I think the largely unexamined independent variable, likely embedded in a more complex relationship is certain kinds of persistent inflammation.

For those of you trying to lower Lp(a), this is a very interesting video. Nick has a genetically high Lp(a) level.

Why Vitamin C is the Most Underrated Nutrient for Heart Health

Summary ChatGPT 5 (Short Summary)

![]() Vitamin C is abundant in fruits, vegetables, and multivitamins, but its role in heart health is underrated.

Vitamin C is abundant in fruits, vegetables, and multivitamins, but its role in heart health is underrated.

![]() LP(a) (“evil twin” of LDL) promotes clotting and atherosclerosis; new drugs target it, but high-dose vitamin C may help.

LP(a) (“evil twin” of LDL) promotes clotting and atherosclerosis; new drugs target it, but high-dose vitamin C may help.

![]() Linus Pauling & Dr. Rath hypothesized LP(a) evolved as a substitute for vitamin C in humans who lost the ability to synthesize it.

Linus Pauling & Dr. Rath hypothesized LP(a) evolved as a substitute for vitamin C in humans who lost the ability to synthesize it.

![]() Animal studies: guinea pigs deprived of vitamin C rapidly developed heart disease with LP(a) buildup; supplementation reversed this.

Animal studies: guinea pigs deprived of vitamin C rapidly developed heart disease with LP(a) buildup; supplementation reversed this.

![]() Human epidemiology: mixed results, but some studies show vitamin C intake linked to lower heart disease risk.

Human epidemiology: mixed results, but some studies show vitamin C intake linked to lower heart disease risk.

![]() Clinical trials: vitamin C improved blood vessel function, slowed restenosis after angioplasty, reduced oxidized LDL, and slowed atherosclerosis progression.

Clinical trials: vitamin C improved blood vessel function, slowed restenosis after angioplasty, reduced oxidized LDL, and slowed atherosclerosis progression.

![]() Mechanisms: (1) Diffuses LP(a) effects, (2) Acts as antioxidant lowering oxidized LDL, (3) Supports nitric oxide production for vessel health.

Mechanisms: (1) Diffuses LP(a) effects, (2) Acts as antioxidant lowering oxidized LDL, (3) Supports nitric oxide production for vessel health.

![]() Individual responses vary—those with high LP(a), oxidative stress, or poor vessel function may benefit most.

Individual responses vary—those with high LP(a), oxidative stress, or poor vessel function may benefit most.

![]() Dosing: RDA (75–90 mg) is for deficiency prevention, not optimization. Suggested range: 250–2000 mg/day depending on tolerance.

Dosing: RDA (75–90 mg) is for deficiency prevention, not optimization. Suggested range: 250–2000 mg/day depending on tolerance.

![]() Top food sources ranked by vitamin C per carb content; a “vitamin C bang for your sugar buck” approach.

Top food sources ranked by vitamin C per carb content; a “vitamin C bang for your sugar buck” approach.

![]() Vitamin C +

Vitamin C + ![]() Lysine = “Batman & Robin” duo for heart health—vitamin C strengthens collagen (reducing LP(a) stickiness) while lysine acts as a decoy to block LP(a) binding.

Lysine = “Batman & Robin” duo for heart health—vitamin C strengthens collagen (reducing LP(a) stickiness) while lysine acts as a decoy to block LP(a) binding.

![]() Protocol: 1 g/day vitamin C (split doses) + 2 g/day lysine may reduce LP(a) stickiness, lower oxidized LDL, and improve nitric oxide.

Protocol: 1 g/day vitamin C (split doses) + 2 g/day lysine may reduce LP(a) stickiness, lower oxidized LDL, and improve nitric oxide.

![]() Suggested tracking: LP(a), vitamin C levels, oxidized LDL, IL-6 (inflammation marker), before and after supplementation.

Suggested tracking: LP(a), vitamin C levels, oxidized LDL, IL-6 (inflammation marker), before and after supplementation.

![]() Reward: a simple, inexpensive protocol shared openly to help diffuse LP(a) risk and improve heart health.

Reward: a simple, inexpensive protocol shared openly to help diffuse LP(a) risk and improve heart health.

CHAPTERS

0:00 – Vitamin C: The Most Underrated Heart Health Nutrient

1:02 – Understanding Lp(a): A Key Player in Cardiovascular Health

1:58 – Roadmap to this Video: 8 Key Insights on Vitamin C and Heart Health

3:39 – Chapter 1. Vitamin C and Lp(a)

6:51 – Chapter 2: Vitamin C and Heart Disease

11:44 – Chapter 3: Vitamin C and oxLDL

13:07 – Chapter 4: Vitamin C and Nitric Oxide

14:25 – Chapter 5: Mechanistic Summary

15:35 – Chapter 6: Vitamin C Dosing

17:08 – Chapter 7: Vitamin C and Lysine

21:26 – Chapter 8: Puzzling Together the Protocol

24:46 – Call to Action: Help me Make Metabolic Health Mainstream

“https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.87.16.6204”

https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.87.23.9388

“Vitamin C and Heart Health: A Review Based on Findings from Epidemiologic Studies - PMC”

“https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.CIR.99.25.3234”

“https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.cir.0000050626.25057.51”

I used to take a lot of Vit C, a few grams a day. Chris Masterjohn spent maybe 3 articles talking about vitamin C and he thinks you should take very little. So I quit the synthetic stuff and went with the acerola cherry extract which is a pain to take. Then I saw a couple things that said to not take vitamin C with berberine, which I have twice a day. That leaves cherry extract at noon. I always forget and eventually ran out. So no more Vit C for the last few months. Now this. I really like Nick and I think he’s right. He’s only asking for 500 twice a day. I’ll order more and have a gram at noon.

Just a thought. Alternating days of 2 different statins (Rosuv 5mg and Atorv10mg) brought my LDL from 4.3 when only on Rosuv or only on Atorv (canadian units) to 1.2 (ideal is any thing below 1.8). Cardiologist had never tried this and now is curious why this would work. I was trying to avoid the side effects of each (which were different for each med).

That’s interesting, because my cardiologist at UCLA strongly discouraged taking two statins concurrently. I was on atorvastatin at the time, and my idea was to add rosuvastatin because it’s hydrophilic while atorvastatin is lipophilic, so I thought “best of both worlds”. Before I even finished my statement, he already knew where I was going, and stopped me - saying that this is the most common idea his patients have for treatment resistant lipids, and it’s a bad idea. I was rather taken aback and didn’t manage to press him too hard on the “why” it’s bad, but he mentioned something about the liver. Anyhow I was rather confused by the whole thing because when I thought of that idea, I of course immediately googled it and found nothing much, no real mentions or studies about mixing statins, so it was all rather disconcerting. I decided not to go against my cardiologist’s advice and I never revisited the idea.

What you are doing is slightly different insofar as you’re taking it one at a time, but my understanding is that it takes some time to fully clear the statin out of the body (about three days), so you still have some overlap. But you are getting good results, without apparent side effects, so that counts for something.

I don’t know what to think about this. Originally, contemplating the mechanisms of action of statins I didn’t see any reason why there should be a problem combining them, but you have to be super careful making decisions about taking a drug based on mechanistic speculations - add to that my cardiologist strong warning and paucity of any studies, and it made me back off. But what do I know, your mileage may vary.

my LDL dropped in 3 weeks and I always have liver, renal, and cbc profiles checked and there was no other effect. As well, I was on a low dose of each.

It’s an old paper but what do people here think about it?

Impact of Statins on Cardiovascular Outcomes Following Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring 2019

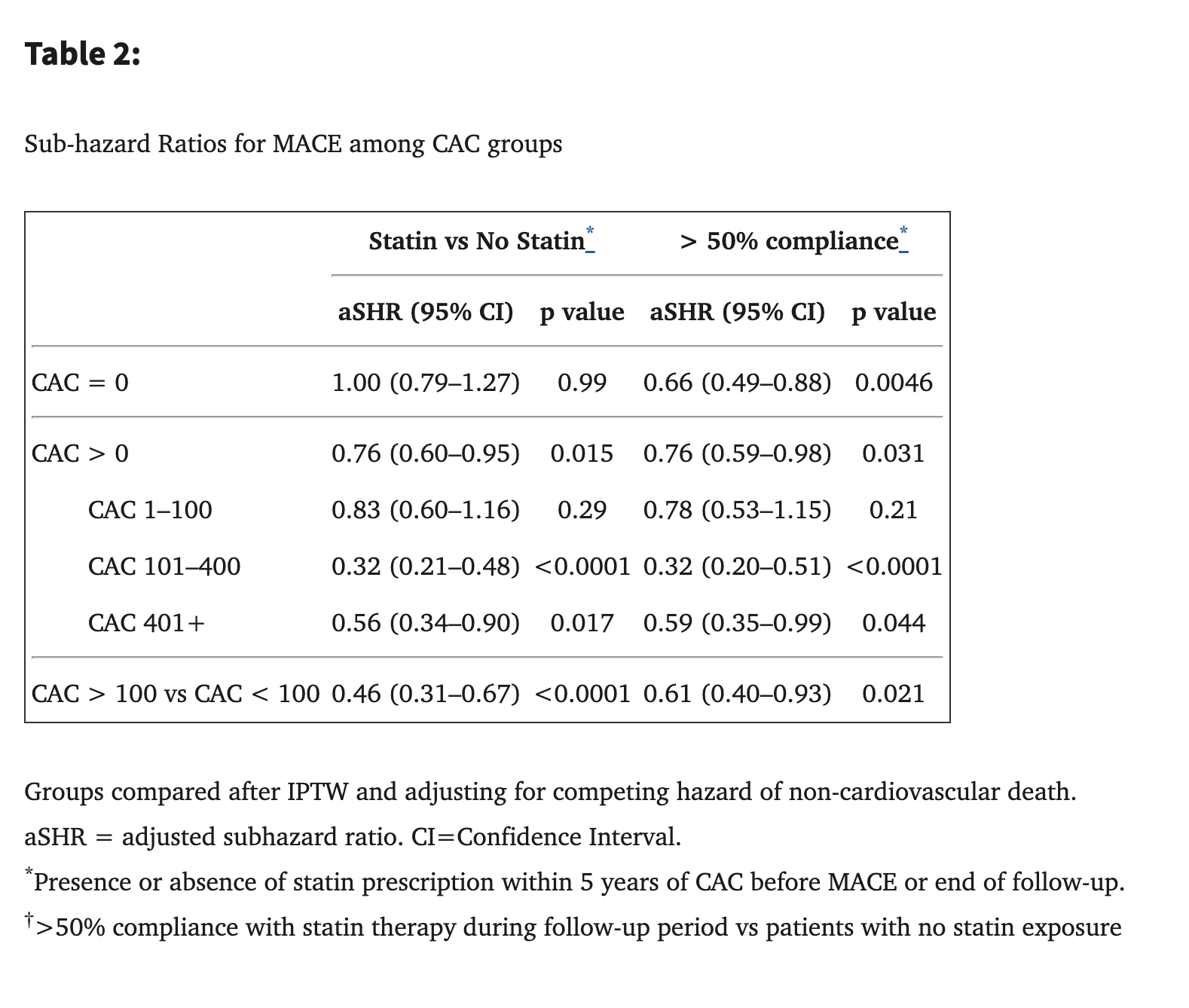

13,644 patients (mean age 50 years; 71% men) were followed for a median of 9.4 years. Comparing patients with and without statin exposure, statin therapy was associated with reduced risk of MACE in patients with CAC (adjusted subhazard ratio [aSHR] 0.76, 95% CI 0.60–0.95, p=0.015) but not in patients without CAC (aSHR 1.00, 95% CI 0.79–1.27, p=0.99). The effect of statin use on MACE was significantly related to the severity of CAC (p <0.0001 for interaction), with the NNT to prevent one initial MACE outcome over 10 years ranging from 100 (CAC 1–100) to 12 (CAC >100).

If 9 years is not enough to see benefits in people with CAC = 0, then what’s the point of taking statins for prevention? The only thing I could imagine is: “You don’t want to do a CAC CT scan yearly due to radiation so you might miss exactly when your CAC goes above 0 and treatment should start and then you cannot reverse it so better to start lipid-lowering therapy now”. Is there a better line of reasoning than this?

I think it would matter which statin. Those which concentrate on the liver are probably better.

Hey, that’s an interesting study which I wasn’t familiar with, thanks for sharing.

My immediate thoughts:

-

We need to point out that the statin group did have a significant reduction in MACE. So the CAC is more like bonus information and not really a deciding factor in whether to treat. I would personally just go by LDL-C/ApoB.

-

If you look at Table 2, if I’m reading correctly, once they adjusted for compliance (I.e. people actually taking the statin, not just being prescribed it), the CAC = 0 group now did have a significant reduction in MACE: aSHR 0.66, (95% CL 0.49–0.88), P = 0.0046.

-

To explain the rationale, as you know, CAC is a lagging marker, which means you’ve already made plaque and it’s been there long enough to calcify before you can detect it. That can take 2 years if you have rapid calcification, or up to 10 years if you have slower calcification. So waiting for CAC > 0 means you’ve potentially had years of soft plaque buildup.

-

The mean age in the study population is only 50. So to have an MI or any MACE within 9 years of that means you were in fairly poor health to begin with. I think all of us are looking on longer trajectories than this.

I’m always shocked at the massive % of people who don’t take the medications, lol. I assume that the readership of this forum is extremely different to that study population, and we will have extremely high compliance and

Excellent point that settles the debate I think:

Comparing patients with and without compliant statin exposure (>50%) after IPTW, compliant statin therapy was associated with reduced risk of MACE in all patients (aSHR 0.76, 95% CI 0.63–0.91) without a significant interaction with presence of CAC (p=0.42 for interaction). After IPTW, the groups were appropriately balanced on all variables (Online Table 8).

You choose these 2 statins because 1 is hydrophilic and the other is lipophilic?

Prevention of MACE is of course important and debatable, I just want to quickly mention, that obviously MACE prevention is not the only reason people take statins. I have had a CAC score of zero two years ago (at age 65), but I do have garbage lipids. I however take statins (currently pitavastatin 4mg/day) for their pleiotropic benefits. If you look at the literature, the non-MACE related benefits are very widespread, and I would take a statin even if my lipids were perfect and I had no MACE risk. Frankly I’m not particularly worried about MACE in my case, but I’m persuaded that elevated ApoB is harmful in many contexts apart from CV, including cancer. Statins, are wonder drugs, though they can have side effects, and you should make sure you are a good candidate based on your unique situation, and if yes, then pick your statin and dose carefully. Based on this study I would not stop taking my statin. YMMV.

Not really, although I suspect the side effect profile is different between Rosuv/Atorv because of the differences in lipophilic-hydrophilic. With Rosuv I experienced brainfog and caffeine sensitivity. But with Atorv I experienced glute muscle cramps.

As someone who is also intolerant of statins, I would try using a combination of GLP1, ezetimibe, bempedoic acid and omega 3 EPA instead. My recent LDL-C and triglyceride values were insanely good with that combination.

I’d trust you as a source more than I’d trust a lot of the reddit sources that the LLMs seem to use.

2025 Meta-Analysis: RCTs do not Support Restricting Saturated Fat for reducing cardiovascular events.

There is more Nuance involved.

2025 meta-analysis of 9 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving over 13,000 participants, concluding that restricting saturated fat intake does not reduce cardiovascular disease risk, mortality, or events like heart attacks.

Overview of the underlying 9 RCTs (used ChatGPT here)

‘experimental’ groups (groups that reduced % of SFA)

6 increased intake of Linoleic acid (Omega 6) PUFA.

1 increased intake of Linoleic acid + Oleic acid (Olive oil)

2 only decreased saturated fat without an accompanying increase unsaturated fatty acid.

‘control’ groups (groups that maintained or increased SFA)

1 relied on coconut oil, the others used animal fats.

So in summary: Its not looking at ‘SFA vs MUFA’, or ‘SFA vs Omega 3 PUFA’

It’s looking at replacing SFA with Omega 6 PUFA, or (in the case of 2 of the studies) just reducing SFA %.

The Study:

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jmaj/8/2/8_395/_pdf/-char/en

Editorial on the study:

There’s a good video on it here:

There was a reduction, it just wasn’t statistically significant although MI trended towards significance (with the confidence interval just crossing 1)

No significant differences in cardiovascular mortality (relative risk [RR] = 0.94, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.75-1.19), all-cause mortality (RR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.89-1.14), myocardial infarction (RR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.71-1.02), and coronary artery events (RR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.65-1.11) were observed between the intervention and control groups. However, owing to limited reported cases, the impact of stroke could not be evaluated.

Besides absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.

We know that replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat, or monounsaturated fat reduces apoB.

Chat gpt critique

Here’s a refined summary and critique of the editorial “There Is More Than Meets the Label: Rethinking Saturated Fat and Cardiovascular Health” by Atsushi Mizuno (JMA Journal, published April 28, 2025; PMCID: PMC12095710) :

Summary

-

Type & Scope

This piece is an editorial, not an original research article. It reflects on the broader context and evolving perspectives regarding saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and cardiovascular health . -

Key Themes & Figures

The author emphasizes the conventional dietary advice of replacing SFAs with unsaturated fats—monounsaturated (MUFA) and polyunsaturated (PUFA)—a cornerstone in reducing cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk . A visual in the article (Figure 1) depicts this framework, outlining the lipid classification and standard nutritional recommendations . -

Broader Relevance

Keywords such as “personalized,” “genetic nutrition,” and “cardiovascular disease” signal attention to more nuanced, individualized approaches in dietary recommendations .

Critical Assessment

Strengths

-

Topical and Timely

The editorial taps into a lively ongoing debate: while SFAs have traditionally been demonized, emerging research questions blanket reduction strategies. The emphasis on dietary nuance and the broader nutrient context is both modern and necessary. -

Clear Visual

Figure 1 effectively visualizes the lipid categories and the traditional public health approach, making the argument accessible—even for a non-specialist readership. -

Balanced Tone

Although brief, the editorial avoids hyperbole—it reframes rather than dismisses established guidance, aligning with ongoing scientific reflection.

Weaknesses

-

Lack of Substantive Content

As an editorial, it inherently lacks new data, detailed analysis, or original insights. It doesn’t cite specific studies to substantiate its perspective, nor does it delve into mechanisms or evidence-grade discussions. -

Limited Depth for Scholarly Dialogue

There’s little exploration of the conflicting meta-analytical evidence. For example, umbrella reviews of RCTs and cohort studies have found that reduction in SFAs may lower risk for some cardiovascular events—but do not consistently affect cardiovascular mortality—and most of that evidence is of moderate to low certainty . -

Missed Opportunity for Personalization

Though keywords like “personalized” and “genetic nutrition” appear, the piece doesn’t elaborate on how genetic or individual differences should inform dietary recommendations in practice.

Contextual Comparison with Evidence

In the broader scientific landscape:

-

Consensus Recommendations Still Favor SFA Reduction

Major public health bodies—including the American Heart Association (AHA), European Society of Cardiology (ESC), and World Health Organization (WHO)—continue to recommend reducing SFA intake in favor of unsaturated fats for cardiovascular risk management . -

Evidence Quality Is Mixed

Systematic reviews and umbrella reviews reveal that while dietary SFA reduction can improve surrogate markers like total cholesterol and LDL-C, evidence for hard outcomes (like mortality) is less strong and sometimes inconsistent . -

Food Matrix Matters

Recent evidence suggests that the source of SFAs—whether from processed meats or dairy—could differentially impact cardiovascular risk, suggesting a food-based rather than strictly nutrient-based approach may be more informative .

Conclusion & Takeaway

- Summary: Mizuno’s editorial invites us to move beyond simplistic nutrient-label thinking regarding SFAs and to consider more holistic, personalized nutritional frameworks.

- Critique: Its brevity and lack of specifics limit its utility in guiding clinical or public health practice. It risks being viewed as thought-provoking rather than actionable.

- Recommendation: For those interested in the topic, this editorial serves best as a conversation starter. Deeper understanding requires engagement with systematic reviews and meta-analyses that weigh clinical endpoints, population heterogeneity, and food matrix implications.

@RapAdmin

Oops. I just realized I left out the link to the meta study. Here it is:

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jmaj/8/2/8_395/_pdf/-char/en

Summary of Nick’s video

Introduction to Saturated Fat and Heart Disease

- For decades, saturated fat has been labeled as detrimental to heart health, but recent discussions question this long-held belief.

- A new 2025 meta-analysis, described as one of the most rigorous studies of its kind, challenges the notion of saturated fat’s role in heart disease.

- The findings of this meta-analysis suggest that there is no supporting evidence for restricting saturated fat to prevent cardiovascular disease.

- This conclusion stands in stark contrast to existing dietary guidelines that have recommended limiting saturated fat intake to 10% of total energy since 1980.

Understanding Meta-Analysis

- A meta-analysis is a statistical method that aggregates data from various independent studies to formulate more robust conclusions about a specific topic.

- While meta-analyses are not without flaws, they can provide clarity on contentious subjects such as the impact of saturated fat on health.

- The recent meta-analysis focused exclusively on human randomized controlled trials, specifically those that examined saturated fat restriction and cardiovascular disease outcomes.

- By excluding observational studies, which are more prone to bias, the authors aimed to enhance the reliability of their findings.

- The analysis included nine randomized controlled trials with a total of 13,352 participants, ultimately finding no significant benefits from reducing saturated fat on various cardiovascular outcomes.

Interpreting the Findings

- Despite the lack of observed benefits, it is important to note that a finding of no effect does not definitively prove that no effect exists; it may simply indicate that the studies were underpowered.

- One method to reinforce conclusions is to examine whether a dose-response relationship exists, indicating that greater reductions in saturated fat might correlate with better health outcomes.

- In this case, the meta-analysis found no association between the degree of saturated fat intake reduction and any cardiovascular outcomes.

- Consequently, the evidence from human randomized control trials does not support current recommendations to reduce saturated fat intake for improving cardiovascular health.

Contradictions in Existing Literature

- Some may question why other meta-analyses yield different conclusions regarding saturated fat and heart disease.

- Different studies may have varying inclusion criteria, which can significantly affect the outcomes reported in meta-analyses.

- Previous analyses have included observational studies, which are more susceptible to bias, and may have excluded certain randomized controlled trials included in the recent meta-analysis.

- These discrepancies underline the importance of understanding the methodology behind meta-analyses and the types of studies they incorporate.

Reasons for Ongoing Debate

- The ongoing confusion surrounding saturated fat and heart disease can be attributed to several factors.

- One reason is the momentum of the status quo; scientific consensus can be slow to change, leading to resistance against new evidence that contradicts established beliefs.

- Another factor is the influence of financial interests, as various stakeholders, including food companies, may have vested interests in maintaining certain dietary guidelines.

- Additionally, the oversimplification of saturated fats as a single category fails to recognize the diverse effects different types of saturated fats have on health.

- Individual variability in response to saturated fat intake further complicates the matter, as genetics, microbiome health, and other factors can significantly influence metabolic outcomes.

Diversity Among Saturated Fats

- Saturated fats are not homogenous; they can have vastly different effects on health depending on their structure and source.

- Short-chain fatty acids, for example, are beneficial for gut health and metabolic processes, while medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) are metabolized differently and may offer unique health benefits.

- Odd-chain fatty acids, such as C-15, may also play a role in improving insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health.

- Stearic acid, another type of saturated fat, has been associated with positive effects on mitochondrial function and may not raise LDL cholesterol levels.

Individual Response to Saturated Fat Intake

- Individual responses to saturated fat consumption can vary widely, influenced by genetic factors, microbiome composition, and overall health status.

- For example, some individuals may consume high amounts of saturated fat without experiencing any significant changes in cholesterol levels.

- This highlights the importance of a personalized approach to nutrition, where individuals can track their responses to dietary changes.

- Utilizing tools like portable cholesterol analyzers can help individuals monitor their health metrics in real-time and make informed dietary decisions.

Conclusion and Future Directions

- The prevailing dietary dogma surrounding saturated fat restriction has been called into question by new evidence suggesting a lack of significant associations with cardiovascular disease outcomes.

- Not all saturated fats are metabolically equivalent, and individual responses to these fats can vary greatly, complicating public health recommendations.

- As the scientific community continues to evolve its understanding, it is crucial for dietary guidelines to reflect the most current and nuanced evidence.

- A focus on individual contexts and rigorous methodologies should take precedence over outdated assumptions regarding saturated fat.