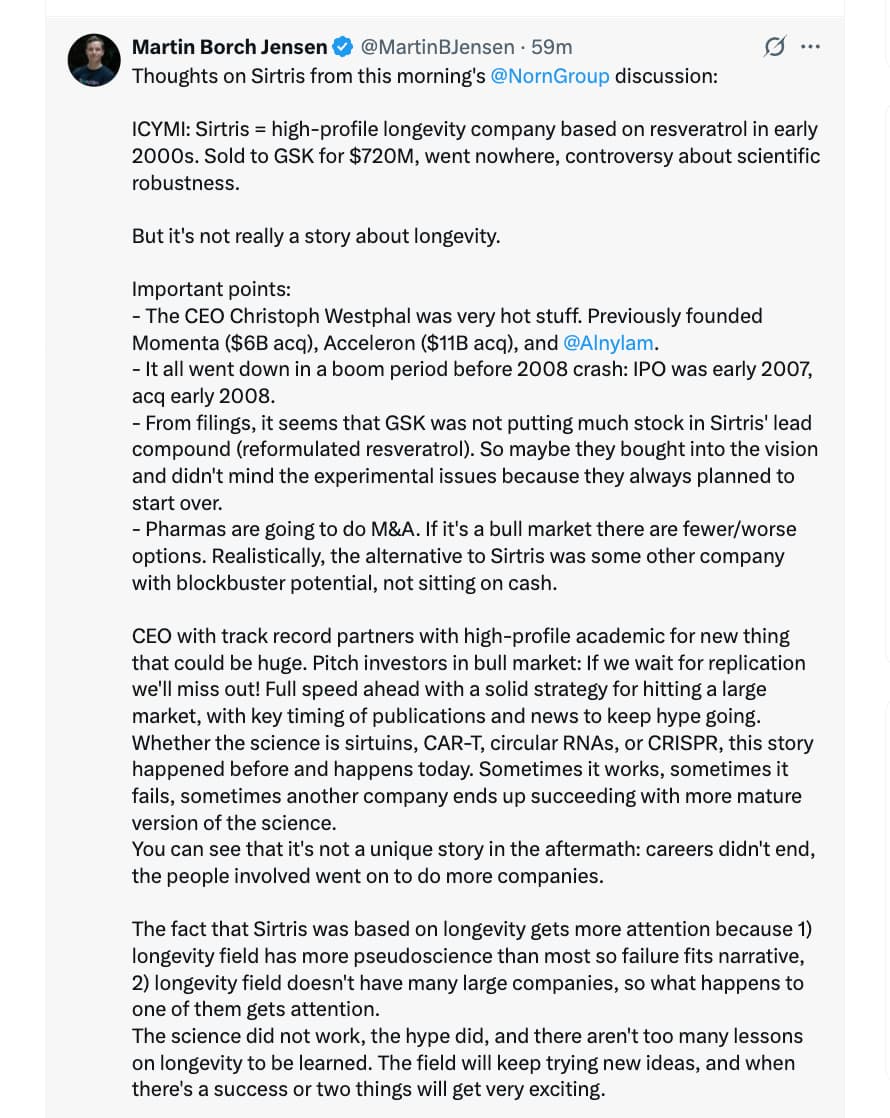

Some new analysis of the Sirtris failure, from today’s Age1 VC newsletter:

- Sirtris Pharmaceuticals

In April 2008, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) agreed to acquire David Sinclair’s spinout, Sirtris Pharmaceuticals, for ~$720M cash to access the company’s lead sirtuin asset (SRT501) for metabolic and degenerative diseases. Notably, GSK paid this price at an 84% premium —that is, at a price 84% greater than the company’s pre-acquisition valuation. Critics commented that the GSK acquisition was naïve, as the company had only a single compound in trials (SRT2104 in Phase 1b for ulcerative colitis), and there was insufficient evidence for human efficacy.

The mechanistic premise became even more controversial after Pfizer and other groups (Amgen, University of Washington) increasingly failed to replicate Sincair’s data. In May 2010, GSK suspended a Phase 2a trial of high-dose micronised SRT501 in advanced multiple myeloma after several patients developed nephropathies; as GSK told FierceBiotech, the compound “may only offer minimal efficacy while having a potential to indirectly exacerbate a renal complication common in this patient population.” Finally, in late November 2010, GSK ceased all programs related to SRT501, but stated that they remained interested in developing SRT2104 and SRT2379, biosimilars to SRT501 with “more favorable properties.” By 2013, GSK shut down Sirtris’s Cambridge lab, and the company was effectively dissolved into GSK’s R&D.

Unfortunately, a 2014 trial found that a 28 day course of SRT2104 had no protective effect in type II diabetes patients, nor ulcerative colitis in a 2016 trial, and SRT2379 was unable to modulate the inflammatory response of healthy male subjects after exposure to lipopolysaccharide (however, SRT2104 did prove successful in stimulating anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant responses in a later trial). In any case, no Sirtris compounds advanced quickly enough within GSK, and the pharma company seemingly let go of the sirtuin platform after 2015. While many other groups in the years following have continued exploring new indications for compounds in the SIRT-1 activator class, a sirtuin activator has yet to be approved and deployed into the market more than 25 years after Sincair’s initial yeast aging discovery.

What went wrong?

The Sirtis story represents both a lesson to founders and investors. Paying an 84% premium for a platform with unvalidated data put GSK in a problematic position when third‑party labs contradicted Sirtris’s SIRT1 activation data; ultimately, GSK should have reproduced the company’s data independently before writing a nine‑figure check. On the other hand, Sirtris should have controlled for assay artifacts. Pfizer’s study found that Sinclair’s activator compounds bound to the SIRT1-fluorescent peptide complex, but when they removed the fluorogenic group, calorimetry confirmed that the compound only bound to the artificial peptide-enzyme complex and not SIRT1. GSK may have been able to get ahead of the criticism by imposing a more stringent post‑merger governance model; however, the pharma seemingly granted Sirtris full autonomy in Cambridge.

Takeaways

The grim baseline is well known. In 2015, it was estimated that only one in every 5,000 compounds (0.02%) discovered and tested preclinically would get approved; of the drugs started in clinical trials in human participants, only 10% would secure FDA approval. In a later analysis of the period between 2014 and 2023, Citeline estimated the average likelihood of approval (LOA) for a new Phase I drug to be 6.7%, an all-time low. According to Citeline, the leading cause of failure remains the “Phase II hurdle,” with a 28% completion rate compared to Phase I (47%) and Phase III (55%).

Yet molecules are only half the story; many companies fail for reasons that have little to do with science. For some fledgling companies, lack of access to supply chains, industrial-scale CMC expertise, and regulatory teams sink the startup rather than drug efficacy; it is mainly for this reason that securing a corporate partner can be the decisive bridge to carry a program through trials. In a study in Nature Biotechnology , analysts from two Dutch venture firms mined GlobalData’s Pharma database for every large‑pharma/biotech startup deal made between 2004 and 2019. They then asked whether prior pharma ties predicted startup “success,” defined as going public, being acquired, or securing at least one drug approval during that window. Startups with a large‑pharma investor to guide operations nearly doubled their median odds of success (37% vs 18%) and achieved bigger outcomes—market cap rose from $138M to $332M, and median acquisition value from $136M to $377M.

According to Fierce Biotech, venture failures peaked in 2023 with 27 closures, which dropped to 22 in 2024; sources have yet to compile data on how well biotechs fared in 2025, although age1’s analysis tallied 15 as of August 14th. However, the same reasons for failure arise year after year. In 2022, BioSpace interviewed several CEOs and VCs on this topic: many mentioned overlapping themes: poor capital management, inadequate flexibility, and miscommunication across hiring, development, management, and more. It’s worth stating clearly that most biotechs do not fail because their founders are inept or their science is faulty. In fact, the opposite is true—the companies profiled in this piece were founded by credible, well-intentioned teams and built around plausible mechanisms. Still, building in biotech, for the reasons outlined above and more, is brutally hard. More specifically, failure is far and beyond the statistical default. Some of these companies did not fail from one single decision, but a series of missed pivots, unhedged assumptions, and cracks that gradually widened over time, whose consequences were only visible in hindsight.

Ultimately, our analysis of biotech failures reveals that clinical readouts are rarely the only cause of shutdown. While disappointing clinical trial outcomes are the most ubiquitous catalysts for a biotech’s downfall, what separates those who can bounce back from those who can’t is behind-the-scenes operations. Importantly, operational robustness can sometimes overcome scientific setbacks (e.g. Exelixis’s strategic reprioritization post-COMET-1 trial failure). Conversely, operational blunders can sink even scientifically promising ventures (e.g. Dendreon’s miscalculation of demand, COGS, and CMC for prostate cancer treatment, Provenge).

One factor that separates survivors from casualties is whether management aligns trial endpoints with true patient benefit. Allakos drove eosinophil counts down, yet ignored tepid symptom data; its pivotal ENIGMA‑2 study missed both co‑primary clinical endpoints and imploded a multi‑billion‑dollar valuation. While biomarker wins are necessary, they are never sufficient. Clinical rigidity (likely a byproduct of belief in the sunk-cost fallacy) also remains a major driver of biotech failures: Argos pressed on with their renal‑cell vaccine after a data‑monitoring committee declared futility. An extra year of spending only confirmed the verdict and left little capital for a pivot. Those with a long-term vision, including plans for expanding into new indications or developing additional assets beyond their lead candidate, will consistently outperform startups focused solely on short-term goals.

Balance sheet architecture is another tripwire. Walking Fish relied on a single late‑stage investor and spent against money that was not yet in its pockets; when that backer walked, the Fish couldn’t: fixed costs outpaced runway, and the company closed despite a recent $73 million raise. Athersys, by contrast, conducted a mass layoff to cut costs after a stroke trial failed, breaching the fine print on a $100 million equity financial agreement. Contingency capital is an inevitable and essential source of funds, but can never be relied upon to the extent that a loss of such funds would bring down the company.

Overdependence on single partnerships also remains a source of caution. While SQZ publicized a “$1 billion” Roche alliance, only $94 million was ever wired. When Roche declined its option, it led to liquidation. Investor trust is equally essential. Zafgen’s decision to withdraw from an investor conference after a trial death and stay silent for days was significantly damaging; the stock had already lost half its value by the time management confirmed the fatal thrombotic events. Even if transparency can’t revive bad data, opacity compounds the damage.

Another recurring error is letting valuation outpace validation. GSK paid an 84% premium to acquire Sirtris on the strength of unreplicated assays; subsequent independent work showed the lead compound bound to an artificial fluorescent substrate, not to SIRT1 itself. By the time Sinclair could publish a rebuttal, it was too late—the program was abandoned within five years. Ultimately, a late‑stage independent diligence repeat can turn out to be cheaper than a nine‑figure investment.

Across these cases emerge consistent patterns: financial mismanagement, communication failure, over-reliance on single partners, clinical rigidity, and more. While addressing these factors can’t guarantee success, they do significantly influence whether a missed primary endpoint becomes a temporary setback or an obituary. Stay tuned for Part II: next week, age1 will publish a systematic review of 64 publicly disclosed biotech shutdowns (2023–2025), organized into six root-cause clusters, alongside an operator checklist we believe every founder should use as they build.