I talked with Adam Salmon a month ago, and the paper is still a work in progress. He didn’t give a date of expected publishing, but its in process.

The study masterjohn refers was 14 months. Marmosets last 12 years

In my admittedly quick search of literature I couldn’t find negative impacts of Rapamycin on the heart.

I have never heard of heart scarring either. However a simple Chat GPT search produced the following:

-

Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, is an immunosuppressive drug that can have serious side effects, including pulmonary complications. Overdosing on rapamycin may increase the risk of lung-related issues such as interstitial pneumonitis (IP), which can lead to lung scarring.

-

Rapamycin’s effects on the heart are complex. While it is being studied for its potential to improve cardiac function and reduce inflammation, overdosing or inappropriate use could lead to adverse effects, including potential scarring or damage to heart tissue. Excessive inhibition of mTOR, the pathway targeted by rapamycin, might disrupt cellular repair processes, which could theoretically contribute to scarring.

In both examples, it’s OVERDOSING that creates scarring.

Aah, now if only we knew the exact dose where it becomes “overdosing” (probably individually variable), we’d be in clover.

Meanwhile we have desertshores who saw no sides at super high doses and others who couldn’t take 1mg a week.

For the record, I’m a 73 year old Rapa user (6mg ~every other week). I want to believe it’s having a beneficial effect and may partially contribute to my excellent health and vitality. That said, (with the help of Gemini AI), let’s review the consistency of Chris Masterjohn’s article with other research and identify potential flaws or counterarguments.

Consistency with Other Research:

- Lifespan Extension in Model Organisms: It’s highly consistent with research that rapamycin robustly extends lifespan in various model organisms, particularly mice. This is a foundational finding in geroscience.

- Mechanism (mTOR Inhibition): It’s consistent that rapamycin works primarily by inhibiting mTOR (specifically mTORC1), a key nutrient-sensing pathway involved in growth, proliferation, and autophagy. The idea that inhibiting mTOR mimics aspects of caloric restriction or fasting is also widely discussed.

- Reported Side Effects: The specific side effects Masterjohn highlights (impaired glucose metabolism/insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, testicular atrophy/lower testosterone, cataracts in mice, mouth sores/stomatitis, impaired wound healing, potential immune modulation) are consistent with side effects reported in both animal studies and human clinical use (especially in transplant patients receiving higher, continuous doses).

- Intermittent Dosing Strategy: It’s consistent that intermittent dosing (e.g., weekly) is being actively researched and used precisely to mitigate the side effects seen with chronic dosing, while potentially preserving some or all of the benefits. His points about intermittent dosing not fully resolving all issues or potentially having sex-specific effects on lifespan are also reflected in specific studies (though the overall picture is still evolving).

- Concerns about Translatability and Optimal Dosing: The concern that findings in mice (especially regarding dose-response and specific side effects) may not perfectly translate to humans, and that the optimal human dose/schedule for longevity is unknown, is consistent with the general scientific consensus. There’s active debate and research on this.

- Importance of Nutrient Cycling: The biological principle that cycling between periods of nutrient scarcity (catabolism, autophagy) and nutrient abundance (anabolism, rebuilding) is beneficial for health is consistent with broader metabolic research. Many researchers agree perpetual inhibition of growth pathways might be detrimental.

Potential Flaws, Biases, or Counterarguments:

- Strong Negative Framing & Tone: The title (“Worst Longevity Idea Ever Conceived”) and strong language (“shuddering,” “trashed testosterone”) signal a very firm negative stance from the outset. While based on data, this framing might lead to a less balanced interpretation, potentially overemphasizing negatives and downplaying potential positives or mitigation strategies.

- Emphasis on High-Dose/Chronic/Disease Context Data: Masterjohn heavily cites side effects from mouse studies often using relatively high chronic doses needed to achieve maximum lifespan extension, and human data primarily from transplant recipients or patients with specific diseases (like LAM) who often receive higher daily doses and have underlying health issues/confounding medications. While relevant, this data may not fully represent the risk profile of the lower, intermittent doses (e.g., 5-7 mg once weekly) commonly explored for anti-aging in relatively healthy individuals. The article acknowledges dose differences but often draws strong conclusions from the higher-dose contexts.

- Interpretation of Dose Comparison: While correctly noting that typical human anti-aging doses are often lower than effective mouse lifespan-extending doses (when adjusted), concluding they are therefore ineffective or only cause harm is an interpretation. The dose-response curve for longevity and healthspan benefits vs. risks in humans is simply not established. Lower doses might yield different benefit/risk profiles than higher doses.

- Downplaying Intermittent Dosing Potential: While acknowledging intermittent dosing studies, the article emphasizes their limitations rather than their potential successes in mitigating side effects. The research landscape here is complex and ongoing, with some studies showing significant reduction in side effects with intermittent schedules.

- Selectivity in Evidence: Like any viewpoint article, there might be selectivity in which studies are highlighted. For example, it focuses less on studies showing potential benefits of rapamycin or its analogs (rapalogs) for specific age-related conditions or improved immune function (e.g., response to vaccines) in older adults even at lower doses.

- Extrapolation Certainty: While acknowledging the need for caution, the article makes strong negative assertions about human effects based heavily on mouse data (e.g., projecting mouse testicular atrophy directly onto human testosterone levels at anti-aging doses).

- Promotion of Alternatives: The conclusion transitions into promoting the author’s own specific protocols and products. While authors often suggest alternatives, explicitly linking to paid protocols can be seen as a potential conflict of interest or bias.

Conclusion:

The article raises valid and important concerns about rapamycin, grounding them in published research regarding significant side effects observed in animal models and certain human contexts. The facts cited about specific adverse outcomes are generally consistent with the literature.

However, the article presents a particularly critical and arguably one-sided perspective. It heavily emphasizes the negatives, draws strong conclusions based often on high-dose or non-longevity contexts, and may downplay the potential for mitigation strategies like optimized intermittent dosing. The actual risk-benefit profile of low-dose, intermittent rapamycin for human aging is still an area of active research and considerable debate, with proponents believing the benefits can outweigh the risks with careful management, while critics like Masterjohn remain highly skeptical. His article represents a strong voice on the skeptical end of that spectrum.

It shows that “dosing” is pretty much individual. If and when you get your first side effect, it’s a sign that you overdosed and need to cut back instead of tolerating mouth ulcers.

I find that dosing at 4mg + GFJ per week has the best effect on my arthritis. No pain even in the colder months. I’m tempted to go 5mg or 6mg but for now no reason. My 36 hour blood work is about 12ng/mL. Residual of about 1.7ng/mL on day 7.

You guys are way too reliant on these LLM models, and you should be more careful. They are very easily “persuaded” by the way you ask the question, and they still tend to spout nonsense - usually telling you what you want to hear.

The reference Masterjohn gives for the cardiac scarring is this one: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212877824000334

The study itself is great, and contains lots of information - both positive, neutral and negative. There is a brief mention of cardiac fibrosis (not “scarring”, just to be clear) in the text. The data is in supplemental figure 7, and there is some increase in “mild” fibrosis in the male mice, which looks like it was in 5% of old mice, and around 25% of old mice with Rapa. There was no difference in any of the female mice. So, is it interesting there male mice had fibrosis? Sure. Does it mean Rapa ‘scars your heart’ and shouldn’t be taken? That’s a very different question.

Luckily, the same paper actually investigated cardiac parameters and physical performance. They show that Rapa improved the motor endurance, allowed the male mice to run on the rotarod (like a moving balance beam) for longer. Rapa also improved a bunch of cardiac electrophysiological parameters, and it reduced ventricular hypertrophy. Together, it looks like functionally the mice were overall better off, plus they lived longer. So whether the fibrosis is truly a negative is not really known.

Writing “it scars your heart” is either very lazy writing, or a deliberate attempt to exaggerate negative effects.

In terms of lifespan data, this study is less convincing that the ITP data. And from the ITP, we already knew there’s a difference between male and female. However, what I learned from this study is that there is actually a huge difference between the responses of male and female mice, at organ-specific levels. We have these seemingly conflicting findings where biomarkers and actual function are divergent. For me, a study like this reminds me that we really don’t understand what’s going on here, and most of these observations can’t be explained. We also don’t know how much is just an anomaly of mouse studies, and we urgently need those macaque and dog trials to give us more useful data.

I wonder if the user’s experience here is another example of the function divergence

I largely agree with this article based on my experience using Rapamycin. I stopped using it after it made me anemic. I now will only use things that have shown some benefit in human trials. The TRIIM Trial protocol gave me good results.

Exactly… I take 1 mg every other day and that works great for me. Have tried so many other protocols (weekly, biweekly) with horrible adverse effects.

How did it make you anemic? What is the reason? Do you have a condition?

I have seen this effect while taking rapamycin in high doses. That is one reason I dialed back my dosage.

This is a well-known effect. I think we have discussed it previously.

“Rapamycin (sirolimus) has been linked to microcytic anemia, characterized by small red blood cells (low mean corpuscular volume, MCV) and reduced hemoglobin levels”

“Bone Marrow Suppression: Rapamycin inhibits the mTOR pathway, which regulates cell proliferation. While this can suppress pathological T-cell activity (beneficial in autoimmune anemia), it may also reduce red blood cell production in healthy individuals, contributing to mild anemia”

I think the lower MCV is a real issue. People like it because the Levine formula likes it. However, it is not necessarily good.

High-dose rapamycin reduced my hemoglobin levels more than MCV.

Interesting, when I had 20mg every week with GFJ before, I know my level was over 40ng/mL… but I never felt anemic. Perhaps that is the least of my issue.

Agreed. I think a large MCV is fairly well accepted as “bad”, but I am not confident there is a specific advantage of having a low MCV. Assuming there’s no iron deficiency or thalassemia, the usual cause (from what I remember of my haematology training) is related to the amount of cell division in the bone marrow. Maybe that’s where Rapamycin is affecting things.

So personally I’d like something at the low end of normal, and of course making sure that the total RBC count and HB are normal.

Did you ever have a blood test? I was quite surprised to learn that a lot of people never feel anaemic. When I worked in the hospital haematology and transfusion department, we would get ‘walk-in’ patients who seemed just fine, and you test them and their HB is like 7 or 8 g/dl. I always thought that with numbers like that you’d be keeling over, feeling horrible, but apparently not.

mTOR is a nutrient sensor. If we want to leverage it toward longevity, it should be with nutrition.

However, as I covered in Does Molybdenum Lengthen Lifespan?, glycine is an mTOR activator, yet lengthens lifespan.

Methionine restriction lengthens lifespan, but so does increasing molybdenum cofactor synthesis.

The intersection of methionine, glycine, and molybdenum cofactor synthesis is all on sulfur. Most likely, minimizing excessive hydrogen sulfide, sulfite, and S-sulfocysteine is the path to longevity that ties these all together, so if I had to make a bet, I would bet on my Sulfur Protocol outperforming rapamycin for boosting both healthspan and lifespan. You can get it here:

To the extent glycine lengthens lifespan beyond its buffering of sulfur catabolism, this argues for using my glycine protocol:

Using glycine to lengthen lifespan and boost healthspan likely requires minimizing its generation of oxalate. And for that, there is my oxalate protocol:

Lots of self-promotion, “should”/“I would bet” with no good evidence, and just overly speculative and mechanistic in general. Sorry, but if someone isn’t actively producing research in this field, I’m not going to take them seriously, granting a few exceptions for the MDs that really know their shit.

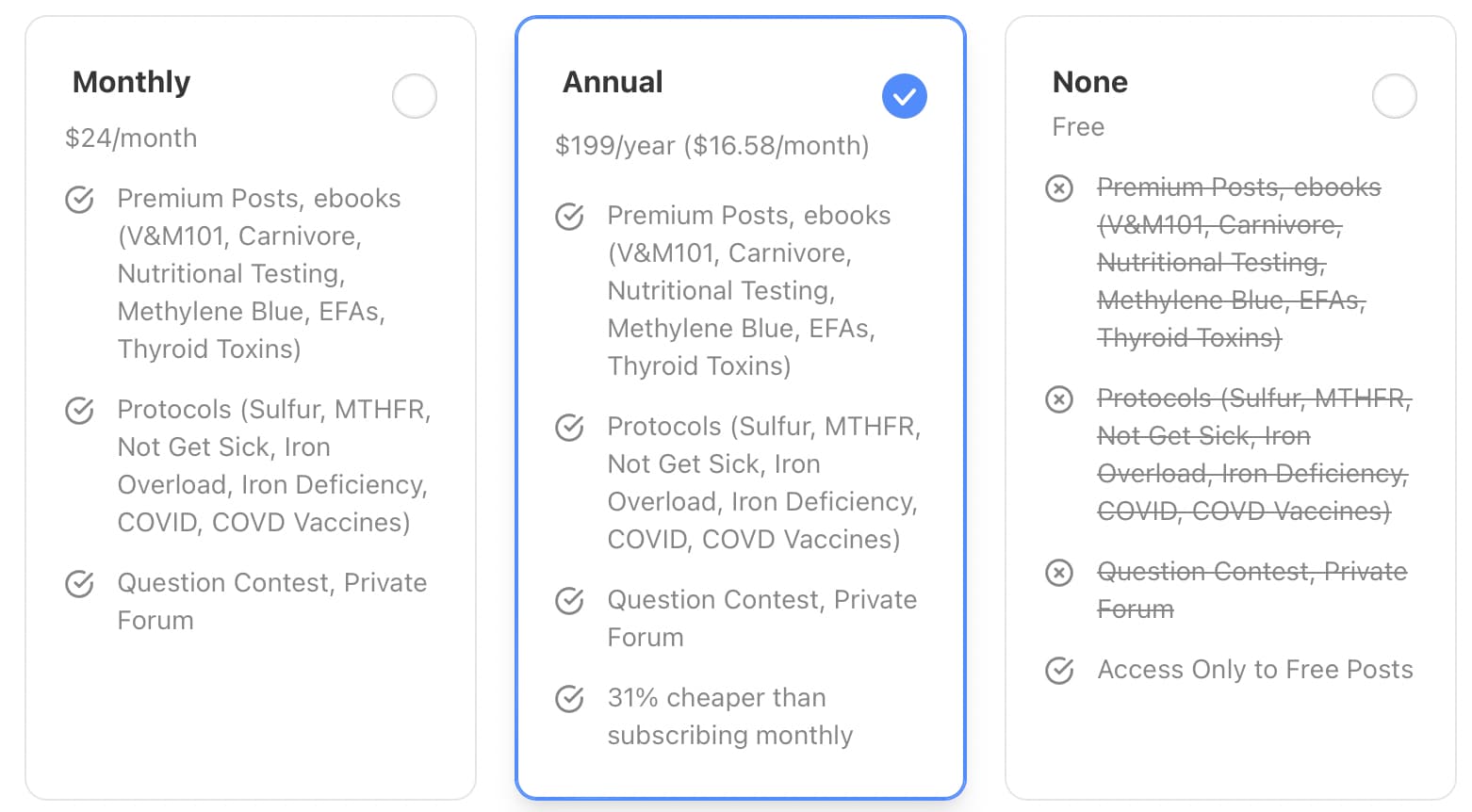

On the bright side, most of his nonsense is hidden behind a paywall.

I am 70 years old and I am in probably the best physical shape of my life. I work at it by exercising 6 days awek, eating Keto, intermittent fasting, and now for the last two years taking 6mg of Rapa once a week with occasional breaks. So far, so good.

I remember a while back one of the bit’s of informationon on Rapa I read that helped me make my dosing decision, was a chart showing the dosing regime of 10 of some of the most high profile advocates of the regime. I remember Dr. Attia and Dr. Kaeberlein and many more.

It would be interesting to see a follow up on that group to see if anything has changed.